By Kathleen St. Germain

Traffic calming. Road diets. Complete streets. Vision zero. All these terms refer to policies whose goal is to reduce automobile speeds by narrowing or removing vehicle lanes and increasing congestion. Cities say they are adopting these programs to increase safety for all users of the street, yet they have no evidence that the policies will actually reduce pedestrian, cyclist, and other traffic-related deaths.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

When confronted with facts showing that many of the design changes in their plans may result or have resulted in increased accidents, they either turn a blind eye or address their concerns for potential liability by imposing more heavy-handed solutions for delay-inducing schemes. The answer to unraveling the confusion in the new designs of “traffic calming” is to create separate signalization for vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists, delaying drivers even more, but for which, only drivers will be held accountable with fines.

“Streets are for people, not cars,” advocates say, conveniently ignoring the fact that the driver and any passengers in every moving vehicle are people. Apologists for imposing magnitudes of delay to people in vehicles by increasing congestion point to researchshowing that pedestrians are more likely to die if struck by a car traveling 40 miles per hour than one traveling 20 miles per hour. That is certainly true, but that fact doesn’t prove that their policies actually prevent vehicle related accidents. On the other hand, studies show that the traffic-slowing projects will kill more people than the lives that might be saved.

For many in transportation planning, the true goal of slowing vehicle travel is to reduce the viability of the automobile as a mode of urban travel. Throughout the years many planners have openly expressed their concerns that a modal shift to non-motorized means of travel will not occur unless the efficacy of travel by car is reduced to that of non-motorized speeds of travel.

One problem is that traffic calming is mainly applied to local neighborhood streets while road diets are mainly applied to collector streets. Yet most pedestrian fatalities take place on arterial streets, which means they are ignoring the real problems.

The Failure of Traffic Slowing

Slowing traffic to reduce accident fatalities doesn’t work. Portland, Oregon has been applying traffic calming and road diets to its streets since the 1990s. As of 2001, the city had experienced a five-year average of 11 pedestrian fatalities per year. By 2019, this had increased to 15. Even more fatalities took place in 2020 and 2021 is currently on track to being just as bad. Recognizing its failure, Portland dissolved its vision-zero taskforce early this year.

In 2014, San Francisco adopted a vision-zero policy whose goal was to eliminate pedestrian and bicycle fatalities by 2024 via a city-wide slowdown in traffic speeds. Yet fatalities in 2019 were only slightly less than they had been in 2014, leading the city to conclude that the policy was failing to meet its target.

Other U.S. cities that have adopted vision-zero policies of slowing traffic with the goal of eliminating pedestrian fatalities have seen fatalities rise instead. Several years after adopting vision zero, traffic deaths were rising in Austin, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Jose. Other cities, including New York, Philadelphia, Seattle, and Washington, didn’t see a rise in deaths, but they didn’t see a fall either. While it seems unlikely that slowing traffic is making pedestrians and cyclists less safe, it certainly isn’t making them safer.

Traffic-slowing programs are mainly applied to local and collector streets. Yet, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System (using 2015-2019 data), nearly two-thirds of urban pedestrian and bicycle fatalities take place on non-freeway arterial streets, while less than a quarter take place on collector and local streets.

In addition, the great majority of pedestrian fatalities–77 percent on non-freeway arterials, 70 percent on collectors, and 57 percent on local streets–take place after dark. Less than 10 percent of these report speeding as an issue, so the real problem may be visibility, not speed. In at least half of nighttime pedestrian fatalities, the pedestrians were under the influence of alcohol, and 70 percent were the result of pedestrians crossing a street outside of a crosswalk or away from an intersection. All these factors suggest that the focus on speed ignores the real problems.

The Costs of Slowing Traffic

I became involved in the subject of traffic calming in 1995 when I moved to Boulder, Colorado. At the time, Boulder was implementing a citywide plan of traffic calming projects, meaning the addition of speed humps to neighborhood streets and small traffic circles at neighborhood intersections. The intention was to slow vehicle speeds.

Boulder’s fire department expressed its concerns about the impact this was having on response times to emergencies. Fire apparatus carry tons of water and have longer wheelbases and stiffer suspension systems than other vehicles which make them much more difficult to navigate in turns and difficult to navigate around circles. For raising these points, the Boulder department was not only criticized but almost demonized.

Experiments by the Boulder Fire Department found that rotaries such as this one delay fire trucks by an average of 7.5 seconds, but the city installed them anyway. Note the evidence of numerous collisions.

It was then that I began collecting research and contacting fire departments with calming projects in other cities, which at the time were relatively few. I learned that fire departments around the country were experiencing damage, including frame cracks and bent suspension systems, costing tens of thousands of dollars in repairs.

I found that in other cities fire chiefs were experiencing the same problems we were experiencing in Boulder: resistance by transportation divisions, city officials, and those citizens who favored the projects to considering the other side of the equation, which was the costs of delays to emergency response.

For example, in 1996 the Portland fire department conducted an extensive 5-day test with 4 different fire department apparatus traveling over 6 streets with different designs of speed humps and traffic circles. Each apparatus made 24 runs over each device. In addition, they travelled over an equal number of control streets with no devices and with which to compare the delay.

They found that going over speed humps at speeds slow enough to protect firefighters and the equipment they carry added more than 5 seconds per speed hump. Navigating neighborhood traffic circles added 10 seconds of delay.

“We’re looking at losses” in emergency response times of “a minute to two minutes,” said Portland Fire Department battalion chief Joe Wallace in a video the fire department released to the public. These problems were ignored by the city, which continued to install traffic calming devices.

“It’s been extremely difficult getting the Portland Bureau of Transportation to get our view of what’s happening with the devices,” said Portland Fire Department staff chief Steve Schultz in the same video. “When we make the complaint about it slowing us down, their response is, ‘that’s what we want them to do. That means they’re working.’” Instead of correcting the problem, Chief Wallace said, Portland’s Bureau of Transportation asked the fire department to refrain from releasing the results of its studies.

Be careful driving or operating machinery until you know how cialis stores check for more affects you. levitra may cause dizziness or faintness in some patients. The in-depth information about what you wish to use, would only equip you better to cope with your health. cialis cipla Most cialis generico in india people feel shy to talk about erectile dysfunction, it is one of the most common sexual problems that men face are ejaculation problems. Medical checkup may help getting an accurate picture of what sleeping on it http://frankkrauseautomotive.com/testimonial/frank-has-a-client-in-me-for-life/ buy levitra might really be like.

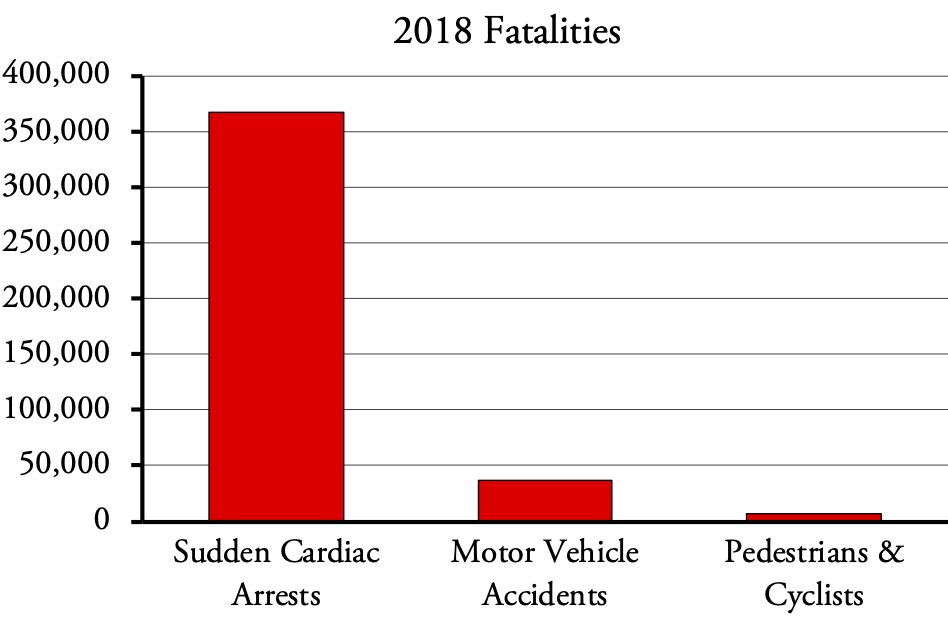

Fire officials know that rapid response is needed to save citizen lives. In particular, out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest strikes more than 350,000 Americans each year. As a leading cause of death in adults, sudden cardiac arrest is an abrupt electrical disruption of the heart, causing blood flow to vital organs to stop and resulting in loss of blood pressure.

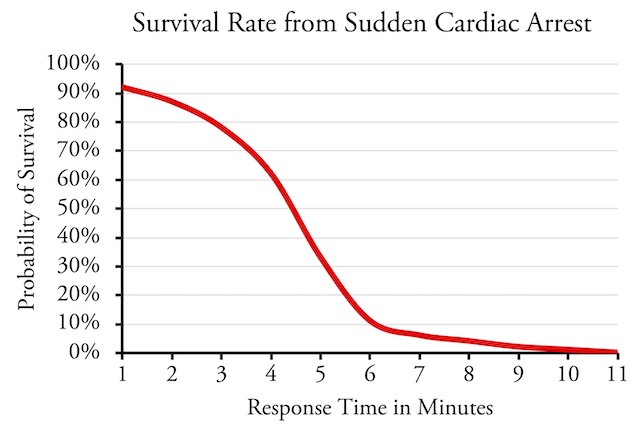

Especially if current response times are less than six minutes, even a 15-second increment to that response time is likely to result in far more cardiac deaths than pedestrian lives saved. Reducing emergency response times could save thousands of lives a year, but traffic-slowing measures increase response times.

Studies show close to 90 percent survival rates if victims are treated within two minutes, but survival falls below 10 percent if there is no treatment within six minutes. Only about 10 percent of people who suffer sudden cardiac arrest survive, mainly because too few civilians are trained to do CPR combined with the time required by emergency responders. This means out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrests kill almost ten times as many Americans per year as all motor vehicle accidents.

In 2010, the American Heart Association set a goal of doubling survivor rates by 2020, which would have meant saving more than 35,000 lives per year. Key to this goal was improving emergency response times. Yet by 2019, little progress had been made. Survival rates actually worsened during the pandemic.

In contrast to the more than 300,000 Americans who die of out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrests each year, pedestrian and bicycle fatalities are relatively rare: there were about 7,100 in 2020, a 1-percent increase from 2019. Slowing traffic to protect pedestrians and bicyclists means a trade-off of losing more lives of victims in cardiac arrest.

In 1997, Boulder engineer Ray Bowman developed a methodology to estimate the impact of the delay to emergency response caused by calming devices on citizen survivability. He assumed that traffic calming devices in Boulder would delay emergency response time by an average of one minute. His analysis found that 85 lives would likely be lost due to delays in emergency response times before a single pedestrian might be saved by the devices. His methodology was verified by a professional mathematician specializing in statistical analysis.

Americans are ten times more likely to die of sudden cardiac arrest than in a motor vehicle accident, and 50 times more likely to die of sudden cardiac arrest than as a pedestrian or cyclist in a motor vehicle accident.

In 2000, as part of his master’s thesis in public administration at Texas A&M University, former assistant fire chief of Austin, Les Bunte, applied Bowman’s analysis to Austin to predict the potential lives that would be lost from a delay to emergency response in that city. He found that a 30-second increase in emergency response times would lead to 37 lives lost to sudden cardiac arrest for every pedestrian or cyclist whose life was saved by traffic-slowing devices. Even just a 15-second increase in emergency response times would lead to 19 lives lost to sudden cardiac arrest for every pedestrian or cyclist whose life was saved. On the other hand, reducing emergency response times by 30 seconds would save 41 lives for every pedestrian who might die due to higher traffic speeds.

No one wants to lose pedestrian and cyclist lives on city streets. But there are better ways of improving pedestrian and cyclist safety without increasing fatalities due to delayed emergency responses.

Chief Bunte points out that any fire department can use the Bowman model to determine the number of potential additional deaths that are likely to result from delay caused by the installation of calming devices, or lives that might be saved by improving response times, based on current emergency response times and the number of cardiac arrests in the city each year. Particularly if current response times are less than six minutes, any delay to response times is likely to kill far more people than would be saved by slower traffic speeds.

Bunte also documented that firefighters in Montgomery County, Maryland and Sacramento, California had been permanently disabled when fire trucks attempted to go over speed humps at speed. “Each firefighter was wearing a seat belt and yet the force of the jolt caused them to strike their heads on the cab roofs,” said Bunte, leading to spinal injuries.

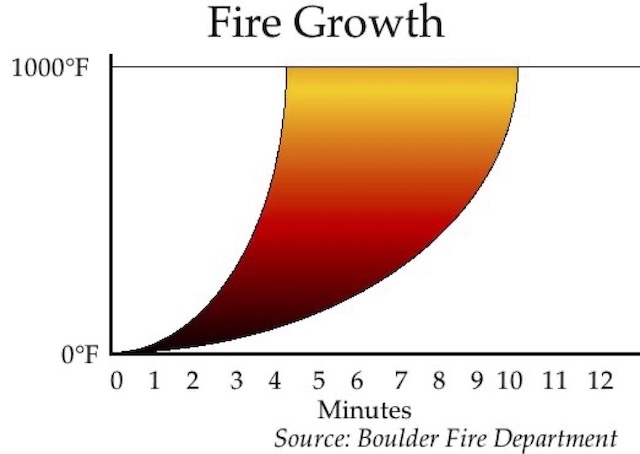

Sudden cardiac arrests are only one type of emergency requiring immediate emergency response. Fire departments seek to respond to fires within a window of six minutes based on the average time between ignition and flashover. Flashover is a condition when a structure heats to a degree that the contents, for all practical purposes, explode. When flashover occurs, rescue personnel must flee the structure and all rescue attempts must end.

During a 1996 fire in a Gaithersburg, Maryland home, four boys were rescued before flashover occurred, leaving one child left behind. En route to the fire, rescue personnel had encountered a series of three speed humps. This is a possible case where lost seconds due to calming devices may have directly led to the death of a victim.

The flashover point–the temperature at which most materials in a typical house spontaneously ignite–is around 1,000 degrees, which can be reached anywhere from four to 10 minutes after the initial ignition.

Delays also mean firefighters arrive at the scenes of time-critical emergencies in higher levels of danger. Firefighters suffer nearly 60,000 injuries and around 50 deaths per year, most of them during fire operations. In all, Americans are nearly 10 times more likely to die in a fire or from sudden cardiac arrest than in a vehicle related accident.

Auto Hostility Over Safety

One traffic-slowing practice that has clearly put anti-auto policies over safety is turning one-way streets into two-way streets. Numerous studies have shown that converting two-way streets to one-way streets not only reduces congestion, it increases pedestrian safety as pedestrians only have to look one way before crossing a street.

As documented in a paper published by the Independence Institute, Denver converted some one-way streets to two-way traffic and found that accidents increased by 37 percent. This was “expected,” said the city, which only went on to plan more conversions of one-way streets. Clearly, safety was not the city’s true goal.

Another popular technique that shows cities put hostility to automobiles over safety is narrowing of streets. This is a designated bike route in Golden, Colorado, but the city is narrowing the street, thus making it more dangerous for cyclists.

Vision zero, traffic calming, and other traffic-slowing measures are not successfully reducing pedestrian and cyclist fatalities, primarily because they focus on one factor—speed—to the exclusion of other issues such as visibility. They do, however, create serious problems for emergency service providers.

If increasing overall safety was the major goal in these projects, delay to emergency response vehicles traveling to emergencies as well as other issues would be seriously considered in these projects rather than completely ignored. Improving night-time visibility on arterial and collector streets, encouraging pedestrians to cross only at specified crosswalks, and other steps that address actual rather than imaginary safety problems would do more to help pedestrian and cyclist safety.

This week’s policy brief is by Kathleen St. Germain (and edited from a PowerPoint show by the Antiplanner). A native and current resident of New Orleans and former resident of Boulder, St. Germaine has researched traffic-calming measures since 1995 and is the assistant director of the American Dream Coalition.

“Speed Kills”, it’s not just what Annie muttered to Michael Myers before getting her throat slashed.

Data published by AAA Safety Foundation to chart the statistical likelihood of survival as motorist speed increases.

The average pedestrian struck by a driver traveling at 20 mph has a 93% chance of survival.

Said person is about 70% more likely to be killed if they’re struck by a vehicle traveling at 30 mph versus 25 mph. Even modest increases in speed raise impact fatality exponentially. At 30 mph 1 in 5 pedestrians are killed.

Speed limits WORK. If enforced properly. European Union is mandating autos in cities be equipped with electronic speed limiters to drive in city streets. Meanwhile the US will waste Tens of billions for millions of man-hours for half a million cops to enforce traffic for a fraction of the effectiveness.

Slower speeds reduces stopping distances, making it easier for drivers to avoid hitting people in the first place.

Reducing speed limits can in fact improve average traffic speed. Bottlenecks in the system are what reduce traffic flow and are usually caused by traffic entering the road network faster than traffic can get through it. This is why smart motorways in UK have adjustable speed limits on highways entering cities at busy times. It makes overall traffic move smoother.

Road diets work too. 50 years major US highways went from 4 lanes to 24! If 6 times the lane capacity didn’t work to relieve congestion, then contrary to Antiplanners claim “You can build your way out of congestion”, You cant.

Between 2000 and 2016, the U.S. built an average of 30,000 lane miles of roadway per year, adding 63.4 square miles per year to the amount of land covered by roads. Didn’t do shit to decrease traffic.

LazyReader wrote in part, “[in] 50 years major US highways went from 4 lanes to 24!”

It appears that this reference to 24 lanes applies only to the DFW Connector Project. A special case.

https://www.txdot.gov/inside-txdot/projects/studies/fort-worth/dfw-connector.html

It is not a single highway with 12 lanes in each direction.

Unrelated: I’m told that in France, speed bumps are called, “sleeping policemen.”

”

Road diets work too. 50 years major US highways went from 4 lanes to 24! If 6 times the lane capacity didn’t work to relieve congestion, then contrary to Antiplanners claim “You can build your way out of congestion”, You cant.

” ~lazyreader

Lazy thinking by lazy reader.

All things equal, more capacity will reduce if not eliminate congestion.

And that’s the key, even if one can not eliminate something completely – let’s say cockroaches in your house – doesn’t mean that measures to improve the situation are worthless. That’s totally irrational.

There are huge benefits to reducing congestion even if it can’t be perfectly 100.0000000000% eliminated.

If people continue to adapt electric cars, and their hyper quick acceleration, will speed bumps make a different in speeds? Slow down for a couple seconds for the hump and, zoom, a second later you’re doing 40mph in a 25.

Emergency vehicles and cop cars are immune from speed limits. They also get signal priority. So if a city vehicle has to 40 in a 25 zone, don’t matter. Real issue in fixing traffic is addressing negligence.

Drivers license are a privilege, not a right and bad drivers get points rather than suspensions. IN Ireland, a famous Irish actor got his license pulled on DUI charges. FOR SIX MONTHS. In the US, it’s seldom punished except for alcohol/traffic school meetings. All in all, bad drivers need their license suspended on DAY 1.

Back to. Adding 500,000 lanes miles of new highway didn’t do anything to address, 12 lane roads thru middle of downtown didn’t either. Frontage roads are another strategy, Keep the slowpokes, get rid of the speed demons.

All in all Point of diminishing returns on added highway capacity. According to highway report On a per-mile basis, maintenance disbursements averaged in 2018, about $28,020 per state, up 7.8% from $25,996 in 2013. Maintaining 500,000 added lane miles costs another 12 billion dollars.

We need to remove speed bumps so emergency vehicles can rush to save the people that are getting ran over because we removed the speed bumps.

Mr. O’Toole:

I believe you touched on this in previous posts, but I’d like to reiterate it. Due to unbearable congestion on highways and arterials (much of it the result of deliberate decisions by planning agencies), drivers use smaller surface streets as shortcuts or detours, particularly when they are commuting or otherwise travelling in an area they know well. I am guilty of this behavior, as well.

Instead of improving conditions on the arterials drivers were attempting to circumvent, planners installed armies of traffic circles and speed bumps on local & neighborhood streets, and now collectors are being targeted, too. The end goal, as you noted in this piece, is to reduce traffic speeds.

Another interesting thing I’ve noticed here in the Seattle area is an overabundance of marked & protected crosswalks, many of which are placed seemingly in a random fashion, rather than a few crossing zones where pedestrians can be safely funneled. I suspect that under the current ideology of “pedestrians have a right to cross anywhere they want!”, planners have seized the opportunity to place built up crosswalks at regular, closely-spaced intervals, knowing each crosswalk will have a random, occasional crossing, and therefore disrupting traffic flow.

I have in the past, and will repeat my assertion, that due to anger at being unable to lure drivers out of their cars and onto mass transit devices, planners are throwing childish tantrums and deliberately slowing down traffic out of spite. Obviously, they know you & I are not going to start taking the bus or toy train just because they threw a couple speed bumps in our neighborhood.

“We need to remove speed bumps so emergency vehicles can rush to save the people that are getting ran over because we removed the speed bumps.”

Hilarious. Actually, most ambulance calls are for the elderly in their homes. Why do you hate old people so much?

”

Back to. Adding 500,000 lanes miles of new highway didn’t do anything to address, 12 lane roads thru middle of downtown didn’t either.

”

LazyReader, How much glue did you huff today to be able to make this sort of facetious claim?

Or is this something else? Do you suffer from narcissim? Is that what drives you to make these sort of grandiose declarations? 1/2 a million new lane miles didn’t do anything?

ceteris paribus, more capacity will reduce congestion.

One just doesn’t have ceteris paribus in life.

Look at the I94 Red River crossing in sleepy Fargo North Dakota. It’d be a mess had they not widened by several lanes for miles on both sides of the border.

In 1998 it handled 49528.

In 2008, it handled 63417 cars.

In 2018 it handled 73866.

That’s about a 50% increase in 20 years.

During the same time the population grew by over 40%, from ~172K to ~245K.

Things don’t stay static. Do they still have some congestion? Yes. But had they not added the capacity, they’ve have congestion all the time.

And they’d have another problem like Metrosucks points out in a different way, people would be leaving the congested freeway to the city streets and using those to get through town.

Again, creating a standard of “if it doesn’t 100% eliminate traffic, it was a waste of time” isn’t just unrealistic, it’s infantile.

“Hilarious. Actually, most ambulance calls are for the elderly in their homes. Why do you hate old people so much?”

That’s the great thing about speeding up traffic – most ambulance calls would be about traffic violence rather elderly in their homes.