Three years ago, it was easy to be optimistic about the future. World poverty was in rapid decline. Many major diseases had been nearly eradicated. Global trade tied nations together, limiting military conflicts in most of the world outside of the Middle East. Thanks to good old American innovation, energy prices were low. Most environmental problems, including air and water pollution, were either solved or proven solvable. While doomsayers made dire predictions about climate change, it was hard to take them seriously when their prescriptions were the same tired old central planning ideas they had always advocated even though most of those ideas would, in fact, increase greenhouse gas emissions.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief..

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief..

Today, it is much easier to be pessimistic. The COVID-19 pandemic not only killed at least 6 million people (with perhaps a third of them in the U.S.), it revealed several critical weaknesses in the global trading system. Congress’ response to the pandemic, which was to dump trillions of dollars into the economy without increasing economic productivity, caused the worst inflation America has seen in 40 years. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is leading to both energy and food shortages around the world that are bound to get worse as the war continues. On top of this, the conflict has revived fears of nuclear war.

It is still possible to be optimistic, but improvements in world prosperity, health, and peace are not guaranteed. The United States is better insulated against military, energy, and food threats than most of the rest of the world, but it isn’t insulated against its own mistakes. In the past, increasing American productivity has overcome poor government policies, but that could change. Here are a few thoughts about how to improve the future of the world in general and the U.S. in particular.

Demography

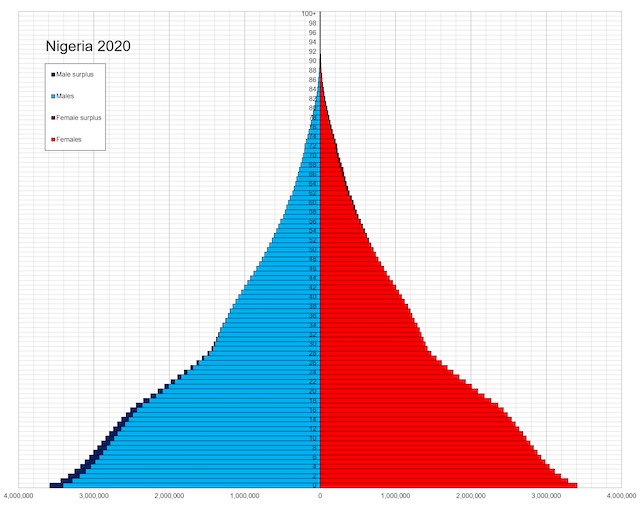

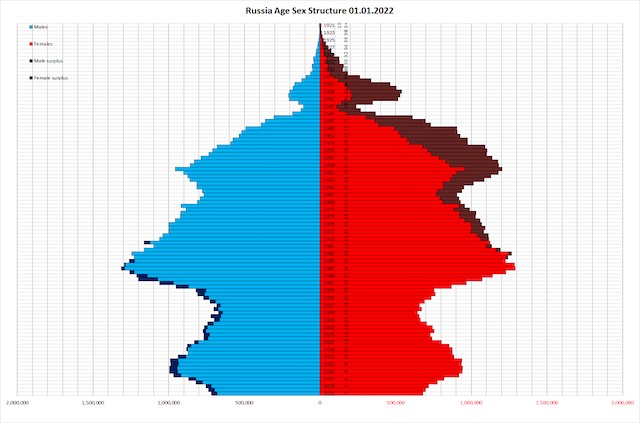

Whether due to war, economic problems, urbanization, or fears of a population bomb, the demographic structure of many countries is in trouble. Due to low birthrates, Japan and China are expected to lose half their populations by the end of the century. Russia, Italy, and many other countries also face demographic crises. While environmentalists might cheer about lower populations, aging populations face severe declines in per capita productivities that can lead to serious internal conflicts. According to geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan, one of the reasons for Russia’s low birthrate was the Communist Party’s forcing people to live in small apartments, and one of the reasons Putin chose to invade Ukraine now is because it soon won’t have enough young men to staff an army big enough to support such a military action.

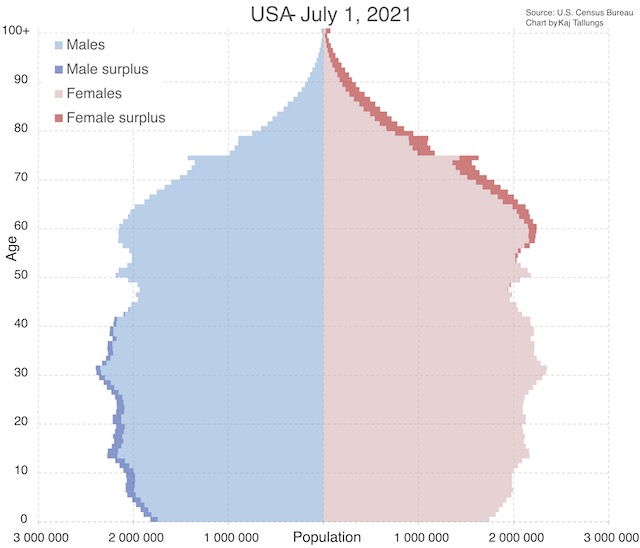

Population pyramids show the number of people by age class, with youngest ages at the bottom, males on the left, females on the right, and a darker color used for surplus of males or females. The pyramid for a developing country, in this case Nigeria, tends to be triangular. Chart by Sdgedfegw.

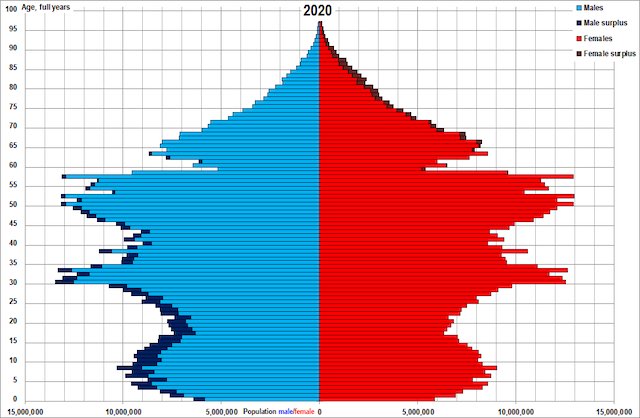

China’s one-child policy led to both a shortage of young people and a large surplus of young males. This will require a smaller number of young people to earn enough to support the entire population. Chart by Rickky1409.

Russia’s demographics are not much better than China’s. Chart by Rickky1409.

The U.S. has a better balance of age classes, partly due to large-scale immigration of young people. Chart by Kaj Tallungs

Most developing countries have young populations, and countries with aging populations could fix their demographic issues by welcoming immigration from those countries. China, Japan, and Russia, however, do not welcome immigrants.

The United States has been insulated from these issues partly because it has welcomed immigrants. Without immigration, the country would also have an aging population, though not as badly as in Japan or China. Declining immigration during the pandemic led to the nation’s slowest population growth in history.

Global Trade

The value of goods exported from one country to another has grown from under 12 percent of world GDP in 1900 to around 25 percent of a much larger GDP today. Some argue that international trade exploits people in developing countries and pushes down wage rates. In fact, what it does is increase wealth and wages in developing countries.

The modern symbol of international trade, this Chinese container ship is one of the largest in the world. Photo by Keith Skipper.

In 1960, for example, Japan’s per capita GDP was under $500 compared with $3,000 in the United States. By 1990, Japan’s per capita GDP had grown to equal and even slightly exceed that of the U.S. at $25,000 in Japan versus just $24,000 in the U.S. In 1960, Japan used its low wages to engage in international trade; by 1990, it relied instead on its technological prowess. South Korea, Taiwan, and other places that would be considered developing countries 60 years ago have similarly increased their GDPs and personal incomes.

Ideally, global trade reduces costs for importers and builds the economies of exporters. This may come at a cost of manufacturing jobs in the importing countries, but the United States and other importers have managed to maintain low unemployment rates as former factory workers move into service industries. More about this below.

Despite these benefits, there is a serious risk that the global trading system will disappear, or at least shrink. First, after seven decades of American bipartisan consensus in favor of free trade, the Trump administration started a trade war with China. This suggests that, since the United States had proven that it can be both energy and food independent of the rest of the world, many Americans were losing interest in free trade.

Second, the COVID pandemic disrupted some trade routes, but more important it led to suspicions about the good intentions of the Chinese as well as the long-term sustainability of their economic model. Finally, the war in Ukraine is disrupting important sources of both energy and food supplies.

All these disruptions will tempt many nations to become more self-sufficient and to rely less on trade even though doing so will increase consumer costs. This raises the danger that more countries will decide the path to self-sufficiency requires taking over some of their neighbor’s sovereign territory. If those countries are less involved in international trade, then nations in North America and western Europe will have less leverage to prevent such wars.

Defense

The global trading system, Zeihan points out, depended on the United States maintaining the world’s most powerful navy. For 70 years, this navy has kept sea lanes open to free trade by all nations.

Three of America’s eleven supercarriers, each of which is several times more powerful than any other carrier on the planet, are on display here. Photo by Stuart Rankin.

The United States has the world’s most powerful military partly because it spends more on defense than the next nine nations combined. This led Secretary of State Madeleine Albright to ask Colin Powell, “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?” She apparently wanted to use it for “humanitarian” purposes, such as forcing regime change in oppressive dictatorships, halting genocidal actions, and building democracy in authoritarian states.

We’ve since learned that our military is superb at ejecting an invading army from a sovereign nation, and even at demolishing an army within a nation, but it isn’t so good at ending oppression or building democracy. This led the Economist to suggest in 2011 that maybe we would be just as well off spending only half as much money on it.

Apparently, the problem is defining the mission of our military. Free trade is a worthwhile goal, but it seems likely that some of our allies, who actually benefit from free trade more than we do, could share more of the cost.

Beyond that, apparently the mission of the rest of our military is to keep potentially hostile governments in line, particularly Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. That might also be a worthwhile goal, and we might also be able to share the costs with other countries such as Japan, Saudi Arabia, and those in western Europe. However, we should give up the idea of nation-building or overthrowing oppressive dictators, no matter how heinous, as it has rarely ended well.

Food

Some people still believe that inflation is due to a physical scarcity of goods such as food or fossil fuels. In fact, inflation happens when people have more money but there are no more goods to spend it on. In the last two years, Congress has dumped several trillion dollars into the nation’s economy and yet productivity is no higher, and due to COVID may be a little lower, than before.

At the same time, the war in Ukraine has cast wheat crops in both Ukraine and Russia in doubt—in Ukraine because the war is disrupting farming and in Russia because the U.S. and other nations are attempting to boycott Russian goods. This could lead to short-term food shortages in some countries that traditionally buy from Russia and Ukraine.

America has far more farmland than it needs for domestic food production.

Fortunately, the United States has plenty of land for growing wheat and other crops and the technology for making the most of those acres. According to the Department of Agriculture, American farmers have nearly quintupled the number of bushels of wheat they can produce from an average acre of land.

The U.S. also has a large surplus of agricultural land that could be put into crop production with very little effort. More than 35 million acres of American farms are dedicated to growing corn for ethanol production, which probably has no net benefits. These acres could easily be used to grow edible corn, wheat, or other food crops. In addition, the nation has well over 100 million acres of agricultural lands now being used for pasture or range that could easily be converted to croplands. Persuading farmers to make these conversions and making this food available to other countries will require continuation and restoration of free trade routes and policies.

Class Warfare

The main objections to free trade are coming from the right, and particularly from working-class people who believe that free trade has cost them high-paying manufacturing jobs. There is some legitimacy to their complaints. At the same time, if the nation had a high level of economic mobility, then the people who worked in shuttered factories, or at least their children, could easily find jobs that paid just as well in other fields.

Unfortunately, economic mobility has seriously declined since 1970, when the nation had the lowest level of income inequality in its recorded history. Several factors have reduced economic mobility, but two of the most important are the high costs of housing and the high costs of tertiary education.

In 1970, Oregon State University charged Oregon residents $411, or about $2.200 in today’s money, for a year’s tuition. In 2022, it charged more than $12,000 a year to students taking a regular course load of 17 credits per term. Union Pacific photo.

In 1970, someone going to a state university in Oregon would pay well under $2,000 for four years of tuition—around $10,000 in today’s money. I know; I did. In some states, such as California, students would have paid even less. Today, students are lucky to find universities whose annual tuition is less than that. Such high fees are an annoyance for middle-class families but can be an absolute barrier for working-class families.

Tuition costs have grown partly because colleges have become highly inefficient and partly because states have reduced their subsidies. The standard libertarian belief is that students are the main beneficiaries of education so they should pay for it. Few of them, however, question free primary and secondary schools. The real problem, however, is that many students pay for their tertiary educations with easy-to-get loans, and the universities have responded by upping their costs to capture more of those loan monies. If only to reduce income inequality, it would be worth it for states to increase their subsidies and for students to rely less on loans and more on various work-study arrangements.

Housing, which has long been a way for working-class families to improve their economic mobility, is a similar issue. In 1970, housing was affordable everywhere in the country, even San Francisco and Honolulu. Then environmentalists pushed anti-sprawl policies, making housing impossibly expensive in most of California and Hawaii and formidably expensive in Oregon, Washington, Florida, and most northeastern United States from northern Virginia to Massachusetts. As with tuition, such high housing costs are a serious imposition on middle-class families but an absolute barrier to homeownership for working-class families.

Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, claims that income inequality is growing because returns on capital are greater than the rate of economic growth. But when MIT researcher Matthew Rognlie scrutinized Piketty’s data, he found that that housing was the only form of capital whose returns were growing faster than the rate of economic growth. Growing inequality is the direct result of land-use policies adopted by much of western Europe, most coastal states, British Columbia, Japan, New Zealand, and most of Australia.

The middle-class is a minority in this country, as only about 30 percent of voting-age Americans have college degrees. Yet they are the ones who make most of the decisions about such things as education and land-use policy. In these and other areas, including transportation, the decisions they make aim to make their lives easier even if they reduce economic mobility. Members of the working-class sense this, which was what led to the 2016 election of Donald Trump.

Economists maintain that free trade improves everyone’s lives. But economists are all middle class; their salaries have steadily grown while the costs of foreign-made clothes, furniture, and electronics have declined. While working-class families enjoyed the same low costs, many of them lost $30 a hour factory jobs and had to take $15 an hour service jobs instead, which was a net loss for them. The solution is to improve economic mobility so those working-class families can find better jobs

Infrastructure

I noted above that Japan’s per capita GDP had grown from a sixth of the U.S. in 1960 to more than the U.S. in 1990. After 1990, however, Japan’s growth slowed, so by 2019 per capita GDP in Japan was less than two-thirds of that in the United States.

The reason for that slow growth was that the government had borrowed heavily to pay for its faster growth before 1990. Such borrowings were possible because of Japan’s property bubble. Thanks to this bubble, the value of Japan’s stock market was much greater than that of the U.S. and the value of a few acres of land in downtown Tokyo was greater than all the land in California.

Japan’s first high-speed rail line reputedly made money, but political pressures led the government to construct many money-losing lines, building up debt and dragging down the entire Japanese economy. Photo by tansaisuketti.

When the bubble burst, the government responded by stepping up its borrowing, hoping to reinvigorate the economy by building more dams, highways, high-speed trains, and other infrastructure. Yet there was little demand for this new infrastructure, and so the funds borrowed to pay for it became a burden for the economy. China is currently going through the same sort of process.

When the United States had a small recession due to the pandemic, Congress imitated Japan by borrowing trillions of dollars, much of which was supposed to build infrastructure for which there is little real demand. The pandemic recession ended fairly quickly, but a new recession may begin due to inflation and other effects of Congress’ wild spending.

The problem is that politicians fail to distinguish between infrastructure that is truly productive and infrastructure that doesn’t increase the nation’s productivity. The Interstate Highway System vastly increased American mobility and productivity, but today infrastructure proponents falsely claim that any spending on any form of transportation will produce the same increase. Ironically, as pointed out in the last policy brief, many transportation advocates today object to highways precisely because they increase productivity and instead want to spend money on things like light rail and high-speed rail that promise to reduce productivity by substituting high-cost transportation for low-cost transportation.

Paying Down the National Debt

The federal debt worried people before the pandemic, but now it has reached 127 percent of GDP, which is high enough that it seriously threatens future growth and prosperity. According to the World Bank, above 77 percent of GDP, “each additional percentage point of debt costs 0.017 percentage points of annual real growth.” Members of Congress who approved this massive increase in debt believed that the United States would be immune from such problems, but the high rate of inflation we are experiencing disproves that.

Republicans and Democrats are both responsible for this massive debt. In recent years, the lowest debt (as a percent of GDP) was 31.5 percent in 2001, just as Republican George Bush took office. Before that, the lowest was 25.0 percent in 1979, just before Ronald Reagan took office.

A major problem with dealing with the debt and deficit spending is that so much of federal spending is “mandatory,” that is, obligations such as social security, Medicare, and spending out of receipts that are dedicated to certain programs (such as the Highway Trust Fund). In 2022, $4.2 trillion of federal spending was mandatory, while only $1.7 trillion was discretionary, that is, spending that Congress could easily reduce without making major changes in law. To make matters worse, 45 percent of discretionary spending is defense, which few would willingly reduce until the Russia-Ukraine war is settled.

All the money Congress spent on COVID relief and all the new spending in the infrastructure bill was discretionary. While these were supposed to be one-time-only funds, the recipients of those funds are already beating the drums to make them permanent.

A comprehensive program for fixing the national debt is beyond the scope of this paper, but a few things that can be done include:

- Encourage allied nations to share the cost of international peacekeeping;

- Reform social security and Medicare to make them less of a Ponzi scheme;

- End deficit spending on programs, such as highways, that are supposed to fund themselves;

- Review infrastructure and other programs to ensure that they truly will boost long-term productivity and don’t just transfer money to special interest groups.

Making the Right Choices

All of these issues are tied together. Spending money on national defense supports global trade which promotes food and energy security but which creates a backlash from people who lose jobs to foreign manufacturers. Spending more on infrastructure increases the federal debt making the nation less competitive in the long run.

Providing a secure and prosperous future requires making hard choices about all of these issues, many of which are often poorly understood. Immigration, for example, produces many benefits for the U.S. only one of which is saving the nation from the same demographic problems facing Japan and China. Rather than build a wall or otherwise try to enforce strict immigration laws, we should relax them.

Free trade is also worthwhile for its contributions to world peace and the improvements to the economic health of developing nations. While it comes at a cost of some manufacturing jobs in the United States, this can be overcome by dismantling the barriers to economic mobility such as anti-sprawl laws and high education costs in state colleges and universities.

National defense is important, particularly a strong navy keeping free-trade routes open to all. But the United States should urge its allies among developed nations in Europe and Asia to help shoulder more of the burden of this cost.

Food and energy security are important for world peace and prosperity. The United States should increase crop production for food, which may mean decreasing corn production for ethanol. It should also return to those policies that allowed it to approach complete energy independence in the late 2010s. At the same time, it should counter problems with greenhouse gas emissions with technological improvements in construction and transportation, not by trying to force major lifestyle changes on people, which experience shows doesn’t work.

Finally, Congress and the nation needs to avoid the mistakes made in Japan and China of thinking that all new construction is equally productive by firmly distinguishing between infrastructure that is truly productive and infrastructure that merely transfers money from taxpayers to special interests. The best way is to rely on user fees to pay for infrastructure: if a new project can pay for itself out of user fees, then almost by definition it will increase the nation’s productivity. If it can’t, then no amount of subsidies will make it worthwhile. These policies can help ensure a peaceful, prosperous future.

The biggest mistake the west ever made was handing education over to the federal government…….

For Class Warfare section I am reminded of the most recent Simpson’s episode where the former U.S Labor Secretary Robert Reich highlights

“The decline of unions, rampant corporate greed, Wall Street malfeasance and the rise of shortsighted politics all contributed to increased economic inequality, widespread real unemployment, wage stagnation, and a lower standard of living for millions of Americans.”

https://deadline.com/2022/05/the-simpsons-fox-news-tucker-carlson-1235031149/

”

All the money Congress spent on COVID relief and all the new spending in the infrastructure bill was discretionary. While these were supposed to be one-time-only funds, the recipients of those funds are already beating the drums to make them permanent.

” ~anti-planner

I suspect a lot of folks saw that one coming. The public transit community has been clamoring for more money for it’s entire existence.

Unions were always corrupt…now theyre rotten…..

unions are fine in private sector…but govt workers…..should never been allowed to unionize