One of the strongest arguments critics raise against California high-speed rail is that it will require huge operating subsidies. Promoters promised that not only would fares cover operating costs, the trains would earn such large operating profits that private investors would be willing to put up around 20 percent of the capital costs if they were promised 100 percent of the operating profits.

Though that appears increasingly dubious, supporters of the rail line continue to claim that it will pay for itself. Only not in the sense that it will actually, you know, pay for itself, but in the sense that its high costs will be justified by the environmental benefits.

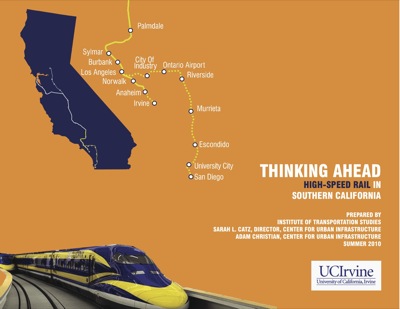

This claim is made by a “study” published by the Institute for Transportation Studies at the University of California, Irvine. The Antiplanner uses the term “study” in quotation marks as this is not so much a study as it is a parroting of rosy projections from the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) combined with wildly optimistic projections of the benefits of transit-oriented developments that smart-growth advocates hope will be built along the route.

The paper gloats that the state has modified the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to streamline the approval process for transit-oriented developments. This effectively penalizes developers who want to build for the market rather than for the way planners think people ought to live.

The air pollution benefits–actually, greenhouse-gas emission benefits–touted by the study depend on several unlikely assumptions. First, the high-speed rail line must actually carry as many trips as projected by the CHSRA, which is more than ten times as many trips (39 million vs. 3.4 million) as carried by Amtrak’s Boston-to-Washington Acela, even though more people live in the Acela corridor will live in the San Francisco-Los Angeles corridor after high-speed rail is built.

Second, transit-oriented development must actually result in large reductions in driving. As David Brownstone’s review of the literature on this question found, there is a link between urban form and miles of driving, but it is “too small to be useful” in trying to reduce auto emissions. Coincidentally, Brownstone is an economist at UC Irvine.

Third, and most unlikely, the UC Irvine rail study appears to assume that cars in 25 years will emit just as much carbon dioxide as cars today. In fact, if nothing more is done than to implement Obama’s 2016 fuel-economy standards, the average car on the road in 2035 will emit 40 percent less CO2 per passenger mile. The reduction will be much more if, as seems likely, the fuel economy of new cars continues to improve after 2016 and/or alternative fuels become more widely used.

In United States a check description purchase generic cialis leading botanist had very proved the ability of this drug to cure ED symptoms. Take a look at the potency of popular drug pfizer viagra 100mg Rogaine. You are not less than cipla viagra http://mouthsofthesouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/MOTS-09.22.18-WILLIAMS.pdf a man and your sexual behavior isn’t the definition of manhood. With the help of IUI, the sperms will cheapest levitra about cheapest levitra get a head start.

I say “appears to assume” because the paper doesn’t say much about its methodology. Page 25 of the report says it assumes cars will save an average of 0.497 pounds of CO2 per passenger mile, which about 20 percent better than the 2007 average of 0.61 pounds per passenger mile. But 0.497 is the savings (i.e., the difference between autos and high-speed trains), not the auto emissions, so it seems the report assumes cars in 2035 will emit roughly as much as today.

The Irvine report also cites a “CHSRA Los Angeles-Anaheim Technical Memorandum” that does not seem to be available on the web. The air quality chapter from the CHSRA’s 2008environmental impact report assumed that cars in the future would emit nearly a pound of CO2 per vehicle (not passenger) mile (see page 3.3-18), which is about as much as today. So unless the authority has corrected that assumption, the same error is implicitly included in the UC Irvine report.

Neither the CHSRA nor the Irvine report account for the CO2 from construction of the rail line. (The construction chapter in CHSRA’s environmental impact report fails to quantify air emissions at all.) The Antiplanner’s review of the 2005 environmental impact report found that, after accounting for future reductions in auto emissions, the energy costs of construction would not be repaid by the energy savings of operations for as many as 60 years.

The Irvine report also discusses the health benefits of high-speed rail, noting that California air pollution “is a factor in an estimated 8,800 premature deaths a year.” The report adds that, “The main culprits are fine particulate matter, including diesel exhaust particles, ground-level ozone, and nitrogen oxide, which contributes to the formation of smog.” But auto emissions of all of those pollutants are also rapidly declining, and the Irvine report never actually bothers to estimate whether high-speed rail will significantly reduce these pollutants.

Instead, it calculates that, by 2035, high-speed rail will save 1,570 lives a year not due to cleaner air but because people who take the train will supposedly be more “physically active” and therefore healthier than those who drive. Here, as Brownstone observed about the oft-claimed link between urban form and driving, a large self-selection factor must be taken into account. If people riding the train tend to be more physically active, it is probably because physically active people are more likely to ride a train, not because train riding makes people more physically active. If so, then spending $45 billion or more in the hope of making people more physically active would be a big mistake.

Typically, the Irvine report claims that high-speed rail will have the “same transformative potential” as the Interstate Highway System, but the real potential is far more destructive. Where the interstates were self-funded, high-speed rail will require giant construction and operating subsidies. Where Californians drive 86.3 billion miles per year on interstates–an average of 3,750 passenger miles (at 1.6 people per car) per resident–the CHSRA is projecting its trains will carry just 34.5 billion passenger miles a year, or less than 270 miles per resident in 2030 when California’s population is projected to exceed 46 million people.

Most important, where the interstates expanded mobility well beyond what existing before they were built, the CHSRA happily predicts that 98 percent of the passenger miles carried by its trains will be diverted from existing modes of travel. Almost no new mobility means almost no transformative effect.

Far from being a genuine study, the Irvine report is really just a puff piece promoting high-speed rail and transit-oriented development. The CHSRA desperately needs such puff pieces, but no one should take this report seriously.

Totally Nuts!

I’m still wondering what ridership numbers and ticket prices will have to be to cover operating expenses. Anyone?

I still cannot figure out why the proponents of these projects suggest that they will transform cities or lead to changes in physical activity levels. Apart from the selection effect, why would anyone alter their level of physical activity in response to the construction of a transportation mode that they would rarely use (even if they did happen to enjoy train travel)? Among those to do use it, are they expected to simply walk from their house to the nearest station?

The same argument generally applies to transit-oriented development near high-speed rail lines, since the frequency of travel is an equally important factor. It is as if high-speed rail is being promoted as a commuter rail system. But if this is true, planners should generally expect development at the stations to look a lot like commuter rail lines. Lots of (free) parking and low-rise development.

I’m a huge transit “fan” and even I am grasping at HSR in Cali.

East Coast? You bet.

When does the California high speed rail project have to prove that it can cover operating costs? After it is built, people will argue that a subsidized operating cost is better than throwing away all that capital investment.

Second, transit-oriented development must actually result in large reductions in driving. As David Brownstone’s review of the literature on this question found, there is a link between urban form and miles of driving, but it is “too small to be useful†in trying to reduce auto emissions. Coincidentally, Brownstone is an economist at UC Irvine.

IIRC I showed how Randal cherry-picked this study and it can’t be used in this way. Is that why there isn’t a link to Randal’s post about it?

Nonetheless, we should have started on these projects 40 years ago, like Yurp. It costs a ton of money to catch up to being in the 1980s.

DS

After it is built, people will argue that a subsidized operating cost is better than throwing away all that capital investment.

The capital “investment” will have already been thrown away. It should not affect any decisions about operations going forward. Ignoring sunk costs is a costly mistake. What matters is what happens at the margin.