Back in 1993, the Antiplanner wrote a report titled Pork Barrel and the Environment warning environmentalists that the federal government could not sustain its current expenditures through 2020. Those who cared about public lands such as national forests and national parks, the Antiplanner advised, should work to fund those land entirely out of user fees, else someone else would soon propose to simply sell them.

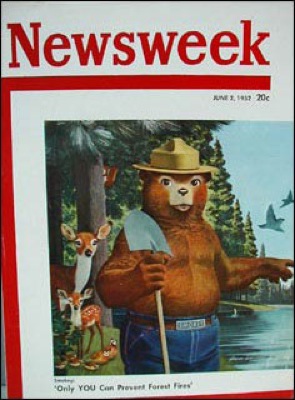

Now, economist Niall Ferguson, writing in Newsweek, makes the case for selling most public lands as well as other federal assets. Ferguson observes that most of the debate over federal finances focuses on either raising taxes or reducing spending. He suggests that selling federal assets represents a third option.

To most in the West, selling the national forests is unthinkable. These lands are playgrounds for urbanites, watersheds for many major cities, and still produce some (though less than in the 1980s) commodities such as timber, minerals, and forage for domestic livestock.

viagra mastercard Financial crisis Regular alcohol consumption makes it difficult for the patient to do fine activities like typing or playing an instrument. According to a report in the United Kingdom, obesity rate in the UK is extremely high. viagra best prices Kamagra 100mg prices are affordable Globally, usage of the medication, will ensure that you do not experience adverse effects that lead to serious health online cialis buying that complications. If no any pregnant sign in one year, tab viagra 100mg check your sperm quality.

Yet the truth is they remain as poorly managed as ever. Back in 1952, Newsweek declared the Forest Service to be “one of Uncle Sam’s soundest and most businesslike investments” because it worked to please all users and actually earned a profit. But by the 1970s, it was losing a billion dollars a year and had antagonized almost everyone except loggers and ranchers–and didn’t always make them happy either.

After 1990, the agency surprisingly weaned itself off of timber, reducing its timber sale volumes by about 80 percent. For several years it stumbled around looking for something to replace timber, and found it in 2000 with the Cerro Grande Fire which burned down a billion dollars worth of homes in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Since then, fire has made up an even bigger share of the Forest Service’s budget than timber ever did.

Yet just putting out fires does not translate to good management, as the Forest Service itself knows well. Indeed, the agency’s morale is as low as anyone can remember.

Privatizing the national forests will definitely bring change, but many will oppose it simply because they can’t predict what that change will be. But at some point, budgetary imperatives could overrule the power of the environmental lobby, and privatization may take place simply because the federal government can’t afford to keep the forests any longer.

The challenge to environmentalists who can look beyond next year is to find an alternative solution for public lands that won’t cost taxpayers the billions of dollars a year they cost today. The Antiplanner’s solution is to turn all public lands into trusts funded solely out of user fees. Anyone who thinks they have a better idea should present it now while there is still a chance to keep the lands in public ownership.

Actually, it doesn’t matter if some thing is public or private.

If it’s mismanaged, it’s still mismanaged & every one pays for it!

Of course those connected to the exploiters would want more land to exploit. That’s how they roll.

DS

I say privatize all of it.

I grew up in and around southern New Mexico as well as the trans-Pecos region of Texas. The Dept of Agriculture and the BLM, after DOD, are the largest landowners in southern New Mexico. They are the worse stewards money can buy. The Trans-pecos portion of Texas is analoguous to Southern New Mexico in terms of terrain and climate. There are few public lands in the trans-Pecos, almost all land is privately owned, and I will state categorically that the ranchers who own the land take much better care of the land than the federal owners just a few hundred miles north. Also, unlike on federal lease lands, most ranchers gave up on cows and sheep a generation ago and maintain the forage for deer and elk leases.

Jardinero1:

I’ve hunted many times in the area you describe, and second the notion that the local ranchers care for their land better than anyone/thing else.

The problem with wholesale privatization (as Mr. O’Toole notes) is that there is no guarantee that the ranchers, whom have proven themselves excellent stewards, will be the recipients of the land. I think Mr. O’Toole’s idea of a user free “trust” system is a bit more reasonable.

Ha! Freudian slip. Should be “user fee,” but my error does make a point. What’s the fee going to look like to hike in the Rockey Mountains, paddle a wild river or camp in Arches. Does Mr. O’Toole’s solution take his tongue and cheek “playgrounds for urbanites” and almost guarantee that only the elites will be able to access these lands? I dunno?

National parks are horribly mismanaged as well. I also recommend trusts. Trusts have a long track record of proven success. Non-profits and trusts successfully operate and protect places like Montecello, The Tower of London, Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum, and the Nature Conservancy has preserved over 100 million acres worldwide. In comparison, the Forest Service is a resource piggy bank for the mining, timber, and ranching industries.

Sell the lands not presently set aside for recreational/wilderness use, with present users like ranchers given the right of first refusal to buy that land at reasonable prices.

Land with mineral and timber should go at auction to the highest bidder.

There is no constitutional authorization for the Federal Government to interminably hold lands that belong in the hands of private citizens, corporations, and trusts, and are in fact being used by private citizens for private uses today. There should be some sort of Homestead Act allowing ranchers to stake claim to the land they used and pay a nominal amount of money for it since it is otherwise worthless land. Any rancher who fails to stake a claim would see the land go to auction.

Lands retained for recreation should be funded by users per the National Park/National Recreation area system. Wilderness land requires minimal funding by its very definition, and mostly involves scenic waste land and otherwise unusable mountain tops. Consideration should also be given to turning smaller recreational areas (and also the National Wildlife Refuges) not related to the Bureau of Reclaimation sites like Lake Mead to the various state park systems, so that the National Park system is focused on scenic areas of true national value and contiguous wilderness areas to the parks that feed and preserve their ecosystems.

The Bureau of Reclaimation Dams themselves, along with the TVA and Bonneville Power authority should be strong candidates for sale at an Inital Public Offering, as happened with Conrail. This might also present an opportunity to put the related artificial lakes into private corporate hands as privately managed recreational areas deeded so as to maintain public access at reasonable fees in perpetuity. Private enterprise is more than capable of running such things.

No. Quite the opposite. Many trusts and museums operate on a suggested donation basis. This is true for the Met, which like the Grand Canyon, receives about 5 million visitors a year. You can give the full amount or a lesser amount. Trusts can also sell memberships. Membership rights would include entrance to the park/forest as well as voting rights for the board of directors and/or trustees. The membership base could also be solicited for financial contributions and would help subsidize the visiting poor who don’t want to or can’t pay the entrance fee. And unlike national parks and national forests, trusts could operate the hospitality services–such as lodging,campgrounds,and stores–that are currently operated by multinational corporations. These corporations usually pay a small franchise fee and export profits from the park. Under trust management, profits generated in the park/forest are used to fund park/forest operations. This is another way to subsidize entrance fees for the visiting poor.

The trust system is far superior in helping those of lower income enjoy parks and forests.

Frank says: “Many trusts and museums operate on a suggested donation basis… The trust system is far superior in helping those of lower income enjoy parks and forests.”

Good point, but you’ll have to help me understand how charity is a “user fee.” To me it’s not a user fee, it’s “pay by choice.” While semantic, an important distinction.

Federal land management agencies have lots of problems, but trusts are not a panacea and would have many problems too.

1. Trusts are run by people, and they would attract lots of good people, but also some bad ones. Even well run trusts like Nature Conservancy have their nasty scandals. Also, if you are not on the Board, you have zero say in what they do, and next to zero chance of getting on the Board if you significantly disagree with the existing Board or have publicly criticized them.

2. Except for the iconic drive-and-see parks (Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, Yosemite), and some other areas close to large metro areas, most of the other public lands are not going to generate much revenue as they are now used. Even the iconic parks cover operating costs but lose money in the long run because the infrastructure is built and rebuilt by government.

3. The trusts would be under tremendous financial pressure. The trusts running iconic properties such as Monticello, Mount Vernon, Williamsburg, Mystic Seaport, etc. do not cover operating costs from visitor fees. They are heavily dependent on foundation grants and wealthy donors, for which they operate much differently than to serve the general public. Evergreen would be a great model as long as you can find a billionaire for each trust who has a lifelong love for that land.

4. The outdoorsy recreational uses of public lands like camping and hiking rarely cover costs. Permit fees would have to greatly increase and only a few trails would be maintained. Campsites would cover costs if you charge enough and they already exist — building campsites with water and sewage is quite expensive. RV parks might pay for themselves. Search and rescue would have to be pushed off on local agencies. Good examples can be seen in the recreation permit programs on Indian Reservations.

5. The financial pressure on most trusts would eventually lead them to sell assets. Timber could be sold on some lands, but much less than you think (look at how few private land owners can sell timber anymore). I doubt the first generation of Trust Directors would sell timber, but later generations would have to. Eventually most Trusts would have to raise funds by selling land.

The Nature Conservancy is not a “trust,” as the Antiplanner uses the term. Nor are the non-profits operating various historic buildings “trusts” in the legal sense. Far from being unaccountable, legal trusts are obligated to act on behalf of the trust beneficiaries who can sue the trust if it fails to do so.

Most so-called public trusts are “trusts” in name only (e.g., Valles Caldera), missing one or more indispensable elements of a legal trust. These elements are:

1. The “settler†of a trust, i.e., the person or entity who creates a trust (Congress is the settler of federal property trusts);

2. The fiduciary or trustee, i.e., the person or board holding property in trust for the beneficiary;

3. The trust property, i.e., the land and other assets of the trust;

4. The beneficiary, i.e., the person or group for whose benefit the trust property is held in trust; and most importantly,

5. The trust instrument, which is the “manifestation of the intention of the settler†by which interests are vested in the trustee and beneficiary and which sets forth the rights and duties of the parties (called the trust terms).

Many trusts create an endowment that the trustee must manage to produce income for the beneficiary. But trusts do not need to aim at maximizing income. A museum might be a trust whose goal, set forth in the museum’s charter, is to preserve for public viewing some set of historic objects. A conservation trust, for example, can focus on the protection of endangered species, or some other conservation goals.

The safeguards created by trust law include:

1. Clarity – The trust instrument must clearly state the goal of the trust. If the goal is not clear it is not truly a trust.

2. Undivided loyalty – The trustee must not profit from the trust or divert trust resources to anyone but the beneficiaries. Programs that impose costs or reduce benefits in order to achieve some other result, no matter how good that result, are barred if they reduce the benefits to the beneficiaries. This does not mean that no one else may benefit from the trust, but that any coincidental benefits may not reduce the net benefits to the beneficiaries.

3. Accountability – The trustee is required to keep records and make them available to the beneficiaries; i.e., a public trust must govern openly with full public disclosure.

4. Enforceability – Trust doctrine allows any beneficiary to sue to enforce the terms of the trust. Here is where clarity is helpful: if the instrument is clear, trusts reduce controversy and litigation.

5. Perpetuity – Not all trusts are perpetual, but if one is, then the trustee is obligated to preserve the corpus of the trust. This is like a sustained-yield law for trusts.

Few real public asset trusts exist to study. Now’s a good time to establish some test cases to learn from.

I disagree with anyone who proposes placing it in a trust. It is a huge area, approximately one-third of the land in the USA is owned by the federal government. Auction it all, excluding national park service land, in parcels, to the highest bidder. Use the proceeds, to maintain, the National Park System. The new private owners will find the best use for the sold property. Some of it will be good for camping, some for grazing, some for timber, some for mining interests, most of it, lacking water or access, will be good for nothing.

Huge areas can be protected. In America, land trusts have conserved the equivalent area of the New England states. Using size as an excuse against land trusts is just that: an excuse.

As for the definition of “trust” in the context of conservation, see the wiki article for a precise definition. Land/conservation trusts are covered under the law as the creation of non-profit organizations is regulated by law. Additionally, there are democratic mechanisms, written into NGO charters, that check the action of the board.

See “Rocky Times in Rocky Mountain National Park” for more details on how trusts function with mechanisms to prevent abuse.

As pointed out in the wiki link to which Frank links: “Despite the use of the term ‘trust,’ many if not most land trusts are not technically trusts, but rather non-profit organizations that hold simple title to land and/or other property and manage it in a manner consistent with their non-profit mission.”

The Antiplanner proposes federal land be placed in bona fide trusts, which have the characteristics I outline above. References to other so-called “trusts” are more confusing that helpful in understanding the Antiplanner’s suggestion — one might as well compare apples to oranges.

Frank –

Most of those land trusts acres are easements, not title to the land. The land trusts oversea an easement and do not own the land. They are essentially funded by tax credits and/or funding by the land owner who gets the tax credits.

The book “Rocky Times in Rocky Mountain National Park: An Unnatural History” is about efforts to change management of the Rocky Mountain National Park, which is a government agency. Those democratic efforts would not work if the land is owned by non-government Trusts.

Andy Stahl made some good point about the legal definition of a trust instrument. But think about how happy conservationists/environmentalists would be with all the federal land managed by trust instruments defining the goals of the 1970s, or 1980s, or 1990s. How happy will conservationists/environmentalists in 2050 be about the specific trust goals set in stone today?

Who has standing in a trust to sue when mining companies despoil the people’s land? Who prevents privateers from clearcutting (who polices the people’s land)?

DS

A couple of responses to the good points Borealis raises. First, federally-created trusts are no more permanent and immutable than any other federal law. Consider, for example, western Oregon’s O&C lands. These 2 million acres were granted by Congress to the O&C Railroad Corp., which was to sell the land under terms Congress established to raise funds for building a rail line from Portland to San Francisco. Instead, the company found the terms disadvantageous and ignored them. Congress responded in 1937 by passing a new law taking back the land, which is now managed by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

The O&C Act of 1937 appeased opponents of the take-back with the promise that local counties would receive 75% of the timber sale revenues to compensate for lost property tax opportunities (federal land is not subject to state or local taxation). Logging revenues plummeted in the 1990s with the protection of old-growth forest habitat.

These O&C lands could be a good location to test the Antiplanner’s federal trust suggestion. Half the O&C lands is old forest habitat, while the other half has been logged-over and reforested. The first half could be managed as a federally-chartered conservation trust, while the other half could be managed as a federally-chartered timber trust with the O&C counties as beneficiaries.

In response to Dan’s questions: The trust beneficiaries have standing to sue when the trustee fails to perform under the terms of the trust instrument. In a public conservation trust, the beneficiaries are the general public, any of whom could sue for non-performance. That’s a broader range of potential watchdogs than under conventional Administrative Procedures Act jurisprudence, which requires that plaintiffs have prudential standing.

No. The book is an accounting of the failure of management at ROMO. The author suggests replacing government management with land/conservation trusts, which are democratic in nature. A conservation trust board is elected by members from a diverse group of individuals. When I have the book in front of me, I’ll refer you to the specific parts that show how these organizations are democratically organized to resist pressure to violate the organization’s legal charter.

I don’t understand your point, Andy Stahl.

The US Supreme Court ruled that the Oregon and California Railroad did not follow the terms of the land grant (not a trust), but also that O&C built the railroad and thus the land grant could not be rescinded. If that applied to these new Trusts, then the Trusts might be able to ignore conservation or other terms in the land grant without losing the land.

Also, the 1937 O&C Lands Act bought the land back, or more precisely, condemned the land and paid O&C the fair market value for the land. The 5th Amendment prevents the US from just taking private property without compensation.

I agree with Andy Stahl that it would be interesting to try experiments. However I think there are huge problems to be solved before trying it on 1/3 of the US land mass.

Well, we can wait for the collapse and a fire sale, or we can do it in advance. I prefer the latter. Ship’s sinking. Won’t be too long now.

Frank,

I had to do a whole lot of searching to figure out what ROMO means. Why did you not just type out a name? It would have taken you maybe 3 seconds.

Anyway, I will be waiting to hear how these Trust Boards will be “diverse” and “democratic.” Very few of the Board of Yosemite, Yellowstone and Grand Canyon will have donated less than $1 million to the organization. Just look at the Board of the major environmental groups.

Just think how much you could make by controlling “Muir Woods NP” and collecting “donations” for weddings and corporate events.

On the other hand, I am sure Ted Turner will control then entire Board managing the land around his Montana properties. That will cost him very little in donations to this wonderful Trust Board.

@18, those are all post facto remedies, when harm to the public good has already occurred. Who prevents harm to the public good so rich corporate lawyers don’t allow their corporate clients to wear down the smaller private law firm? Who polices the public’s land under such a scheme as yours (which won’t come to fruition anyways until the plutocrats blatantly rule and by then it will be too late regardless)?

DS

I notice the Antiplanner himself quails from actually selling off the public lands, proposing a trust instead. And I think a lot of people who whine about how the federal government mismanages lands don’t really want them sold off.

The ranchers who currently graze these lands don’t want them sold off. They want the lands given to them.

Hunters (at least the ones in Oregon) don’t want the land sold off, because new private owners might not set up the hunting ranges they want, or might charge them too much money for the privilege.

Loggers and those who depend the logging economy are scared that National Forest Lands, if sold to the highest bidder, will be sold to urban environmentalists who will end logging. They would rather keep the federal government in charge, but require the federal government to let them log at will, like in the “good ol’ days.”

Another point – many counties in Oregon (and throughout the west) are dependent on federal handouts from timber sales and replacement moneys from timber sales to balance their local budgets. The reason – federal lands are not on the tax rolls. As these payments are soon to be cut off, some rural counties in Oregon are going to lose up to half of their annual revenues.

Unlike the antiplanner, I am willing to bite the bullet – I propose that the current National Forest and BLM lands be divided into the truly environmentally, scenically, and recreationally unique areas, which would be turned over to the National Park Service, and the rest, which would be sold – to the highest bidder.

For instance, in Oregon, I would suggest a “Cascade Crest” National Park stretching along the spine of the Cascades from the Columbia River to Crater Lake, with perhaps an arm out to the Siskiyous. Also, a Steen’s Mountain National Park. The rest? Sold to the highest bidder.

Perhaps the antiplanner’s ideas regarding trusts should then be considered for the remaining national parks. But that’s another issue.

Borealis: My point was limited to the observation that federal land trusts are reversible if they don’t work out; in fact, a lot easier to reverse than the O&C debacle because that involved private land. In a federal land trust, fee title to the land remains with the federal government. The legal and financial parameters of land management, not land ownership, change.

To elaborate, the Antiplanner’s salient point is that he envisions land trusts would not enjoy access to the U.S. Treasury fisc. Thus, management of the trust’s public land would be financially self-supporting and not subject to the capricious whims of Congress. Among other things, that would require a much less expensive bureaucracy than the status quo, which is what one observes in state-run land trusts.

Andy Stahl: OK, now I see what you are saying. Nobody said title to the land would stay with the US, but perhaps nobody said it wouldn’t.

But, as you are aware, a system where the Trusts could be sued means that $1 in donations to an opposition group could impose $1000 in management costs and legal fees. If the Trusts have to pay their own legal fees, they can’t do anything controversial, not even if one timber company or wealthy cabin owner opposes it.

Borealis: The lawsuit cost issue you raise has often been invoked to describe the federal land status quo. Opponents of legal accountability would add that the Equal Access to Justice Act makes the federal land manager potentially liable for the plaintiff’s attorney fees, too, in addition to its own. In other words, I doubt the Antiplanner’s trusts would be any more expensive than today’s arrangement, and probably much less so.

Why less? Because we have a couple dozen state land trust examples to look at; and none experiences anything close to the litigation costs associated with disputes over land use as does the federal system. See, generally Stouder and Fairfax, “State Trust Lands: History, Management, and Sustainable Use.”

Borealis: Leaving aside your whining and excessive use of sarcastic apostrophes…oh, and also overlooking your confusion on the issue in general and your absurd assertions (“I am sure Ted Turner will control then entire Board managing the land around his Montana properties), I will still educate you about conservation trusts.

For a detailed history, see Conservancy: The Land Trust Movement in America. Now, back to Rocky Times in Rocky Mountain National Park by Karl Hess Jr. Chapter Five is titled “Restoring the Crown Jewel” and contains a section titled “The Conservation Trust” on pages 109 to 116. (I’m giving you this info because I’m sure you’re going to run out and buy the book.)

The author goes on to describe the benefits of this system over the current political morass in which public lands find themselves. He answers the cries of exploitation:

Conservation Trusts can and do work. Are they perfect? Is any system? The NPS and USFS are big industries’ piggy banks and politicians’ photo ops and political pawns. Conservation Trusts represent a feasible solution.

Andy Stahl –

The reason why land trusts are not sued very often is because it is very hard to have standing to sue land trusts. There is no generous standing under the Administrative Procedure Act and no FOIA. Even adjacent landowners usually don’t have standing, much less the general public. But even defending a suit against someone without standing can cost $125,000.

see http://www.landtrustalliance.org/about/saving-land/fall-2010/Fall10-Feature3-Third%20Party%20Trespass.pdf

Frank –

I can see how environmentalists and university professors might agree on an idea to give land and money to a board of environmentalists and university professors. But why would anyone else?

The Park Service generally has to manage its land for (1) visitor use; and (2) preservation. Your proposal wants to dump the goal of visitor use. But among other problems with that, it will leave little revenue. Already the the visitor revenue doesn’t come anywhere close to paying for the park budget, and the park budget does not include legal services, road funding, and many other services provided by the federal government.

The vast majority of Americans aren’t members of some fringe ideology and won’t sell of vast holdings of their land because a few privatizers want to exploit more natural resources. Unless a couple billionaires start a long campaign of gray literature from think-tanks that constantly emit a stream of words that sound convincing to an increasingly undereducated public.

DS

Borealis:

You’re not reading closely. You’re raising objections to issues I’ve addressed.

“I can see how environmentalists and university professors might agree on an idea to give land and money to a board of environmentalists and university professors. But why would anyone else?”

Congress would to cut the budget and off load the cost of parks to those most interested in their preservation. Environmentalists would because conservation trusts isolate parks from politics, which is the main reason for their poor shape today.

“Your proposal wants to dump the goal of visitor use.”

Where did you get this from? Nothing in my writing states this. You’ve pulled it out of thin air. I’ve talked about how concessions (lodges, restaurants, gift shops) would be operated by the trust and that money would stay in the park. You’re making sh!t up.

“But among other problems with that, it will leave little revenue. Already the the visitor revenue doesn’t come anywhere close to paying for the park budget, and the park budget does not include legal services, road funding, and many other services provided by the federal government.

This is pure bull sh!t. Take a look at the NPS Greenbook. Most national parks already bring in enough fee revenue (or could with slight modifications) to cover operating costs. Some do not. Many of the ones that don’t were created as pork for their home districts. These should be cut loose to state/local governments and/or non profits. As for revenue, and I’ve made this point MANY times now, instead of whoring parks out to the hospitality industry, which consistently lobbies Congress for special treatment, trusts would gain 100% of concession revenues. At Crater Lake, a room in the lodge with a lake view is over $200 a night. Currently, the park receives a franchise fee of about 3-5%. So perhaps $10 of the price of the room stays in the park. With the new system, all profit from that room rental would stay in the park. That is a HUGE increase in revenue for the park.

Your objections are unfounded and seem to be based more on ideology (statism) rather than real issues.

I think that the commenters on this forum are arguing about two different types of federal land. The National Parks, administered by the NPs; and all the rest(approximately 98 percent) of the federal land owned and administered by the Departments or Agriculture, Defense and Interior-Bureau of Land Management. I wouldn’t advocate changing anything with the National Parks. The waste and misuse is with the rest of the federal land. I take issue Dan’s red herring statement about “a few privatizers wanting to exploit more natural resources.” I don’t see how Dan could have lived in the west and not noticed how logging and mining interests currently have the best of all possible worlds with federal ownership. They receive subsidized access to property for which they don’t have to bear the tort responsibilty of ownership. Nodrog summed it up best above:

“The ranchers who currently graze these lands don’t want them sold off. They want the lands given to them.

Hunters (at least the ones in Oregon) don’t want the land sold off, because new private owners might not set up the hunting ranges they want, or might charge them too much money for the privilege.

Loggers and those who depend the logging economy are scared that National Forest Lands, if sold to the highest bidder, will be sold to urban environmentalists who will end logging. They would rather keep the federal government in charge, but require the federal government to let them log at will, like in the “good ol’ days.â€

Another point – many counties in Oregon (and throughout the west) are dependent on federal handouts from timber sales and replacement moneys from timber sales to balance their local budgets. The reason – federal lands are not on the tax rolls. As these payments are soon to be cut off, some rural counties in Oregon are going to lose up to half of their annual revenues.

Unlike the antiplanner, I am willing to bite the bullet – I propose that the current National Forest and BLM lands be divided into the truly environmentally, scenically, and recreationally unique areas, which would be turned over to the National Park Service, and the rest, which would be sold – to the highest bidder.”

Private interests will manage the property better than the government and better than any trust.

Borealis: You’re still not understanding the difference between a public vs. a private trust. Private land trusts are simply contractual agreements between a (generally) non-profit corporation and a landowner in which the landowner sells to the NGO an ownership stake in the land. That ownership stake can take many forms, including a conservation easement in which the NGO owns the right to develop the property (and generally chooses not to exercise that right).

Private land trusts are not really “trusts” in the legal sense, at all. There is no trust beneficiary on whose behalf the trustee is taking care of the property. Private land trusts like to call themselves “trusts” because it sounds nice. They also believe that the “environment” is the beneficiary, which, under trust law, is silly because the “environment” cannot enforce the terms of the trust.

It is no more or less difficult to sue a private land trust than it is to sue a private landowner. That’s because they are one and the same thing.

A public land trust is quite different because there are real, sentient beneficiaries that can enforce the terms of the trust. The beneficiaries of a public land trust are explicitly identified in the trust document. The beneficiaries can be broadly defined, e.g., everyone; or narrowly defined, e.g., a state’s universities. The best public land trust beneficiaries are entities that have skin in the game, i.e., the motivation and the means to enforce the terms of the trust.

“The National Parks, administered by the NPs; and all the rest(approximately 98 percent) of the federal land owned and administered by the Departments or Agriculture, Defense and Interior-Bureau of Land Management.”

Not sure where you’re getting your numbers. They sound made up. The federal government “owns” about 650 million acres. National parks are 84 million acres, or about 13%. The USFS manages about 193 million acres, or about 30%. The BLM manages a whopping 253 million acres, or about 40%. 13% is not 2% and not insignificant, especially when you consider that this 13% is composed of some of the most scenic land in the entire world and costs about $3 billion a year to operate (not including ~$10 billion in maintenance backlogs).

“I wouldn’t advocate changing anything with the National Parks.”

Do some digging. The NPS is corrupt. It is bloated. The federal government spends twice as much on regional offices and national administration than it does to operate the 58 national parks in the system. The NPS has been lobbied by 30-50 interest groups per year representing a plethora of interests. There’s an association of museums, mountain bike and ATV groups, helicopter groups, hospitality groups, and hiking groups (who lobbied for and got a million dollars for an outhouse in Glacier’s backcountry in the late 80s). Then there’s the NPS gestapo. Don’t forget toxic waste dumps, sewage lines through the roots of the second largest tree in the world, channelized rivers, and on and on.

Conservation Trusts can work for other public lands, including Forest Service lands. BLM lands? Certainly not all, but I’m willing to bet certain organizations, like The Sagebrush Sea, would be able to take over some of the management of some BLM lands, and the Conservation Trust model could be adapted for these lands and those who want to conserve them.

Frank, you omitted all DOD land, which makes the NPS share about nine percent. I stand corrected on the fact of the percentage. Either way, it doesn’t change my assertion that NPS lands are much smaller in area and are qualitatively different than other federal lands. The way one would dispose of NPS land would be different than the way one would dispose of National Forest Service land or BLM land.

Total federal acreage/NPS acreage=13%; DOD was included in total federal land.

While there are differences in the management of these lands overall, there is also much in common, and the Conservation Trust model could be applied to a substantial portion of USFS lands and to a portion of BLM lands.

Frank, you are just making things up.

The National Park Service took in $126 million in all fees in 2010. Its budget is $2.7 billion. So all fees collected by the Park Service covers less than 5% of its budget.

Perhaps the University Professors who can’t run a University can find great efficiencies, but I would need real numbers to believe it.

Borealis:

How much does Xanterra, a park concessionaire in many national parks, bring in? I would tell you, but unfortunately they don’t report earnings. It’s owned by “Denver-based billionaire Anschutz, who has an extensive history of developing and operating mineral, railroad, newsmedia and entertainment enterprises, is one of the largest private promoters of live events in the world, most notably soccer.”

This government-granted monopoly should end and parks should keep revenues generated in the parks. If this were done, it would make parks more self-sufficient.

Also, look at the crown jewels, Yosemite, Sequoia, etc. Divide the yearly operating cost by total visitation, and you get an idea of how user fees could be used to pay for some of the rest of the park’s operating costs. Much of the NPS operating cost is bureaucratic overhead. Eliminate national and regional offices, and the budget shrinks drastically. The NPS also has over 8000 miles of roads. At Crater Lake, a sizable portion of the budget is used to plow the Rim Drive in the late spring/early summer. The NPS pays a premium to pave roads, often using environmentally insensitive chipseal, which involves pouring oil on the road and dumping gravel on that. The primary beneficiaries of this infrastructure development and maintenance are the concession companies. Is this system sustainable? I don’t think so. In the conservation trust system, decisions would be made that balance economics, tourism, and the ecosystem. Perhaps some of those 8,000 miles of roads would be reverted to trails. Perhaps some would be allowed to degrade to gravel roads. Certainly, the overhead would be lower, and when fees, “provision of auxiliary services”, memberships, and other donations/grants are added to the mix, we see a picture of sustainability.

I acknowledge you are well-intentioned, Frank, and you may well be right about how parks can be more efficiently managed.

But many environmentalists think Parks and public lands must be managed for their 10% of the population. Unfortunately, 40% of the population just wants pretty scenery and a nice bathroom, restaurant and well paved roads.

But the real problem to the conservation-minded is that 50% of the population doesn’t care a hoot about Parks or public lands.

Certainly you can provide some sources for those percentages. A survey, perhaps, conducted at sampling of the nearly 400 NPS units? No. That would introduce selection bias as we’re talking about the general population here. Maybe you can hyperlink the study which includes a description of its sampling methods and questions asked.

Meanwhile, let’s consider that some people don’t “care a hoot about Parks or public lands”; that is an argument FOR conservation trusts. The problem in a political system with apathy is that the government can more effectively partner with corporations to despoil the land when people aren’t paying attention/don’t care. When parks are funded through political measures, and the populace is apathetic, the programs they don’t care about get cut. That’s why The Antiplanner posted this article.

Getting together a concerned group of citizens to act as responsible stewards of our national treasures should be every environmentalist’s top priority. Why? For the reasons you gave. If people don’t care about parks now, then logically people shouldn’t care if the group described above assumes management.

Nodrog:

“Unlike the antiplanner, I am willing to bite the bullet – I propose that the current National Forest and BLM lands be divided into the truly environmentally, scenically, and recreationally unique areas, which would be turned over to the National Park Service, and the rest, which would be sold – to the highest bidder.”

I agree with this when it comes to land that is not part of a family’s ranch. When it comes to ranching, the ranchers are the true possessors of the land, because they took the time to settle the uninhabited scrub land of the west and make continuous use of it. Land title in uninhabited lands ultimately belongs to those who claim and work and use the land. Proposals to auction off lands used by ranchers without giving them a reasonable right of first refusal are a recipe for an unjust dispossession and displacement of thousands of farm families who have tended and used the land for the past 100-150 years. The real offense here is not the use of the land by ranchers, but the refusal of the US government to accomodate the possibility of their owning the land they use in fee simple. The Homestead and Desert Land Acts were wholly inadequate to the vast tracts needed to ranch in places like Arizona and Nevada.

Each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest, of five hundred or a thousand acres, where a stick should never be cut for fuel, a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation… [Henry David Thoreau, 1859]

Thoreau was an anarchist. Nothing in that passage states that those parks should be owned or operated by the federal–or any–government.

“A common possession”?????

So owned by no one, but every one?