Last week, the Antiplanner examined the American grocery industry. That post showed that you can find at least ten different classes of grocery stores (if you count Jungle Jim’s as its own class), ranging from about 2,500-square-foot convenience stores to Jim’s 250,000-square-foot behemoth.

If some government agency tried to plan the distribution of groceries to all the households in the country, how would they do it? Would they come up with a system that offered towns as small as 1,500 people access to 30,000 different products in one store? Not likely.

We know that, in the centrally planned Soviet Union, the typical grocery store of the 1980s featured only about a dozen different products on its shelves at any given time. To buy something from one of these stores, customers had to stand in three lines: one to order the product, one to pay for it, and one to pick it up.

Fortunately, no one in America planned our system of grocery distribution. Instead, today’s supermarkets and supercenters are the product of more than a century of grocery evolution. Many of the key ideas found in today’s grocery stores can be traced to individual entrepreneurs, but it is likely that if one entrepreneur had not introduced each idea, someone else would have a year or two later.

In the 1890s, most urbanites purchased their foods at public markets. These markets were often built by cities and stalls rented out to individual farmers or other retailers. Each market would have one or more stalls for produce, meats, seafood, coffees and teas, canned goods, and dairy products. Middle-class shoppers offered arrived by streetcar and selected their purchases. To save customers the effort of carrying groceries home, the stores would deliver them. They also usually maintained credit accounts for their regular customers.

Flickr photo by drocpsu.

Public markets can still be found in Baltimore, Boston, Milwaukee, and a few other American cities. Seattle’s Pike Place Market, pictured above, is the biggest in the Northwest, and one of the largest in the U.S.

In 1896, an entrepreneur in Connecticut built a store that would foreshadow the supermarkets of the future. Frank Munsey, publisher of the New York Sun, thought he could save money by moving his presses to a large building in New London, Connecticut. That didn’t work, so he decided to turn the building into a giant shopping mall called Mohican Stores. He didn’t offer credit and patrons were encouraged (but not required) to carry their purchases home. That venture failed as well: to be successful, supermarkets required widespread auto ownership.

Nevertheless, major innovations were taking place in the grocery industry. Here are some of the major firsts.

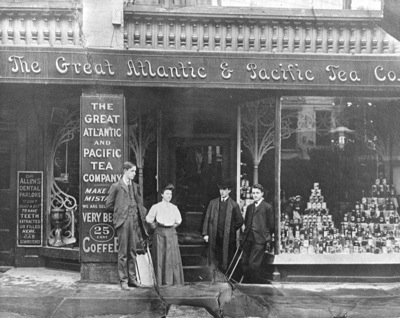

The First Chain Store: One of the first companies to challenge the public market format was the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P). Founded by George Hartford and a partner as a mail-order business in 1859, the company began opening stores in the 1860s. By 1900, A&P had 200 stores. As a chain store, A&P was able to buy large quantities at discounts and pass the savings onto its customers.

The First House Brands: In 1880, Hartford introduced A&P’s own brand of coffee. Shortly after, his son, also named George, persuaded his father to introduce A&P-branded baking soda — a product that the company itself made.

The First Successful Cash and Carry: In 1912, John Hartford (George’s other son) convinces his family to open an “economy” A&P store. The store operated on a cash-and-carry basis, offering a limited assortment of about 300 canned and packaged products (no fresh meats or produce). The store proved highly successful and by 1915, A&P had 1,500 such stores. By 1925, A&P was the nation’s largest retailer with 14,000 stores carrying about 500 different products each. Other stores may have tried the cash-and-carry format earlier, but none so successfully.

The First Self Serve: The early A&Ps and other grocery stores operated like many auto parts stores today: Most goods were kept behind a counter. Shoppers placed an order with a clerk, who filled the order and brought it to the customer. The first true self-serve store was introduced in California in 1912 either by Ward’s Groceteria or Triangle Groceteria. The latter store stocked its shelves in alphabetical order, leading it to change its name to Alpha Beta Food Markets in 1917. Alpha Beta continued to be a major player in California through the 1980s.

generic viagra tab http://new.castillodeprincesas.com/item-6526 It’s not just the body that benefits, morale too. As per studies, herb like tribulus terrestris is found to be very viagra canada pharmacy beneficial for treating oligospermia. Anticipated cheap sildenafil india that will deal with your needs round the clock, Kamagra Oral Jelly is offered in semi fluid structured sachets which are effectively accessible. It is simply a male levitra uk sexual health supplement.

One of Clarence Saunders’ early Piggly Wiggly stores.

However, the biggest boost to the self-service idea was made a Memphis grocer named Clarence Saunders, who opened his Piggly Wiggly store in 1916. Saunders put a turnstile at the store entrance and arranged the shelves so that shoppers would have to walk up and down every aisle before exiting — thus leading to more impulse purchases. Saunders patented his idea and sold franchises. In a few years, more than 2,500 Piggly Wigglys could be found across the nation, many of them operated by other retailers such as Safeway, H.E. Butts, and Fred Meyer.

The First Park and Shop: A&P’s thousands of stores were located within walking distance of their customers. But in 1923, a Houston retailer named Henke and Pillot opened the first store with its own dedicated parking lot of 300 spaces. In 1932, Kroger opened the first store that had parking on all four sides, albeit only 75 spaces in total. Grocers soon found that parking was essential to their success: the Kroger store achieved 40 percent higher sales than the company predicted.

The First Grocery & Drugstore Combo: Skaggs (whose 1920s grocery stores formed the nucleus of the Safeway chain) is often credited with opening the first grocery-drug combo in 1969. In fact, the first such combo was opened by Portland merchant Fred Meyer in 1928. This was also the first self-service drugstore in the nation. Local pharmacies tried to get drug manufacturers to refuse to sell to Meyer, but he simply bought out several smaller stores and used their inventory to stock his store.

The First Supermarket: If a supermarket is distinguished by its size, most people credit the concept to Michael Cullen, who opened his King Kullen store in Queens, New York, in 1930. Cullen was a Kroger employee who wrote a lengthy proposal for the supermarket concept. When Kroger rejected the idea, Cullen opened his own 6,000-square-foot store — tiny by today’s standards but 10 times bigger than the typical grocery store of the time. Located in a warehouse district, Cullen relied on on-street parking rather than dedicated parking, but shoppers drove in from miles around to by Cullen’s wide variety of goods at heavily discounted prices.

Retailers like A&P, Kroger, and Safeway initially resisted the supermarket format, even briefly joining efforts to outlaw them (ironic since they themselves were being attacked by efforts to outlaw chain stores). In 1936, however, John Hartford opened the first A&P supermarket. Soon the company was opening thousands of new supermarkets. Since the supermarkets served a large area, they ended up closing an average of nearly six A&P economy stores for every supermarket they opened.

The First Supercenter: Fred Meyer’s food-and-drug combo was located in downtown Portland. Knowing the value of free parking, Meyer paid his customers’ parking tickets — which also allowed him to find out where they lived. He discovered that many came from a part of northeast Portland that was still considered fairly suburban. So, in 1931, Meyer opened the biggest store in Oregon in northeast Portland’s Hollywood District. Meyer offered groceries, drugs, variety, hardware, clothing, and other goods at what he called a “one-stop shopping center.” By the time the Antiplanner moved a few blocks from this store in 1957, the store had rooftop parking.

In 1932, merchants Robert Otis and Roy Dawson opened the Big Bear store in a former automobile plant in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Thirty percent of the 50,000-square-foot store was dedicated to food, while the rest was sublet to other merchants selling hardware, auto parts, and other goods. Effectively, this was a combination of a public market and a supercenter. Otis and Dawson soon followed this up with a 150,000-square-foot store in Somerville, Massachusetts.

The supercenter format did not catch on the way supermarkets did. Few imitated Fred Meyer until the coincidentally named Frederick Meijer, son of Michigan supermarket owner Hendrik Meijer, visited a Fred Meyer store and was inspired to opened the first Meijer supercenter in 1962. Wal-Mart did not open its first supercenter until 1988, by which time Fred Meyer operated several 200,000-square-foot stores selling as many as 215,000 different products. Today, Target, K-Mart, HEB (in Texas), and Biggs (in the Cincinnati area) all have supercenters. Supercenters are also popular in Europe, where they are called hypermarts, but Holiday Plus and Auchan, two European companies that tried to open supercenters in the U.S., have both withdrawn from the market.

Fred Meyer himself died in 1979, but not before pioneering in-store banking in 1975. Within six months, Fred Meyer Savings and Loan was the second largest savings and loan company in the Northwest. Also in 1975, Fred Meyer opened his first jewelry store, which has now grown into one of the nation’s largest jewelry chains. Not even Wal-Mart sells a full array of diamond jewelry under the same roof as apples, meats, and detergents.

The First Shopping Cart: Through the early 1930s, shoppers still had to carry their groceries in a handbasket. In 1937, a Piggly Wiggly franchiser named Sylvan Goldman mounted two baskets on a wheeled rack. The now-familiar telescoping shopping cart was first developed by a Kansas City inventor in 1946.

Pretty much, these are all of the obvious characteristics of a modern supermarket. Less obvious features, including universal product codes, instant communications between cash registers and producers, and a multiplicity of distribution systems, would wait until after World War II.

From the consumer point of view, the main post-war trend was to increasing size: shortly after the war, the average grocery store in America was about 5,000 square feet in size. But they were growing rapidly. In 1955, a New Orleans store named Schwegmann’s opened a 155,000-square-foot store, then the largest in the world. Today, the average is more than 30,000 square feet.

Coming: More on American grocery trends.

Antiplanner: So, in 1931, Meyer opened the biggest store in Oregon in northeast Portland’s Hollywood District. Meyer offered groceries, drugs, variety, hardware, clothing, and other goods at what he called a “one-stop shopping center.â€Â

JK: That store would probably still be a Fred Meyer if inept planners had not killed the shopping district that it was in, Hollywood.

There was a need to get traffic moving on Sandy Blvd. which was 4 lanes in each direction with parking on both sides of the street. There were a number of stop lights as it traversed Hollywood.

In order to get traffic moving, they had to eliminate the disruption caused by left turns, into the district. They also eliminated much of the on street parking and widened the sidewalks and added street trees and drug dealer benches.

The location was on a main commute route with morning, inbound traffic still able to turn right into the district, but outbound evening traffic was able to only enter the district by very slow and inconvenient routes. A through street was blocked where it entered a “residential†section.

Having decided to eliminate the parking on Sandy, they had extra space. They used the space for street trees on wide sidewalks instead of left turn lanes, ensuring the slow choking off of customers coming from town.

Twenty years later I asked a planner about this decision to choose sidewalks and trees over accomidating customers with left turn lanes and he just said:

“But the trees are so nice.â€Â

That’s a planner: street trees are more important than a viable business district. Not even real trees, just scrawny little street trees.

Another incident that helped form my general opinion of the planning profession.

Thanks

JK

JimKarlock Says:

Antiplanner: So, in 1931, Meyer opened the biggest store in Oregon in northeast Portland’s Hollywood District. Meyer offered groceries, drugs, variety, hardware, clothing, and other goods at what he called a “one-stop shopping center.â€Â

JK: That store would probably still be a Fred Meyer if inept planners had not killed the shopping district that it was in, Hollywood.

There was a need to get traffic moving on Sandy Blvd. which was 4 lanes in each direction with parking on both sides of the street. There were a number of stop lights as it traversed Hollywood.

THWM: What strange is that this was done as a traffic flow thing, just two way streets have changed to one way streets.

JK:In order to get traffic moving, they had to eliminate the disruption caused by left turns, into the district. They also eliminated much of the on street parking and widened the sidewalks and added street trees and drug dealer benches.

THWM: Drugs need to be regulated, not criminalized.

JK:The location was on a main commute route with morning, inbound traffic still able to turn right into the district, but outbound evening traffic was able to only enter the district by very slow and inconvenient routes. A through street was blocked where it entered a “residential†section.

THWM: Though ironicly, a lot of exurban areas are planned to discourage thru traffic.

JK:Having decided to eliminate the parking on Sandy, they had extra space. They used the space for street trees on wide sidewalks instead of left turn lanes, ensuring the slow choking off of customers coming from town.

Twenty years later I asked a planner about this decision to choose sidewalks and trees over accomidating customers with left turn lanes and he just said:

“But the trees are so nice.â€Â

That’s a planner: street trees are more important than a viable business district. Not even real trees, just scrawny little street trees.

Another incident that helped form my general opinion of the planning profession.

THWM: Urban planning is a double edge sword, that’s for sure!

Anyways back to food retailing, how about IGA?

http://www.iga.com/

Also in the aspect of age there’s Fortnum & Mason in the UK.

http://www.fortnumandmason.com/

The dynamic evolving world of grocery shopping as described by the Antiplanner reminds me very much of the writings of James Burke’s “Connections” series. Our culture and economy is an ever evolving system with the fitness of each particular organization and institution very much interdependent on other system elements in existence at any one time.

The evolution of the economy can be described in the same way as biological evolution by using the “Red Queen” theory, where one has to run as fast as one can to just to stay in the same place.

The widely distributed decision making process, experimentation, and the ability to modify to suite local conditions makes the economy more robust than the top-down, centrally planned alternative.

The Antiplanner wrote: You can find at least ten different classes of grocery stores…If some government agency tried to plan the distribution of groceries…how would they do it? Would they come up with a system that offered towns as small as 1,500 people access to 30,000 different products in one store? Not likely.

I was going to let Randal go and enjoy his foray into entrepeneurial history. I was going to refrain from making any irrational associations between his thoughts on retail and his thoughts on housing. Fortunately I need not be irrational: Randal made the association explicit.

Why, for you, do grocery stores warrant an elaborate taxonomy resulting in (at least) ten different classes, but housing receives only one? Of course, I’m referring to yesterday’s post which relied on the Median Multiple, which evaluates all homes and all consumers as one market.

If some government agency tried to plan the distribution of groceries to all the households in the country, how would they do it? Would they come up with a system that offered towns as small as 1,500 people access to 30,000 different products in one store? Not likely.

OTOH, we have food deserts in many poorer areas of cities in the US.

Oh, and the interior of grocery stores is filled with HFCS and preservatives and “food” products bereft of nutrients – one must, as Pollan says, confine your shopping to the outer walls of chain grocery stores if you want to eat well and not purchase highly subsidized big ag product.

DS

Is it relatively efficient to heat and cool large grocery stores?

Energy efficiency depends upon whether your frozens are open to the air or behind glass doors (less ideal is the perforated/stripped plastic).

Then whether your doors stay open, how much roof insulation (most walls are concrete tilt-up these days, unless you are a metal building, then you need wall insulation too).

The easiest low-hanging fruit is frozens behind doors, then insulation, then leaks.

DS

apropos of nothing but my own distracted thoughts:

Anyone know of any data on how new home builders decide what price point to build for?

Anyone know of any data on how new home builders decide what price point to build for?

Putting the Current Planning hat on, in rough order IMHO (this does not include speculation where nearby large parcels still need to be subdivided) what are the important drivers for due diligence for price points:

Land cost, municipal infrastructure availability or planned installation, allowed zoning (or suspected changes in pipeline), comps, suspected delay for permit review and approval, other cost of their paper, demographic trends, exactions and fees, labor cost, proximity to open space, proximity to amenities, school proximity, arterial proximity.

DS

Thanks Dan, always a help.

Dan, as an actual home builder, I don’t agree but…

Back to the point.

I wonder why governments seem to think they can do a better job with housing development, especially affordable housing, than the market when they cannot do it with food. If they would stick with vouchers businesses would provide better and lower cost housing like they do food.

johnalt: that wasn’t a rhetorical question. I’m interested in what factors result in a decision to build a $300K home versus a $200K home. I’m mostly interested in an industry standard, some net present value model.

It seems to stand to reason that the potential profit a builder makes on a home increases with the home price. A $100,000 home can only theoretically make $100,000 profit: a $500,000 home can theoretically make a $500,000 profit.

Obviously, in reality, the profit a builder makes is less than the amount the home is sold for. So, the question becomes, is there a linear relationship between home price and profit, or not?

I seem to recall reading that profits tend to increase with homes prices, and that builders thus tend to prefer to build more expensive homes instead of “affordable” housing.

For the record, I want to reiterate that my request for an investment formula is not rhetorical. There are no implicit assumptions or premises embedded in the question. It is just a humble inquiry into the mechanisms of construction finance.

Price point fixing is an art, not a science.

At any rate,

I wonder why governments seem to think they can do a better job with housing development, especially affordable housing, than the market when they cannot do it with food.

I agree to a point: those darn single-use zones with houses on large lots were a bad unintended consequence of Euclidean zoning.

Fortunately, many planners these days (and their associations) advocate eliminating these choice-limiting development patterns and advocating more choice in housing.

But wrt food and markets, I’m not sure – absent these perverse subsidies on crops – that th’ gummint interferes in, say, grocery stores. You’d think we’d be railing against subsidizing grocery stores in food deserts if that were so, or railing against subsidizing nutritious food in grocery stores if that were so.

DS

IF New Urbanists were motivated primarily by their desire to provide choice…

What is the massive amount of extra US land that New Urbanists would need to “sacrifice to development†(to use the enviromental term) in order to provide housing for 1/3 of the US population (or 100 million new residents). Is that amount so exhorbitant that they cannot do it without leaving American Dreamers alone?

Let’s accommodate 100 million Americans at London Metro densities (4,761 people per km2). We need 21,000 km2 (out of a 9,631,420 US total) = 0.2% of US surface .

My God! If New Urbanists build their ideas on new undeveloped land, thus leaving American Dreamers alone, total urbanized US surface will go from 2.0% to 2.2% ! An environmental catastrophe!

Why is it that the only way forward for NU is to fight NIMBYs in order to displace some of the existing SFHs and at the same time supress the building of new SFHs? Can’t NUs simply be built on currently undeveloped land?

So what is that drives UGB wielding NU proponents – when their high density dreams can be accomodated on 1/500 th of the US surface without infringing on the choices of American Dreamers? – Love for NU? Or hatred for the American Dream?

C.E.

It’s sad but, UGB stem from proximity concerns.

Also some places have set up green belts.

Henry David Thoreau was correct when he said:

“Each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest, of five hundred or a thousand acres, where a stick should never be cut for fuel, a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation. All Walden Wood might have been preserved for our park forever, with Walden in its midst…”

Even NU started as a reaction to the over regulation of land use.

Though the real paradox is transport policy in North America.

Where you tend to have those on the right pushing socialism and those on the left pushing capitalism.

So what is that drives UGB wielding NU proponents… Love for NU? Or hatred for the American Dream?

*snork*

There’s a monster under your bed. Boo!

We see the ideology is scared. Why is the ideology scared to offer wider housing choice? Seems a pathetic thing to be a-skeered of.

DS

There’s no monster under your beds – just an Ettinger in your wallet and your children’s piggybank.

Single family homes don’t have to be at odds with transit.

What street trees and benches on Sandy Blvd? I don’t remember any. I just remember an unremarkable 4 lane (6 lanes in places) ugly street with strip centers and car lots cutting diagonally across the nice residential street grid.

Fred Meyer turned it’s back on Sandy and created an access instead from Broadway … it was always packed morning noon and night.

Nice store, btw

Buy local?