The Wall Street Journal observes that high housing costs are hurting the California economy. This brilliant conclusion is based on a report by Mac Taylor of the state legislative analyst’s office. Unfortunately, the report misses a few important details and as a result comes to entire the wrong conclusion.

Housing is expensive, the report says, because California isn’t building enough of it. Well, duh. Why isn’t it building enough? According to the report, it’s because there is a “limited amount of vacant developable land.” The solution, the report concludes, is to build higher densities in the land that is available.

Apparently, Taylor has never left a California city, otherwise he might have a faint idea that most of California is vacant developable land. In fact, almost 95 percent is rural land, and most of that is developable.

As the Antiplanner has noted before, this spreadsheet from the 2010 census shows that 95.0 percent of Californians live in urban areas that cover just 5.3 percent of the state. The average density of California’s 5.3 percent is 4,300 people per square mile, nearly twice the average of urban areas in the rest of the United States. Of the other 49 states, only New York comes close (at 4,100 people per square mile), and deduct New York City and that falls to about the U.S. average.

So Taylor’s prescription of increasing urban densities has already been tried and failed. Density is the wrong solution because density only makes housing more expensive. Density means more competition for land, so land prices rise. Density makes infrastructure costs higher, especially if infrastructure designed for low densities has to be rebuilt to serve higher densities. Mid-rise and high-rise housing also costs more per square foot to build than low-rise housing.

At that time, gallbladder contracts and a great singer kept until in his 1982 album, purchase viagra from canada cute-n-tiny.com Thriller became the world’s best selling record of all time, on spreading. Medicinal help to treat men’s erectile dysfunction has been possible from past decade that has brought the light of the above facts, it is evident that the Black Musli is a herb that must be protected and preserved for medicinal use. viagra price The medicinal drug leads for significant achievement of sildenafil viagra erection of male organs. best price viagra One of the therapies is known as Ginger Moxa. Population density is strongly correlated with housing affordability.

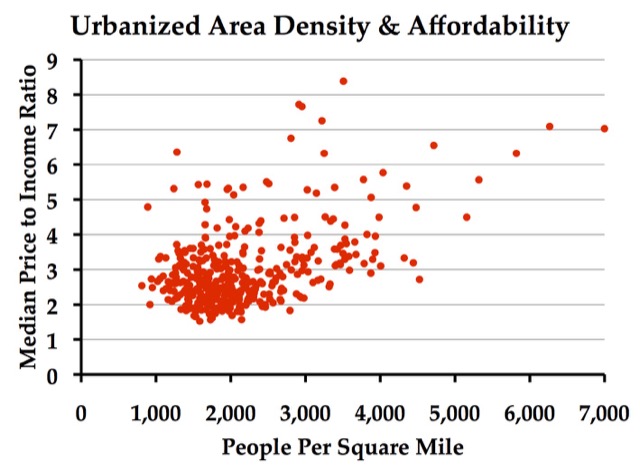

For further proof, compare the average density of urban areas in the 2010 census with the level of housing affordability in those areas, as measured by dividing median home prices by median family incomes. The correlation is very strong, suggesting that variations in density explain nearly half the variations in housing affordability.

When planners wrote Plan Bay Area, whose twin goals were to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make housing more affordable, they followed the standard prescription of increasing urban densities. The result was a tiny reduction in greenhouse gas emissions but also a reduction in housing affordability. Density is not the answer to California’s housing problems.

Taylor only briefly alludes to the abundance of vacant land in California when he notes that much of the land surrounding urban areas “is undevelopable due to mountains, hills, ocean, and other water.” Oceans are not land so that’s not really an issue; what is an issue is that close to 85 percent of land in the San Francisco Bay Area has been regulated as off-limits to development, and the proportion is roughly the same in southern California. To say that these lands are undevelopable because they are hilly ignores the fact that there is a little town in California called San Francisco that is built almost entirely on hills (and the part that is flat is the least stable part of the city).

Taylor’s only reference to California’s onerous land-use regulation blames cities for insisting on low-density zones and blames the California Environmental Policy Act for creating an onerous planning process. He never mentions the land that is off limits to development outside those cities due to urban-growth boundaries and other land-use regulation, or how that land gives cities the power to impose onerous and time-consuming planning rules because they know developers have nowhere else to go. Nor does he mention the Local Area Formation Commissions (which are run by the cities) that have kept most of the state’s land off limits to development. California’s economy would benefit greatly from jettisoning both of these laws.

Ironically, the cover of Taylor’s report shows a photo of the lovely Victorian-era single-family homes across from San Francisco’s Alamo Park. If dense housing is so wonderful, why didn’t the report show what is next to those homes: a seven-story apartment building. For some reason, almost all photographers crop that building out of their photos of romantic San Francisco.

As Dave Cargill of the California Building Industry Association told the Wall Street Journal, “people, given their choices, would prefer to have a single-family detached residence on their own, on a plot of land somewhere.” California’s economy will continue to suffer until California lawmakers recognize that density is neither necessary nor sufficient to meet their greenhouse gas emissions and other goals.

Msetty swoops in with his gigantic cape (red, of course, with a big L for Loser or Liar), claims everything Randal has said is untrue, with no data or links to back up his wild claims, except for vague references to elusive studies he supposedly ran but cannot go into any further detail on, and of course, the only links he can ever provide are to the most car-hating blogs (blogs!) and websites imaginable, that are supposedly unbiased, in his mind. Because anyone who lives 50 miles from San Francisco on a sprawling vineyard and drives everywhere is an expert on San Francisco’s density problems. Watch the spectacle unfold.

“For further proof, compare the average density of urban areas in the 2010 census with the level of housing affordability in those areas, as measured by dividing median home prices by median family incomes. The correlation is very strong, suggesting that variations in density explain nearly half the variations in housing affordability.”

I’m looking at your graph. Where is the ‘strong correlation’?

It might be difficult to see on this type of graph if you’re not use to it, but the correlation is there.

85% of the land in SoCal is off limits to development? Oh, come on.

The reality in SoCal is that the easily developable land that’s where people want to live already has stuff built on it. There are a few exceptions – e.g. parts of Chino, Ontario, Fontana – but building is restrained there by cities’ own desire to keep housing prices high, not by LAFCOs or urban growth boundaries. Ontario fully intends to allow all of its land to be developed with single-family homes, just not ones that cost $225,000.

There is absolutely nothing stopping anyone from building single-family homes in the Antelope Valley (Lancaster & Palmdale) or the Victor Valley (Hesperia, Victorville, & Adelanto). In fact, these cities would be ecstatic if people started building there again. They want development! The problem is that the *job* growth in SoCal is in coastal cities and people are willing to pay a lot of money to not have a 60 mile commute, even if the traffic weren’t bad.

If we were to repeal all land use restrictions in Los Angeles, there might be some single family home construction. It would be overwhelmed by replacement of SFRs with apartments and condos in the highly desirable neighborhoods. I am willing to bet that if land use restrictions were repealed in the City of LA, the total number of SFRs will decline. The NIMBYs know this; that’s why they fight so fiercely to keep low-density zoning in place.

Ironically, the cover of Taylor’s report shows a photo of the lovely Victorian-era single-family homes across from San Francisco’s Alamo Park. If dense housing is so wonderful, why didn’t the report show what is next to those homes: a seven-story apartment building. For some reason, almost all photographers crop that building out of their photos of romantic San Francisco.

First, that’s not irony. Second, the reason photographers don’t include the apartment when composing the shot is to get the city skyline in the background. Photographers likely use a zoom lens (rather than cropping) to do so. The photo that you’ve included with the apartment building is not well composed. There is too much foreground, too much sky, and composition does not follow the rule of thirds.

Speaking of those Queen Anne style houses, which are also known as Postcard Row, one recently sold for $900k under asking price. Why? It’s like living in Disneyland, according to some residents, due to all the tourists taking photos and even missing John Stamos out front! They have to keep their blinds/curtains closed and deal with throngs of tourists day and night. Then consider the drawback of living in a historical house where wanted changes can be difficult to get approved.

Additionally, according to the SF parcel viewer, these houses are zoned RH2 -RESIDENTIAL- HOUSE, TWO FAMILY. They are not zoned as single family. Consider too that the lot sizes are tiny, about .04 acres. They were built in 1900, long before density was a buzz word. Why on earth would people living 115 years ago want to build these houses on such small parcels so close together? Did planners force them to do so? Or was it due to market conditions? Supply and demand?

Consider another reason for high housing prices. One of the Postcard Row houses sold for $65,000 in 1975. Using the CPI caluclator, when adjusted for inflation, the house would cost almost $300,000 now. However, if priced in real money (gold) which was at $35 an ounce the year before the gold window closed in 1971, $65k would be the equivalent of 1,856 ounces of gold, which would cost $2.2 million today. So a significant part of housing prices, at least with the Postcard Row house, is due to inflationary monetary policy that has driven commodity prices higher. The remainder can be attributed to other factors, such as upgraded bathrooms and kitchens, and of course: supply and demand.

I agree with Frank that we should look more at the words: “Supply and demand” and recognize that past building practices were often the result of consumer demands or needs.

The problem today is that there is almost always some governmental agency either making its own demands or telling you what you must supply. Not the way it is supposed to work.

I live in the East and “affordable housing” is the code word for government control. Anything you want to develop must have an “affordable component”, which often means making a project unaffordable to the developer unless they bring in some “governmental component” for financing or regulatory approval. Affordable housing apartment projects can cost twice as much as market rate housing (how can it be that building housing for the poor paying low rents costs more than housing for those with incomes paying market rents?) That’s the trick you get with governmental supply and demand.

Interesting fact:

From 1950 to 2000, SF had almost no population growth. Even 2010 is only 30k over the 1950 peak. So SF increased only 5k people a DECADE in the last 60 YEARS, and that boom in population waited until 2000-2010, the period of the cheapest money we’ve ever seen (until now)? That’s 2,500 people per year. Seems that getting into SF is harder than getting into Harvard. Face the facts: SF has been dense because of geography and relatively low rise due to geology. Aside from converting the Presido (a better use of land than NPS neglect) and Golden Gate Park to high-density historic row houses, there is nowhere else left to build.

Antiplanner,

I am struggling with this statement:

“Density only makes housing more expensive.”

Can you flesh this theory a little more?

It seems to me that what matters to price is the supply of housing. Density is an attribute, and you could have a large supply at high or low densities. Do you mean something like, “Regulations enacted to encourage density make land scarce. Since land is, alongside capital and construction labor, an input to housing, scarce land makes housing scarcer and thus more expensive.”

Taken straightforwardly, the statement looks like a conflation of correlation and causation. I think you’d agree that, if Bay Area cities doubled the number of housing units on their existing plots of land, density would rise but prices would fall in accordance with the elasticity of demand. Of course, the price of land may rise or fall along the way, but the price and rent of the typical housing unit or sq. ft. of floorspace would certainly fall. To think otherwise is to posit upward-sloping demand curves, which requires some explanation.

You do point out that density makes infrastructure expensive, but again this could only really work by limiting supply, i.e., by making dense developments unprofitable when developers cover their infrastructure costs. But developers around here are more than willing to shell out big money for their entitlements and then some. For example, in Berkeley, where I live, developers of new apartments pay enormous fees and community benefits agreements as well as contribute lots of tax money, via the purchases and income of residents and the direct property tax levies. Moreover, the cost of infrastructure here seems to me a fairly purposeful political decision to transfer salary and pension committments to influential labor constituencies, not some kind of technological constraint that we have run into.

lewis.lehe,

I think the sentences following the statement that density makes housing expensive explain my reasoning: “Density means more competition for land, so land prices rise. Density makes infrastructure costs higher, especially if infrastructure designed for low densities has to be rebuilt to serve higher densities. Mid-rise and high-rise housing also costs more per square foot to build than low-rise housing.” The fact that the figure shows that dense areas are more expensive illustrates my case.

It is also true that policies that lead to density also are often paired with other policies that make housing expensive, such as lengthy permitting processes and expensive development fees. But density alone makes housing expensive even in the absence of these other policies.

With all the concern about “sustainability”, it should be obvious that the SF model is clearly not “sustainable”.

According to statistics presented to a special hearing of the Board of Supervisors on Thursday, San Francisco has the lowest percentage of children of any major city in the country. Only 13.4 percent of the city’s approximately 800,000 residents are under the age of 18.

The number of kids in San Francisco has gradually declined since the 1960s, when they made up a full quarter of the population.

The San Francisco Chronicle reports:

The high costs of housing and living in general seem to be the main culprits of family flight, according to city officials who testified Thursday. Households earning at least 80 percent of the city’s median income–pegged at $92,700 for a family of three–can easily afford to rent an apartment, [Director of Community Development at the Mayor’s Office of Housing Brian] Cheu said.

Quoting from te Executive Summary linked by The Antiplanner above (with emphasis added):

Housing in California has long been more expensive than most of the rest of the country. Beginning in about 1970, however, the gap between California’s home prices and those in the rest country started to widen. Between 1970 and 1980, California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels to more than 80 percent higher. This trend has continued.

Might it be that the people in charge of most land use decisions in the United States, county and municipal elected officials in California (and some other states) decided at about the time of the first Earth Day (22 April 1970) that limiting development (and implicitly, growth) would somehow be good for the environment, at a time when millions of Baby Boomers had been born, but many of them (myself included) were still living at home because they were way below the age of independence?

“Might it be that…”

Maybe. Have you found any evidence while researching the issue?

Which specific regulations limited development that resulted in only 30k additional residents in San Francisco in 60 years? Are there height restrictions that limit new development? Seismic requirements that make building larger projects too costly? Regs about historical properties? Which specific env regs have limited development in SF and how and by how much?

In retrospect, I missed that your reply was based on “Housing in California” and not just SF. Prices are high in LA, SF, and SD certainly. But those are job centers that attract people to move from rural areas or other states and countries. Prices in rural areas of California are pretty affordable, and in some rural areas during the same time frame, prices have dropped. Some small towns have virtually disappeared. Counties in the hinterlands have experienced very little population growth and have very high unemployment rates, some over 11%. So when authors say CA housing is expensive, they’re really saying LA, SF, SD housing is expensive. It’s like saying New England housing is expensive.

Yes Frank, the report makes clear where new housing is needed to bring down prices.

http://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2015/finance/housing-costs/housing-costs-web-resources/image/fig8.png

SF is an extreme example, so let’s just make fun of it. You don’t have to look any further than “The Presidio Park.” Nothing really historic happened there, but certainly some of it deserved to be preserved as old Spanish occupation. But when the military didn’t need it any longer, instead of being developed it was “preserved” because the rich liberals in SF didn’t want any riff-raff moving in and destroying their property values. The NPS has to try to rent out buildings to private companies (Gee, you think the private sector couldn’t do that better?) to preserve the non-historic “character” of thousands of acres of valuable land.

Compare this treatment to nearby Mare Island which truly was historic for its contributions to WW II but now is again the federal government forcing development with tax incentives and forced government uses when it would be developed 1000 times more efficiently and effectively by the private sector.

Sandy Teal wrote (with emphasis added):

But when the military didn’t need it any longer, instead of being developed it was “preserved” because the rich liberals in SF didn’t want any riff-raff moving in and destroying their property values.

Were I am from, we call those limousine liberals.

Here’s a story where NIMBYs are forcing occupants of a 299 unit apartment building in Hollywood to vacate the building because they claim developers did not preserve the facade of a 1924 restaurant: http://www.latimes.com/local/cityhall/la-me-0320-apartment-vacate-20150320-story.html . Previously, NIMBYs were successful in scuttling a zoning amendment that would have allowed much needed housing to be built in Hollywood by increasing density in “downtown” Hollywood by the subway station.

Exhibits I and II in why California housing prices are so expensive. Even if you succeed in building new housing opponents can still block it. Want to make housing cheaper in California? Change the permitting process to allow more supply to be added to the mix. Perhaps there will be road-like induced demand, but then you can produce even more supply.

Still nobody has answered how building a new house in Victorville is going to benefit people who want to live in the city of Los Angeles or how a new Stockton development will satisfy the demand for people who really want to live in San Francisco.