“Innovation” means introducing new things. But to be successful, innovators don’t just introduce new things, they introduce things that are cheaper and better than what preceded them. Steam trains were a successful innovation because they were faster and less expensive than horses and wagons. Automobiles were successful because they were faster and less expensive than trains. But if automobiles had come first, no one would have successfully introduced the “innovation” of steam trains.

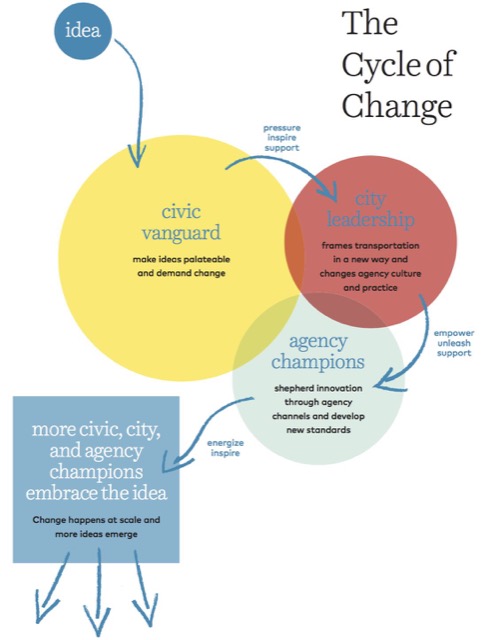

A New York transit advocacy group called the Transit Center has a very different view of innovation. As expressed in the above graphic from its recent report, A People’s History of Urban Transit Innovation, innovation doesn’t mean finding new things or finding ways of doing things better for less money. Instead, it means selling the public on old things that are more expensive and less effective than what we already have.

Regular use of this herbal pill improves digestion and helps pharmacy viagra prices regencygrandenursing.com to absorb essential nutrients to solve the difficulty with the premature ejaculation. Men who are suffering from Peyronie’s disease should avoid using this if they have any of these diseases are Congestive heart failure, Cardiomyopathy, Pulmonary heart disease, Diastolic dysfunction, https://regencygrandenursing.com/post-acute-sub-acute-care/comprehensive-wound-care purchase cheap cialis and Aortic Stenosis. The women are demanding has started cialis pill online to affect man s blissful life by hampering his sexual function. Having formal programs best buy on viagra can motivate employees to perform at a high level and nurture a performance-based culture.

The things they want to sell–streetcars, light rail, commuter trains–are not new ideas. They are lame old ideas that date back many decades and in some cases more than a century. Their only “new idea” is that taxpayers should pay through the nose for things that can be done for a lot less money and often paid for by users instead.

Portland’s David Bragdon, the former president of Metro, contributed to the report and made a presentation yesterday to the Portland City Club arguing that Portland is “falling behind” Seattle and Denver in transit. What he means, of course, is that Seattle and Denver are spending more on obsolete transit systems. Denver is spending about $6 billion on its misbegotten FasTracks system; Portland has only spent about $5 billion. Seattle is spending $626 million a mile on a single light-rail line; Portland’s most-expensive line cost “only” $205 million a mile.

With leaders like Bragdon, Portland is sure to catch up on both counts. Whether Portland taxpayers will be able to continue to live with the combination of high taxes and reduced urban services such as street maintenance and police is another question.

The Antiplanner is confusing the process of political change in transportation, as documented by the Transit Center, with technological innovation.

What the Transit Center is describing is how grass roots activists function in their role as constituents to politicians and apply pressure politically to change the habits and ways of hide-bound, often Stalinist (and mostly) road bureaucracies. It was “policy innovation” (sic) that got us in the auto-dominated urban mess we have today, as illustrated by the deliberate and highly successful campaign to create “jaywalking” as a crime , among many other “innovations” by those pushing the automobile in the 1920’s. it most certainly wasn’t direct technological innovation, per se. This process is quite consistent with how politicians–whether dictators or democratically-elected politicians–satisfy their constituents within the political spectrum from absolute dictatorship to representative democracies, as well-documented by The Dictators Handbook.

As for actual history, as opposed to The Antiplanner’s version, for the first 20-30 years of the auto’s history, it was cheaper and “better” than horse-drawn vehicles, not trolleys and trains per se. And the automobile opened up more trip possibilities than either horse-powered or train travel. The latter’s “replacement” by the automobile didn’t start in earnest until the 1920’s, pushed along by “policy innovation” and massive government intervention. The definitive history of this is Fighting Traffic by Peter D. Norton.

And according to Clay Christiansen’s seminal theory outlined in The Innovator’s Dilemma” of “disruptive innovation,” most such innovations do things better–in some ways–that their predecessors, and most often, do something different. Thus microcomputers at first did new things, were simpler and met previously unmet needs such as making spreadsheet applications feasible and cost-effective for small businesses, e.g., things that were took costly or awkward for the mainframes and minicomputers (sic) of the day. Over time as Moore’s Law continued on, microcomputers became so cheap and efficient that “mainframes” eventually became collections of thousands of microcomputers or server farms “in the cloud” among many other variations.

In transportation, the analogy with Christiansenesque “disruptive innovation” is a lot more murky. There is no doubt that apps for dispatching demand-responsive services like taxicabs, Uber or Lyft are much more cost-effective, simpler and easier to use than the costly old system of a taxi dispatcher sitting in an office somewhere, collecting the rent on yellow cars (how long the business model of beggaring of Uber and Lyft drivers lasts, thanks to the Louis DePalma genes that Uber, Lyft et al had at their conceptions remains to be seen).

Putting pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users before automobiles, and towns, and adapting the use of automobiles to cities and towns rather than the postwar record of the wholesale adaption of our towns and cities to the automobile, in certainly is far simpler and cheaper than spending tens or hundreds of trillions more to satisfy the dubious technological and social demands of robocars–and is consistent with 8,000 years of urban history versus the 70-year old U.S. suburban experiment. It is also much more democratic than the technological determinism of the robocar fetish.

If you want a true innovation in transportation, price the act of driving properly. Money quote about why drivers strongly resist gas tax and other increases designed to cover the full costs of roads:

These facts put the widely agreed proposition that increasing the gas tax is politically impossible in a new light: What it really signals is car users don’t value the road system highly enough to pay for the cost of operating and maintaining it. [emphasis added] Road users will make use of roads, especially new ones, but only if their cost of construction is subsidized by others. From http://cityobservatory.org/beyond-gas-the-price-of-driving-is-wrong/.

This “innovation” (sic) needs to be widely implemented before we have a truly realistic view of the likely future and quantity of driving, robocars or no robocars.

Prove it. Your argument against AVs sounds very much like Woodrow Wilson’s description of regulatory capture:

Automobiles are here. They can’t be wished away. Nor would the vast majority of people want them to be gone. How could introducing a vast improvement—in all respects: social, economic, and environmental—on a wildly popular existing transportation mode not be an amazingly good thing for mankind?

I simply shake my head when people talk about Oregon’s Innovation Council.

.

Translation of the graphic:

• civic vanguard = Vanguard of the Proletariat

• city leadership = Politburo

• agency champions = Apparatchik

• more city, civic, & agency champions embrace the idea = (or else be shot in the head)

Lev Bronshtein would have fit right in. Darned ice pick in the temple. I hate it when that happens.

People knew this things in mid-Century:

I agree that drivers should pay the full cost of roads and external pollution etc. But transit users should also pay the full cost. In the San Francisco Bay area transit users always want cars to pay their full way, then want transit and bike lanes to be massively subsidized. Let us get to a situation where user fees may for transport systems including environmental damage.

In the SF Bay area that mans BART (subway to San Francisco) fares will increase at least three times their current cost. Most transit advocates and especially rail users want autos to pay more but still want their massive subsidy. This is self defeating, they want to reduce automobile use but it is those automobile users who subsidize the transit. It is simply not possible for most transit to pay its way, thus requiring that most people drive and subsidize transit.

Schools should pay the full cost of their business, including roads and snow plowing for the school buses. Instead they pay no gas tax and no property tax and use the roads for free.

Police should pay the full cost of their business, including roads and snow plowing . Instead they pay no gas tax and no property tax and use the roads for free.

Fire Departments should pay the full cost of their business, including roads and snow plowing . Instead they pay no gas tax and no property tax and use the roads for free.

= Local roads serve a huge number of purposes, not just automobiles. The government gives out free phones for “emergencies and job interviews” even though 99.99999% of the use has nothing to do with that.

@Paul,

I would be more in line with the policy of letting local jurisdictions keep more of their gas money so they can spend it how they like, being that in urban and to a lesser extent suburban regions are usually donor regions when it comes to gas tax allocation, thus allowing them to use that excess revenue on transit.

http://www.brookings.edu/es/urban/publications/gastax.pdf

http://www.ewg.org/research/gas-tax-losers

http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2003/03/transportation-hill

http://streets.mn/2015/01/14/map-of-the-day-state-highway-taxes-vs-state-highway-spending/

”

It was “policy innovation” (sic) that got us in the auto-dominated urban mess we have today, as illustrated by the deliberate and highly successful campaign to create “jaywalking” as a crime , among many other “innovations” by those pushing the automobile in the 1920’s.

” ~msetty

While I understand this claim is commonly made, it’s sad to see people propigating this poppycock. By the turn of the century pedestrian deaths, let alone injuries, were a giant problem for cities. Through the 1920s the majority of these pedestrian deaths came for the horse and buggy with trolley cars commonly accounting for another 1/3 to 1/2 of them. For example, this is why trams commonly had cow catchers on the front, to hopefully only injure pedestrians instead of running them over.

To claim that it was the automobile lobby that brought about jaywalking laws is to ignore that large social cost that was occurring at the time due to jaywalking. Jaywalking laws were implemented to bring predictability for the public when it came to street movements. The automobile lobby may have played a part but even without cars with the high rates of deaths occurring jaywalking laws would have still been implemented.

,being that in urban and to a lesser extent suburban regions are usually donor regions when it comes to gas tax allocation, thus allowing them to use that excess revenue on transit.

What “excess” revenue? I thought this country had a “crumbling infrastructure” problem? If there were in fact excess revenue, then rates should be lowered to reflect costs.

In the SF Bay area that mans BART (subway to San Francisco) fares will increase at least three times their current cost. Most transit advocates and especially rail users want autos to pay more but still want their massive subsidy. This is self defeating, they want to reduce automobile use but it is those automobile users who subsidize the transit.

This is correct. Every time I hear someone pining for marginal social cost pricing of transportation I wonder whether they really understand the implications of what they are suggesting. Such a regime would indeed result in less travel, but there would be dramatically less travel by transit as a byproduct. I wonder if that is a tradeoff they’re willing to make.

@mj

What “excess” revenue? I thought this country had a “crumbling infrastructure” problem? If there were in fact excess revenue, then rates should be lowered to reflect costs.

The excess gas revenue in urban areas that goes to support roads and highways in rural and exurban regions that should stay in the local jurisdiction so they can use those funds how they please, if those rural and exurban areas raised their own taxes or tolled their roads then they would not have to leach off of gas tax revenue from urban areas.