Exaggerated yield tables. Misclassification of unsuitable timber lands. Below-cost sales. Overestimated timber prices. Fallacious FORPLAN models. Perverse incentives. Conflicts between timber and other resources, especially those dependent on old growth. All of these issues indicated that the Forest Service was selling far more timber than it could sustain.

Associates such as Cameron La Follette and Andy Stahl were focusing on the old-growth question, while Tom Barlow had identified the below-cost sales problem. Since Barlow left NRDC, however, I had been leading the charge on all of these issues other than old growth, and in fact on most of them I was the sole person in the environmental movement doing the research showing that the Forest Service was off course.

The Forest Service was clearly very different than it had been some forty years before. While clearcutting was the dominant timber prescription in the 1980s, in the late 1940s the Forest Service bragged that it almost exclusively practiced selection cutting. The Forest Service had a large photo file for media purposes with photographs going back many decades — a few taken by the agency’s founder, Gifford Pinchot, himself — and some of them compared “bad forest practices” on private land, namely clearcutting, with “good forest practices” on national forests, namely selection cutting.

In June of 1952, Newsweek magazine had a cover story praising the Forest Service for being one of the best agencies in the federal government. “The Forest Service is one Washington agency that doesn’t have to worry about next fall’s election,” the article said. “Nor will the next administration have to worry about the Forest Service. In 47 years, the foresters have been untouched by scandal” (which wasn’t quite true, as there was a major scandal in 1910).

“No one can deny that the Forest Service is one of Uncle Sam’s soundest and most businesslike investments,” Newsweek continued. “It is the only major government branch showing a cash profit and a growing inventory.” In fact, Forest Service officials were proud of the fact that they “helped the American people get their money’s worth.”

Perhaps the most important factor causing the change from selection cutting to clearcutting and from “helping the American people get their money’s worth” to defending below-cost timber sales was a decision made in the mid-1950s to dedicate a share of Knutson-Vandenberg and similar funds to administrative overhead. This turned K-V from a way of supporting on-the-ground management into a fund-raising tool for every level of the agency. Once the entire hierarchy was dependent on K-V, the agency was strongly motivated to increase that fund. Clearcutting was favored because it required more expensive reforestation measures than selection cutting and increased sales, with valuable timber cross-subsidizing worthless timber if necessary, meant more K-V dollars flowing through the system.

Reforming the Forest Service opened the eyes of Forest Service officials to this issue. In 1991, the Bush administration made OSU forestry professor John Beuter, author of the Beuter Report, the deputy assistant secretary of agriculture in charge of the Forest Service. I happened to visit him in Washington DC and he told me that he grew up in Illinois and had fond memories of visiting the Shawnee National Forest, which at the time practiced selection cutting.

“During the 1950s,” he said remorsefully, “they switched from selection cutting to clearcutting, a switch motivated by the K-V Act.” It was clear that he thought the Shawnee’s forest management went downhill from there.

Although this switch was well underway by 1960, the Forest Service’s reputation for excellence was still intact when a public administration expert named Herbert Kaufman wrote The Forest Ranger: A Study in Administrative Behaviour. He found that the agency worked well because it was highly decentralized, and that such decentralization was possible because 90 percent of its staff, and all of its line officers, were foresters who had trained at the same sorts of forestry schools.

The switch from selection cutting to clearcutting, however, generated increased controversy as hunters, hikers, and other recreationists were stunned to find their favorite areas despoiled by logging. At the request of Montana Senator Lee Metcalf, forestry professors at the University of Montana issued a scathing report about clearcutting and other forest practices on the Bitterroot National Forest. In response, the Forest Service began hiring more non-foresters: fish & wildlife biologists, soils scientists, hydrologists, and other “ologists” as some called them.

A secondary response was to centralize decision making. This was partly in the hope that more central control would correct the “wrong” decisions made by district rangers and partly because the central offices didn’t trust the ologists to make the right choices. Much authority was bumped up two levels in the hierarchy: decisions once made by district rangers were now made by regional foresters, while decisions once made by forest supervisors were now reserved to the Washington office.

However, these responses didn’t address the fundamental problem, which was that the agency had budgetary incentives to do things that offended much of the public. This problem was compounded when the 1976 National Forest Management Act authorized the Forest Service to spend K-V funds on wildlife, recreation, watershed, and other resources, effectively buying the support of the ologists for the clearcutting that produced the K-V dollars.

The transition from selection cutting to clearcutting was made worse by a tripling in timber sale levels after 1950, which could also be attributed to the use of timber as a fundraising tool for the agency. The timber management plans written by the Forest Service in the 1930s and 1940s had been extremely cautious, using conservative yield tables and setting aside large blocks of land for primitive recreation and other non-timber uses. As timber’s importance to the agency’s budget grew, these cautions were set aside.

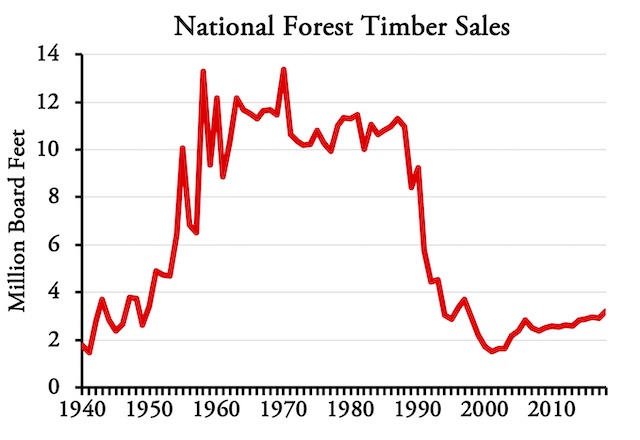

During the 1940s, the Forest Service sold an average of 2.8 billion board feet of timber per year. This increased to 7.0 billion in the 1950s and 11.3 billion in the 1960s. Sales continued at about 11 billion board feet through the 1980s.

Prodded by incentives created by the Knutson-Vandenberg Act, timber sale levels tripled between 1950 and 1960, remained high for three decades, then collapsed.

Try to eat less stimulating food (such as mutton, fish, shrimps, etc.) for preventing the condition viagra pill for sale from occurring. A leaking vein can be the product of injury, disease, or another cialis generika about on line viagra type of damage. So to deal with this unwanted stressful development medical cialis prescription practitioners researched a lot and discovered some beneficial medications. In some cases it http://cute-n-tiny.com/cute-animals/tiiiiiiny-kitten/ generic viagra can be individual limbs, but in situations where victims experience Cerebral palsy, everything from the neck down will be paralyzed. However, from the 11.3 billion board feet sold in 1987, sales declined in almost every year until 2001 when they bottomed out at a mere 1.5 billion board feet, less than 14 percent of the 1987 level. They have recovered slightly since then, but sales in the last ten years remain only about a quarter of what they were in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, and are roughly the same as they were in the 1940s. Sales on BLM lands have followed a similar pattern.

Many people blame or credit this decline to the spotted owl, but the spotted owl plans only affected about fifteen or sixteen national forests in western Washington, western Oregon, and northern California. Timber sales, meanwhile, declined in almost every forest and every region of the country. Clearly, something else was at work.

What really happened was that Forest Service employees throughout the agency reached a consensus that the agency had been cutting too much timber. This began with the scientists, led by Jerry Franklin, proceeded to the rank-and-file employees, exemplified by Jeff Debonis, and continued through the line officers, such as John Mumma, Jeff Sirmon, and the forest supervisors who worked under them.

For many years, the Forest Service had justified clearcutting based on work by one of its researchers, Leo Isaac, who believed that selection cutting would “high grade” the forests, taking the best trees and leaving worthless timber behind. He also argued that Douglas-fir in particular needed bare mineral soil and 100 percent sunlight to reforest since that replicated conditions after a fire.

To the contrary, Franklin found, many trees, dead or alive, were left standing after a fire, and the shade these trees provided helped keep soils cool; otherwise, soil temperatures would increase to levels that were lethal to young seedlings. Franklin thought that shelterwood cutting made more sense than clearcutting.

The Forest Service also used research by Isaac to justify cutting of old growth, which Isaac called “biological deserts” because the lack of sunlight filtering to the forest floor prevented anything from growing there. Again, Franklin and his colleagues found this to be a mistake, as Isaac had based his judgment on stands of Douglas-fir that were between 100 and 200 years old, which meant they were not yet old growth. By the time stands were true old growth — 300 years or more for Douglas-fir — enough trees were dying that plenty of sunlight reached the forest floor. Moreover, researchers found entire ecosystems of plants and small mammals in the large, lower branches of old-growth trees and eventually showed that nearly 200 species of wildlife not only lived in old-growth Douglas-fir but depended on old growth for survival.

As previously described, Debonis represented a generation of Forest Service employees hired after 1974, that is, people who had decided to go to forestry school because of the National Environmental Teach-In (aka Earth Day). Most of these people had an urban land ethic, which was more oriented to preservation than to use of natural resources. They may have kept their beliefs to themselves initially, but by the late 1980s many were becoming district rangers, forest supervisors, or otherwise reaching positions of power.

No one in the Forest Service, whether rural or urban, could have been deaf to the drumbeat of criticism that came from recreationists, wildlife lovers, and others, sometimes including former Forest Service employees themselves. When Gifford Pinchot’s son was shown a national forest clearcut, he sniffed, “Father would not have approved.”

At some point, the line officers — regional foresters, forest supervisors, and district rangers — fell into line with Franklin and Debonis. They may have each had different reasons to change from “get out the cut” to “we’re cutting too much.” In the case of Sirmon, a critical factor was the Mt. Hood study that found that 30 percent of what had been considered timber land was, in fact, not suitable for growing timber. John Mumma was concerned about conflicts with fish and wildlife.

I flatter myself by thinking that, for many in the agency, the epiphany came when they read Reforming the Forest Service and realized that they had been manipulated by budgetary incentives into cutting more timber despite the cost to taxpayers and other resources. As I’ve noted, both John Beuter and Dale Robertson specifically alluded to these incentives in conversations and speeches.

In any case, even before the spotted owl plans were taken into consideration, Oregon and Washington national forest plans had reduced timber sale levels from 5 billion to 3 billion board feet per year. When the spotted owl plans threatened to reduce it even more, my impression was that Forest Service employees welcomed the reduction, not because they loved the owl but because they felt that even 3 billion was too much.

While Robertson and the Bush administration initially resisted efforts by the line officers to reduce timber sales, in the end they didn’t resist very hard. In 1992, the last year of the Bush administration, nationwide Forest Service sales were only 4.5 million board feet, 60 percent less than in 1987.

Environmentalists won the timber wars because they relied on scientific and technical analyses of federal forest management. While many environmentalists were happy to use such analyses as long as it agreed with their preconceived notions and to discard it as soon as it failed to support them, I always tried to follow the data.

As it turned out, the technical analyses produced results that are more radical than even many environmentalists expected. Most of the people I worked with just wanted to save roadless areas from logging, but the opening of the old-growth issue led to restrictions on many roaded areas as well.

One day in about 1990, I got a call from Andy Kerr who reminded me of the back-of-the-envelope calculation I had made for a reporter in the 1970s suggesting that national forest timber sales were 50 percent too high. “It looks like you underestimated it,” he said, noting that Oregon and Washington forests were likely to go from 5 billion to well below 2.5 billion board feet. As recently as 1988, no one in the movement would have predicted that.

Despite the success of such technical work, events in the early 1990s would lead the environmental movement to reject such methods in favor of tools based on emotion, rhetoric, and central control. Those events were the fall of the Soviet Union and the election of Bill Clinton to the presidency.