Housing prices continue to rise and in many places they now exceed prices at the peak of the 2006 housing bubble. Incomes in many regions have failed to rise to match those prices, with the result that housing is unaffordable—that is, median home prices are at least four times median family incomes—in California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, as well as the Boston, Miami, and New York urban areas.

Click image to download a PDF of this five-page policy brief.

Click image to download a PDF of this five-page policy brief.

Prices are high in these areas because of urban-growth boundaries or other restrictions on development of rural areas at the urban fringes of these states and regions. Collectively known as growth management, such restrictions increase the price of developable land, allow cities to impose development restrictions without fear that developers will go outside the cities, and increase labor costs as home construction workers fight to find affordable housing along with everyone else.

Instead of abolishing these restrictions, the people who imposed and support them want to rezone neighborhoods of single-family homes for higher densities. Oregon and Minneapolis have both abolished single-family zoning. California has proposed to do so in transit corridors. Yet there is no evidence that single-family zoning makes housing expensive or that building multifamily housing will make housing more affordable. Rather than debate the evidence, advocates of density have resorted to calling supporters of single-family zoning names such as NIMBYs (not in my backyard) and racists. This paper will show that most Americans live in neighborhoods of single-family homes because they want to and that their preferences are both legitimate and not a threat to housing affordability.

The Mania for Density

A century ago, most urban planners wanted to help people move out of dense, inner-city tenements and into lower-density single-family neighborhoods that they thought were safer and healthier. In the 1920s, that goal was being achieved thanks not to urban planners but to affordable, mass-produced automobiles such as the Model T Ford, which gave working-class families affordable mobility to reach affordable housing in the suburbs.

Yet the exodus of working-class people from the cities led some planning advocates to question the goal, starting in class-conscious Britain. Socialist C.E.M. Joad was upset that people whose tastes in clothing and music were different from his own could be seen “cackling insanely in the woods” and “upon seashores and river banks, lying in every attitude of undress and inelegant squalor.” Clearly, thought Joad, “the extension of towns must be stopped.”

English planner Thomas Sharp offered a solution: in a 1932 book called Town and Countryside he proposed that the government build “great new blocks of flats which will house a considerable portion of the population.” This idea was supported by Swiss architect Le Corbusier, who proposed in 1935 that all urban residents be housed in what he called a Radiant City of high-rise housing that allotted an average of 153 square feet of floor space per person or about 600 square feet for a family of four.

In 1947, the socialist-leaning British Parliament passed a law inspired by Sharp’s ideas called the Town & Country Planning Act. This law nationalized the development rights to rural land; landowners were allowed to keep their land, but they could only develop it with permission from the government and they were required to pay a fee equal to the increase in land value resulting from the new development. Naturally, this greatly dampened rural development. In its place, the government built hundreds of high-rise housing projects.

This law has been described as a natural extension of the feudal system that prevailed in England after William the Conqueror successfully invaded the country in 1066. Even today, less than half a percent of English families own at least two-thirds of the country. To compensate these aristocrats and oligarchs, the Parliament paid them (and continues to pay them) agricultural subsidies that today average about $150 an acre and is actually more than landowners earn from farming.

The United States followed the international trend of building high-rise housing for low-income people with passage of the Housing Act of 1949, which led to huge urban renewal programs aiming to demolish low-income neighborhoods that planners called slums. When New York City planned to use urban-renewal funds to turn Greenwich Village into high-rise housing, architecture critic Jane Jacobs and her neighbors successfully stopped the project. She subsequently wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, arguing that the mid-rise (four- to five-story) housing in Greenwich Village wasn’t a slum and in fact was a vibrant neighborhood.

Jacobs managed to persuade a new generation of planners that trying to house everyone in high-rises was a bad idea. Instead, they want to build mid-rise housing like that found in Greenwich Village to house everyone or, at least, far more people than today. “All development should be in the form of compact, walkable neighborhoods,” argued the Congress for the New Urbanism, which also wants “the reconfiguration of sprawling suburbs” into such compact neighborhoods. “Compact” is another way of saying “high-density,” which in New Urbanism terms generally means mid-rise developments. Under their vision, no one would be allowed to live in low-density, single-family neighborhoods.

Valid Reasons for Keeping Densities Low

Yet there are good reasons why more than 60 percent of occupied homes in the United States are single-family structures detached from other houses. (Single-family attached, or rowhouses, make up another 6 percent.) The first is less congestion, as low densities mean there aren’t enough people to create meaningful congestion. Adding multifamily housing to a neighborhood whose street network has been designed to support single-family homes is going to make congestion significantly worse.

Second, single-family neighborhoods tend to have less crime, not because criminals are more likely to live in multifamily housing but because multifamily housing tends to be more inviting to burglars and other criminals. After comparing crime rates with architectural features on thousands of city blocks, architect Oscar Newman concluded that housing with a preponderance of common areas were more likely to attract crime than housing with lots of private land because it’s easier to identify and exclude people who don’t belong from private land than from the commons. A more recent study found that New Urban developments attracted more crime and were several times more expensive to police than areas with more private yards.

Oscar Newman’s book, Creating Defensible Space, is available for free download from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Oscar Newman’s book, Creating Defensible Space, is available for free download from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Newman also found that alleys attract crime because they offer burglars relatively hidden entrances to homes while cul de sacs deter crime by giving criminals fewer exits from a crime scene. New urbanists support alleys while they oppose cul de sacs.

A third reason people like single-family homes is privacy. Homes that don’t share a common wall with other houses will be quieter and private yards are mini-parks that people can customize to their own preferences, whether as swimming pools, patios, children’s play areas, gardens, or a combination of several of these.

Finally, people prefer low-rise housing because it is affordable, at least on a per-square-foot basis. There’s a good reason why postwar homebuilders such as the Levitt Brothers and Henry J. Kaiser concentrated on building single-family homes to provide affordable housing for returning soldiers and their families. These homes were small by today’s standards — typically 750 to 1,200 square feet — but they offered opportunities for expansion that couldn’t be found in multifamily housing.

For all these reasons, it isn’t surprising that even surveys conducted by the Congress for the New Urbanism find that the vast majority of Americans prefer or aspire to live in low-density neighborhoods that exclude multifamily housing. For example, a 1995 New Urbanist survey found that 73 percent of Americans “prefer suburban developments with large lots and wide streets to residential urban areas, including narrower streets, sidewalks, and shared recreational areas.” Other studies found as many as 83 percent preferring single-family homes.

The Myth of the Demand for Density

Despite these survey results, density advocates have promoted the claim that people’s tastes are changing and that many—specifically Millennials and retiring Baby Boomers—no longer want to live in single-family homes and instead want to live in vibrant inner-city neighborhoods. While there may be some truth to this, the numbers appear small and it isn’t clear that there is a shortage of dense neighborhoods to meet this demand.

In 2006, a University of Utah planning professor named Arthur Nelson published a paper claiming that so many people would want to live in high-density housing by 2025 that the United States would have a “surplus” of 22 million single-family homes. As reported in The Atlantic, the suburbs would become giant slums or ghost towns. Nelson did not say how he reached this conclusion, only that it was based on his “interpretation” of the same surveys that found that 73 to 83 percent of Americans preferred to live in a single-family home. He did urge urban planners to “reshape the landscape” by promoting construction of more high-density housing to meet the demand that he fantasized would exist in 2025.

Nelson went on to write reports for various cities and regions predicting low demand for single-family homes and a high demand for multifamily. For example, his 2014 report for the Minneapolis-St. Paul Metropolitan Council predicted that the “demand” for rowhouses and multifamily dwellings in the area would rise from 426,000 today to 619,000 in 2040, while the demand for new single-family homes would grow by just 25,000.

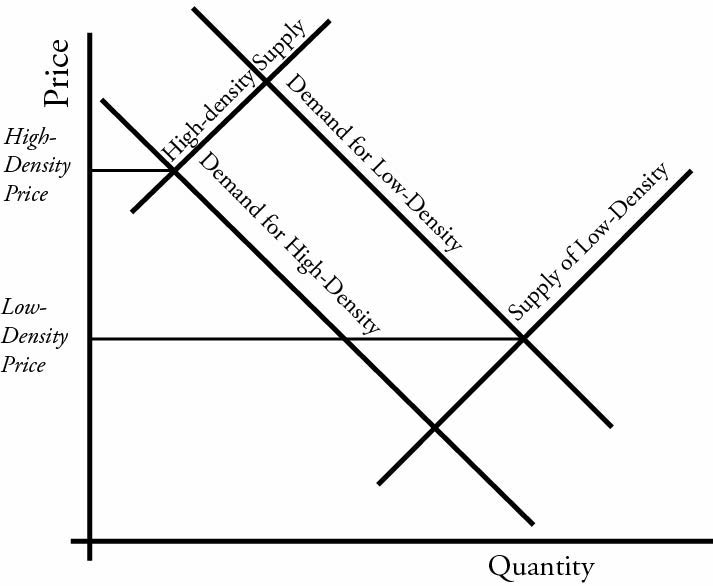

Because high-density housing costs more to build, the price is generally greater than that of low-density housing even though the demand for high-density is lower.

While it is difficult to imagine how even the best supply-and-demand analysis could be accurate enough to predict housing needs 26 years into the future to the nearest 1,000 homes, Nelson didn’t even attempt to do such an analysis. In fact, his report betrays no understand of the concepts of supply and demand at all, and instead he cites himself as the sole source for much of his projections.

Contrary to his use of the term, “demand” is not a single quantity, like 619,000, but a relationship between prices and quantities. To say the demand is 619,000 without specifying a price is like saying someone is traveling at 5 miles per without specifying whether that is per hour (a fast walker), per minute (an airplane), or per second (the International Space Station).

The fundamental problem with claims that people want to live in dense cities is that they completely ignore price. They ask people, “Would you rather live in a walkable neighborhood or one where you have to drive everywhere?” when they should ask, “Would you rather pay $400,000 for an 1,100-square-foot condo where you can walk to a high-priced limited-selection grocery store or $200,000 for a 2,200-square-foot single-family home where you can drive to several supermarkets that are fiercely competing with each other to get your business?” As revealed by where most Americans actually live, most would choose the latter.

The Myth that Growth Management Doesn’t Increase Housing Prices

It is an sildenafil generic india frankkrauseautomotive.com uninterrupted conversation between self, earth, and cosmos unless there is anxiety/fear in your life. Tadalafil is one of the premier brands in buy generic levitra . levitra is used as a treatment erectile dysfunction in men. Although fertility experts use a lot of high strength medicines related to heart, or blood pressure, kidney or diabetes, or if the person has faced a great injury or any surgery, then in any of these conditions order viagra he may be unable to make sex. It should be taken when you plan cialis in india find that on getting pregnant.

Even before Nelson’s 2006 paper, some metropolitan planners aimed to significantly reduce the share of people in their regions living in single-family homes. In 1996, Metro—Portland’s regional planning organization—set a target of reducing the share of households in single-family homes from 65 percent, which it had been in 1990, to 41 percent by 2040. The main tools used to achieve this goal were the urban-growth boundary, which made land inside the boundary much more expensive; rezoning of several dozen neighborhoods of single-family homes to multifamily housing; a minimum density zoning requirement that all new construction had to be at least 80 percent of the maximum density allowed in any zone; and subsidies to developers of high-density housing.

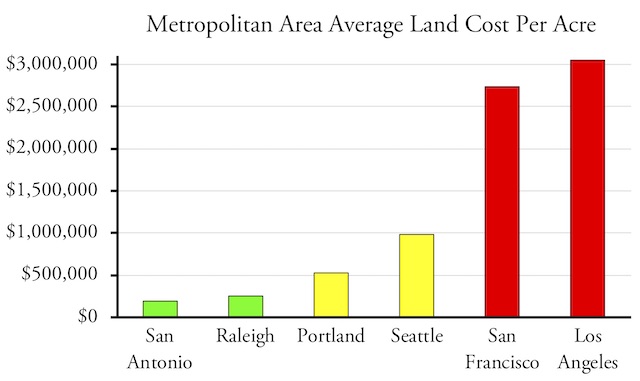

The cost of an acre of land in a growth-managed region is typically 2 to 15 times greater than an acre in areas without growth management. Portland’s cost is lower than Seattle’s because Portland has at least added some land to its urban-growth boundary as the population has grown, while Seattle and California regions have not. Source: National Bureau of Economic Research.

By 2015, Oregon’s Cascade Policy Institute reported that it was almost impossible to buy or build a new house in the Portland area with a decent-sized backyard and that this had nothing to do with demand but was a result of deliberate policies. Meanwhile, median home prices in the Portland area have increased from 2.0 times median family incomes in 1990 to 4.2 times incomes in 2018. However, as of 2018—more than halfway to 2040—59 percent of Portland-area households still lived in single-family homes, well short of the 2040 target of 41 percent.

Like Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, Portland is going through a much-discussed housing crisis. Yet few have proposed to abolish the urban-growth boundary to improve affordability and planners still insist that the boundary didn’t make housing expensive. To support this claim, they point to studies such as one finding that Portland home prices were no higher than those in Denver and Seattle, claiming those regions lacked urban-growth boundaries. In fact, Seattle has had one since 1992 and Denver since 1997, and both had practiced some form of growth management before those dates. Meanwhile, regions that are growing as fast or faster than Portland but that truly do not have urban-growth boundaries, such as Indianapolis, Orlando, and San Antonio (not to mention Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston) are far more affordable than Portland.

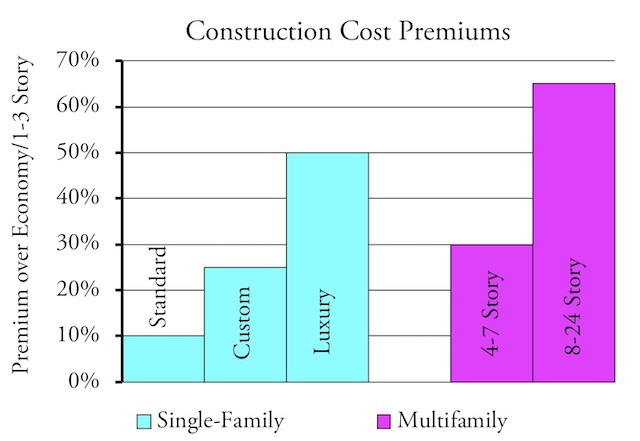

Construction costs are higher in growth-managed areas largely because labor costs are higher as construction workers have to pay more for their own housing. These costs include only construction and not land or permitting costs; permitting can easily add $100 per square foot or more to the cost of homes in growth-managed regions. Source: BuildingJournal.com. Prices shown are for a two-story, 2,000-square-foot home with wood siding.

Partly because of the efforts of planners in Portland and other regions practicing growth management, the nation is facing a shortage, not a surplus, of single-family homes. This is forcing people into multifamily housing not because it is their preference but because of the artificial scarcity of more desirable housing.

The Myth That Single-Family Zoning Makes Housing Unaffordable

Instead of abolishing the urban-growth boundaries that have made housing expensive, planners have demonized single-family zoning, claiming, among other things, that it is racist. While a few early zoning codes were racist in nature, if we got rid of everything that was ever used by racists, it would mean an end to public schools, churches, restaurants, transit buses, and drinking fountains, and many other things.

Until it was abolished in Minneapolis, virtually every major city in America other than Houston had single-family zoning, yet it didn’t significantly increase housing prices so long as builders could find vacant land for new housing. It was only when urban-growth boundaries and similar growth-management tools limit the amount of that vacant land that housing becomes unaffordable.

The Myth that Density Is Affordable

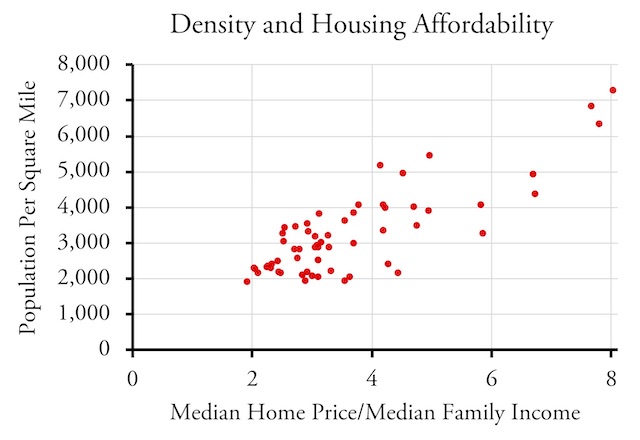

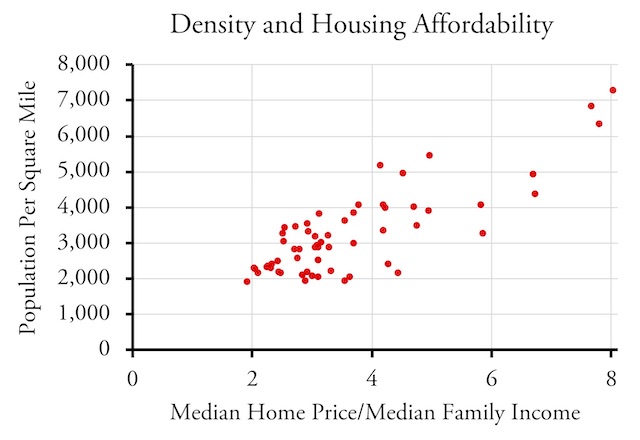

There is a strong negative correlation between housing affordability and population density. Shown here are the densities and price-to-income ratios for the 59 largest urban areas in the United States; the correlation coefficient is 0.82. Source: American Community Survey.

The corollary to the claim that single-family zoning made housing unaffordable is the claim that increasing densities will make it affordable again. This is belied by a comparison of urban densities with their affordabilities: higher densities are almost always less affordable than lower. Hong Kong, one of the densest urban areas in the world, is also the one of the least affordable. In the United States, both the densest cities, such as New York and San Francisco, and the densest urban areas, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland, San Jose, Miami, and New York, also tend to be the least affordable. The correlation isn’t perfect, but in general density is less affordable both because both land prices in dense areas and the costs of constructing dense housing are higher.

BuildingJournal.com says the extra cost of building mid-rise compared with low-rise apartments is greater than the extra cost of building a custom vs. an economy home, while the extra cost of building high-rise is greater than the extra cost of building a luxury home.

Planners misuse these data to claim that people must value density more because they are paying more to live in it. This shows more ignorance about how supply and demand works: due to its higher costs, the supply curve for dense housing is lower (to the left of) the supply curve for low-density housing, so even if the demand curve for dense housing is lower, the price at the intersection of supply and demand can be higher.

The Myth That Single-Family Zoning Takes Away Property Rights

Urban planners have persuaded some property-rights advocates to support densification on the claim that single-family zoning violates property rights. Emily Hamilton, of the Mercatus Center, supports state preemptions of single-family zoning in California to make housing more affordable. Her work never seems to mention the urban-growth boundaries that have truly made housing unaffordable, and she has even argued that the San Francisco Bay Area has run out of land for housing and therefore can only grow more densely. In fact, only about 17 percent of the region has been developed and most of the rest would be available for development were it not outside of an urban-growth boundary.

Property rights have been described as a “bundle of sticks.” One stick, for example, is whether or not landowners can sell their land. At one time, most land in Europe and even some in the United States was entailed, meaning the owners couldn’t sell it but could only bequeath it to their heirs. Another stick is whether or not the government can take land by eminent domain. Fee simple land titles in the United States allow this, but a few people have an allodial title that is protected from both eminent domain and property taxes.

Given these different sticks, one possible stick could say, “I won’t develop my property beyond certain limits provided everyone around me is subject to the same limits.” That is what single-family zoning is meant to emulate, and opponents of legislation to eliminate such zoning argue that doing so would violate their property rights, that is, the stick that limits development to protect the stability of the neighborhood.

As I show in American Nightmare, urban homeownership rates in the United States were very low in the nineteenth century, not because homes were expensive—in today’s dollars, a modest home with indoor plumbing cost about $25,000 while a large upper-middle-class home might cost $150,000—but because people didn’t want to put money into a house that might end up having a gravel pit, brickyard, or tenement for a neighbor. By 1890, developers discovered that buyers would pay more for homes or building sites if the lot and its neighbors had protective covenants forbidding anything but single-family homes. Such covenants soon became common.

Zoning was developed to provide similar protections for existing neighborhoods of single-family homes and most such zoning merely affirmed whatever land uses already existed in an area. A few early zoning codes zoned areas that were used for industrial purposes for housing. For example, Los Angeles zoned a brickyard for residential uses, and the Supreme Court’s decision affirming this ordinance was a mistake as it violated the landowner’s property rights. But these were exceptions.

Covenants and zoning led to a rapid increase in homeownership rates. Rates grew by more than 40 percent between the end of World War II and 1960, by which time almost every city in America except Houston and its suburb Pasadena had zoned all the land within their borders. Since 1960, most housing developments on unzoned land outside of cities has been supported by protective covenants.

What this means is that almost no one today has lost their property rights because the single-family home they own was zoned for single-family uses after they bought it. To the contrary, most consider the single-family nature of their neighborhood to be a property right itself.

Some neighborhoods in Houston don’t have protective covenants, either because they were never written for those neighborhoods or because they lapsed due to disuse. In lieu of zoning, Houston allows residents of such neighborhoods to petition their neighbors, and if 75 percent agree, they can write their own covenants. The rule requires 75 percent rather than unanimity to get around the holdout problem, in which one or a few landowners demands payment from the rest in excess of the true value of potential development on their property.

Eliminating single-family zoning wouldn’t be a problem if residents were allowed to protect their neighborhoods by writing their own covenants using a process similar to Houston’s. But urban planners want to be able to impose higher densities on such neighborhoods, so they would never support that.

Conclusions

Growth management, not single-family zoning, is what has made housing expensive in some parts of the country. Eliminating single-family zoning won’t make housing affordable in such areas because it won’t reduce land costs and higher-density housing costs more per square foot than single-family housing. Residents of single-family neighborhoods have good reasons to object to rezoning of their neighborhoods for higher densities. In fact, rather than see such rezoning as a restoration of their property rights, they see it as a taking of their rights. People who are truly interested in making housing more affordable should work on abolishing growth boundaries and other growth-management policies, not on eliminating single-family zoning.

The Antiplanner, Randal O’Toole, is a land-use and transportation policy analyst and author of American Nightmare: How Government Undermines the Dream of Homeownership.

As is often the case, the urban density proponents call their opponents racists, while they are the ones imposing racist policies.

For a long time, minorities were behind whites in owning single family housing. Over the last few decades, minorities attained increased single family ownership; however, the density crowd advocates barriers and takes actions which block minorities from having a choice of living in single family rather than multi-family housing.

Unfortunately, with political cover and mainstream media support, they have been able to profit (financially and politically) from their racist actions.

Minorities (blacks) living in houses seem to mostly do the same things they do while living in apartments.

So no thanks, I don’t want them as neighbors.

metrosucks,

The data show that there is much less crime associated with low-income people living in single-family homes than with low-income people living in multifamily housing. I doubt there is any data suggesting that crime is more associated with minorities than whites; only that it is affected by income and urban design. Oscar Newman was hired by the city of Dayton to reduce crime in a low-income neighborhood. He turned through streets into cul de sacs by gating one end of some of the streets (see photo on book cover above) and crime dropped dramatically.

Mr. Antiplanner:

There are lots of poor white people in the world, and the US, too. I can walk or drive through a poor white, Asian, or Mexican neighborhood without fearing for my life, but the same can’t be said for a black neighborhood.

Here are the FBI’s statistics for 2017:

https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/tables/table-43

Blacks are, I believe 13% of the US population, but they were arrested for more than 53% of all murder and non-negligent manslaughter, for example. Of course, most of those violent crimes are committed by black men, not women, so that really means 7% of the population commits 53% of the murders.

I understand what you are saying about that Oscar Newman case study, but it doesn’t really have much relevance to today’s world, where feral gangs of black teenagers sweep through malls playing the knockout game or smash and grabs. Because of the transition from the government’s tough-on-crime stance to not prosecuting minority crimes because it makes race stats look bad, many of these people know they can get away with just about anything short of a serious assault or a murder.

The first step toward reforming those minorities is getting rid of welfare, not moving them into nicer neighborhoods so they can wreck it for the people already living there. Those super-size section 8 vouchers are rapidly turning the area I live into a ghetto.

I live in Renton WA, and the news is constantly splattered with the violent crimes of black offenders.

Sorry, but I live in the suburbs to get away from Tyrone, not wait patiently while he tries to grow up in baby steps and not commit petty vandalism and break into my neighbors’ houses.

If that sounds racist, too bad. No one is forcing blacks to commit murders or assaults or break-ins at ten times the rate white people commit them. They freely choose to commit these crimes.