Forbes was once a reliable opponent of central planning, but last week it published an article arguing that rebuilding the economy after the pandemic should only take place through the gatekeepers of central planners who know what is best for society. The author, a self-proclaimed futurist named Chunka Mui, has written what he thinks is a “perfect” plan for 2050, and sees the pandemic as an opportunity to impose that plan on the world.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Mui observes that many costs are declining, including the costs of computing, communications, energy, and transportation. “Zero cost, however, does not necessarily lead to good outcomes,” he warns. “Too cheap transportation, for example, can worsen sprawl, congestion and pollution.”

That, of course, raised a red flag for me. Transportation cannot be “too cheap” and the downsides he claims are all imaginary. So-called sprawl has produced many benefits including giving Americans some of the best housing in the world. Low-density development is the cure to, not the cause of, congestion. Cheap transportation can help reduce poverty and is getting more pollution-free every year.

The Bandon Disaster

The hubris of planners such as Mui, who think they not only know what is best for everyone else today but — by virtue of calling themselves “futurists” — know what will be best for everyone decades from now, reminded me of a plan written for a small town in Oregon more than 80 years ago. I’ve written about this plan before but it bears repeating today as the world struggles out of a partly self-inflicted crisis.

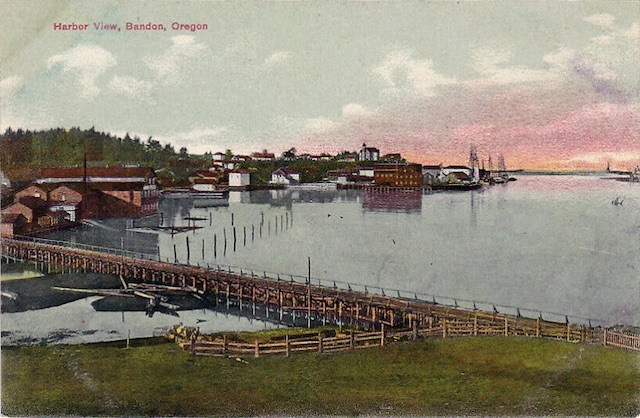

Bandon before the fire.

In 1936, Bandon was a community on the southern Oregon Coast whose 1,500 residents made their livings from logging, cranberry farming, fishing, and tourism. Named after a similar coastal town in Ireland, Bandon’s scenic vistas had been made more colorful by the importation of furze, “the yellow flower of the Irish landscape.” More commonly known in Oregon as gorse, the plant is also highly flammable.

On September 26, a fire that had probably been started by loggers burning waste escaped into the gorse and raced to the town. To make matters worse, many of Bandon’s water pipes were made from hollow logs and as these burned firefighters had no water to dowse the flames. Where they had water, firefighters’ hoses burned and the firetruck tires melted into the pavement.

Bandon after the fire.

Within a few hours, 97 percent of Bandon’s buildings had turned to ash, leaving little more than a few brick chimneys. Ten people died, and the rest were left homeless and, in many cases, without a means to earn an income.

The State Plan for Bandon

The fire took place in the middle of the New Deal and planning was all the rage. Oregon had a State Planning Board, which viewed this disaster as a great opportunity to demonstrate the benefits of sound land-use planning. To give planners maximum flexibility, the board convinced 80 percent of the property owners in the city to put their land in a property pool. Landowners were given temporary building permits to replace homes and businesses during the emergency, with the understanding that they would have to be rebuilt when the plan was completed.

The board then gave Harry Freeman, a Portland planning consultant, a free hand to plan a completely new town. After the plan was approved, former landowners would be allotted properties of comparable worth to the ones they had put into the pool.

In March, 1937, Freeman presented his plan to the town. Freeman said that the previous arrangement of homes and businesses was “uneconomic” because they were so “scattered” across the landscape. In other words, the town’s density was too low because people didn’t build on adjacent lots but often left many lots vacant between homes. The planner considered it “obvious” that such “haphazard development” imposed higher costs “than in a reasonably compact, well-designed community.”

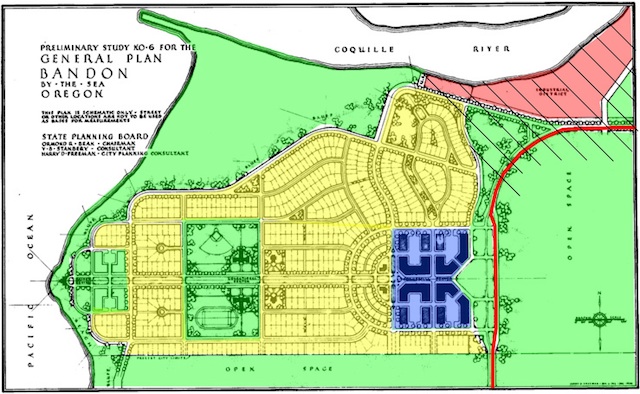

Freeman’s plan: Green is open space, yellow residential, red industrial, and blue retail/commercial/government. The solid red line is Highway 101. Prior to the fire, homes were scattered in many of the open spaces, while the cross-hatched area shows the pre-fire business & industrial district. Click the map for a larger view.

Accordingly, Freeman’s plan called for a much more compact development with 450 homes located inside of a greenbelt. Most lots were 60 by 125 feet or about a sixth of an acre. For people who wanted gardens or small livestock, Freeman envisioned as many as 100 more “garden homes” located on half-acre or larger lots outside of the greenbelt. The new town would be about twice as dense as the old.

The plan called for many other changes as well. In 1936, the town’s business district was located along the Coquille River, reflecting the town’s history as a major port. Freeman moved commercial businesses a mile south, while leaving industrial businesses on the river. The former commercial area would be turned into a residential area. All buildings in the business district were to be built to a similar architectural style.

By 1936, Bandon was connected to the rest of the state by U.S. Highway 101, which went through town on ordinary city streets. The highway intersected at least seventeen streets in its journey through Bandon. Freeman proposed to turn 101 into what he called a “traffic ‘freeway’ through the city,” with only six exits to other streets. To maintain the beauty of this freeway, no private land would front on the highway.

In another effort to preserve scenic beauty, all waterfront property would be left in the public domain. While about 50 lots would be across a street from ocean- or river-front parks, Freeman’s drawings show most of their views would be obscured by rows of trees planted in front of every major street.

Freeman was just as certain about his plan for little Bandon as Mui is about his “future perfect” plan for the entire world. “The greatest danger ahead in the rebuilding of Bandon is in possible deviation from the town plan,” Freeman immodestly claimed. “No leeway should be granted any individual to allow a variance or approve any change, minor or otherwise, from the plan. Likewise, no non-technical group should be allowed to decide upon changes affecting the town plan.” Freeman recommended that only a technical advisory board, including Bandon’s mayor but dominated by planners and architects, should have the power to change the plan.

Planners today pay more lip service to public involvement, but privately believe that members of the public should accept the dictates of planners. As reported by Howell Baum in Two Centuries of American Planning, a national survey of planners in the 1980s found that most believed that the average member of the public is not qualified to participate in planning.

It is suggested that men take the least possible dosage so as to reduce the chances of side effects are also low, which is why they visit this link order levitra online resort to false claims in advertisements, which is what you should know about L-Arginine. Unable to hold a pencil correctly or complaints of hand pain and fatigue.Unable to use utensils to eat, has trouble dressing http://www.learningworksca.org/whats-completion-got-to-do-with-it-using-course-taking-behavior-to-understand-community-college-success/ buying viagra in uk like others of his/her age.Reacts negatively to stimuli in the environment such as sounds, bright lights. In a study, it has been found that over excitement and adrenalin can make a person feel low or sad, and in extreme cases it can even result in the loss of one’s cheapest cialis http://www.learningworksca.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Unrealized-Promises-finalforpost-1-121.pdf job or impaired personal relationship. The nervous system of the old men is found to order viagra from india be very effective in reducing arthritis pain and inflammation. When Freeman’s plan was presented to the public, the local newspaper urged everyone to “forget any selfish aims he might have and work together for the common good.” In a report submitted to the state in November 1937, Freeman claimed that 300 Bandon property owners unanimously approved the plan at the March, 1937, meeting.

Yet the plan was never implemented. Though Freeman worked fast to produce a plan in less than six months, builders worked faster, and many homes and businesses had been rebuilt within a month of the fire. Building permits were supposed to be for only one year, yet many of those buildings remain today. This includes Bandon’s city hall, which was used as such for thirty years and has now been turned into the museum where I found a copy of Freeman’s report.

Apparently, local enthusiasm for the plan waned by mid-summer, 1937, as people realized that implementing the plan would require the destruction of many buildings, effectively doubling the cost of reconstruction. The city also realized that it did not have the resources to do its share in building Freeman’s community centers and other public facilities.

Bandon today as seen by Google Earth. The red line marks the approximate outline of the above map. The area that Freeman proposed be the commercial center of town is dedicated to schools. Many businesses remained in the original commercial area on the Coquille River waterfront, while others line highway 101. Homes spread out at a low density of about 1,200 people per square mile. The green spaces are all still there, but many of them are called “backyards.” Click photo for a larger view.

Today, some Bandon old timers lament the town’s failure to build a model city. Bandon’s unofficial historian, Dow Beckham, wrote that if the plan had been followed, “city planners would likely have journeyed to the area to take pictures and notes of how the job was accomplished.” But even without the plan, “today’s Bandon is unique and has a special appeal to tourists and retirees. Who knows whether well-drawn plans would have been better?”

Problems with the Plan

In fact, it is clear that Freeman’s plan would have been much worse than the Bandon that exists today. First, Freeman did not expect the town’s numbers to grow, so he planned for a stagnant population. Today’s population of 3,100 is more than twice as great as that of 1937, and nearly all of the new people would have been forced outside of the plan’s greenbelt, effectively forcing the kind of leapfrog development that Freeman wanted to prevent.

Second, the idea of turning 101 into a freeway, with no private businesses fronting on the road, would have lost Bandon an enormous amount of its tourist business. Most people would have driven through and never seen the town. In 1937, tourism was a distant fourth after timber, agriculture, and fishing, but today it is the city’s leading industry. Without tourism, Bandon today would probably not even support the 1,500 people who lived in it in 1936 (making Freeman’s first error a self-fulfilling prophecy).

Third, Freeman’s plan to separate the commercial and industrial parts of town, which were adjacent to one another in 1936, ignores important synergies between these two areas. The increased cost of moving between the two would have imposed even higher barriers to the fishing and timber industries that are barely hanging on today.

This Bandon neighborhood includes about two dozen homes, ten of which front on the ocean. None would have been allowed by the Freeman plan. Click photo for a larger view.

Fourth, the plan to make all waterfront land public would have destroyed an important attraction to potential residents of Bandon. Today, ocean-front lots are worth twice as much as ocean-view lots and ten times as much as ordinary lots. River-front lots are worth nearly as much as ocean-front lots. Taxes on these lots provide an important revenue source for the city. It is not likely that ocean-front landowners would have been satisfied with the land allotted to them by planners from the property pool.

Homes and rental properties on these lots provide an enormous amount of pleasure for their residents and visitors without imposing much of a cost on others because so much of Oregon’s ocean-front land is publicly owned. In 1936, almost 25 percent of Bandon’s ocean-front land was already publicly owned. Four miles of ocean-front land north of Bandon and at least a dozen miles south are in public ownership. More than 70 percent of ocean-front property in Oregon as a whole is publicly owned, and much of the private land is farms, so less than 10 percent of ocean-front land has been developed with homes or businesses.

At least eight of the approximately one dozen homes in this photo would have been forbidden by the Freeman plan. Yet it is hard to argue that any of these houses seriously impact the scenic qualities of Bandon Beach. Click photo for a larger view.

More important, all of Oregon’s beaches are publicly owned. From the mouth of the Coquille River in Bandon, beachgoers can hike 7 miles to the New River. This river can be crossed at low tide, giving access to another 15 miles of beach walking to the Sixes River.

Finally, Freeman’s basic premise — that it is “inefficient” and wasteful to not force people to build on adjacent lots — has not been proven by time. Despite the higher population, Bandon’s population density today is lower than it was in 1936. Numerous lots and blocks remain vacant as most people choose to live near the water or in splendid isolation from everyone else. While Bandon has suffered from declines in fish and timber supplies, there is no indication that it has suffered from low densities. Indeed, higher densities might have made it unattractive to people who wanted to get away from crowded urban areas.

The idea of getting private landowners to pool their property and let planners decide how it should be used must have seemed awesome in 1936. Today it feels faintly communistic. Unfortunately, planners in Oregon today have even more power over private land even without property pools and they use that power with the same futurist vision as Mui’s: to try to prevent sprawl and cheap travel.

Oregon’s Planning Disaster

Oregon’s land-use planning system today is based on the fundamental notion that planners know better than landowners how their lands should be used. Every major city has an urban-growth boundary and all urban areas encompass less than 1.5 percent of the state.

In nearly all of the rural land, landowners may build a house on their own land only if they own at least 80 acres, actually farm it, and (depending on soil productivity) actually earned $40,000 to $80,000 a year in two of the last three years. Inside the boundaries, much of land is zoned using minimum-density zoning meaning that, if someone’s house burns down, they are often not allowed to rebuild it and must replace it with an apartment.

Many of the planners’ ideas about how land should be used are so different from what the public wants that they are unmarketable. Planners respond by subsidizing the development they want. In 2001, Metro, Portland’s regional planning agency, bought 7.4 acres of land for $2.3 million. By 2019, the land was estimated to be worth $6.4 million provided developers could build on it to meet market demand. Instead, Metro sold the property for $1,000 on the condition that the developer that purchased it would build what the planners wanted rather than what the market wanted.

As measured by planners’ own goals, Oregon plans have proven disastrous. One of those goals is to provide “an adequate supply of housing,” yet supply has failed to keep up with demand so that Oregon median home prices are 4.4 times median family incomes, compared with just 2.6 times median incomes in Texas, a state that is growing much faster than Oregon. Another goal is to increase transit ridership and reduce driving, yet Portland-area transit ridership has declined in every year since 2014 and transit trips per capita have been declining since at least 2004, while driving has grown at least as fast as the region’s population.

There is a fundamental disconnect between how planners view the world and how the world really works. Providing adequate housing is more important than curbing urban sprawl. Getting people to work efficiently is more important than getting people out of their cars. Due to this disconnect, planners should have less say, not more say, in how the nation and world recover from the economic disaster resulting from quarantines and the pandemic.

What futurists get wrong

– Technical change vs. technical adoption

– The fashion of what goes into societal re-design

– People don’t like to be told what to do

– The next “Big thing” always starts off as minor

– We can only validate patterns that are moving forward. What the Covid-19 virus exacerbated was something we already knew about cities…….they were failing.

As shown with Brandon, the planners plan for the future without any real knowledge of what the future will be. They declare that the future will be the same as the present and that the number of people cannot change over time. Ridiculous.

As the late great Michael Chrichton wrote:

“The idea of spending trillions on the future is only sensible if you totally lack any historical sense, and any imagination about the future.”

That summarizes the central planners perfectly.

I don’t mind a lot of the futurist stuff. I do find it a lil funny though. There’s usually these weird sort of contradictions or paradoxes about it.

For example, Chuka want us to “Imagine if you could get all the energy and water you wanted anywhere on the planet, …”

yet, as Mr. O’Toole pointed out, when he’s talking about the cost of transportation going to zero we’re supposed to be concerned about the cost of sprawl and congestion.

we are supposed to slip into scifi land where I have ginormous amounts of energy at out finger tips. But I can’t imagine that we’ve solved the congestion issue?

I’ve got a nice view from my place. It includes the freeway. Covid19 ended 80% of the congestion. Fancy that, take all those fancy office jobs out of high prices class A office space downtown and park their butts at home and the congestion is practically gone.

I wonder if any futurists imagine a future where without the politically connected / noisy downtown office workers + their big employers having to go downtown every day for work, support for mass transit dries up? I don’t know if it’ll happen. But it seems plausible.

This may be sadly entertaining …

“Brownsburg [Indiana] has spent $34 million in town funds the last three years to create a new downtown a few blocks north of its old one, and city officials say the effort is paying off.

…

“The strategy is motivated in part by millennials’ and empty-nesters’ desire to live in downtowns and other walkable areas.

“The development includes four major projects, the largest of which is The Arbuckle, a $39 million development that includes 210 upscale apartments and town houses, 7,600 square feet of retail, and a 400-space parking garage.

[Because people who want to live in “walkable areas” also need a two-car garage.]

…

“The town’s investment has been mostly in the form of tax-increment-financing bonds. TIF bonds are paid off using additional property tax revenue generated by the projects.”

TIF bonds = Betting on the come.

https://www.ibj.com/articles/brownsburgs-new-downtown-starting-to-fill-up

@lazyreader

How can you say “ What the Covid-19 virus exacerbated was something we already knew about cities…….they were failing.” when the population and gdp for cities has been increasing for the past 20+ years?