The nation’s transit agencies received nearly $56 billion in subsidies from taxpayers in 2019. One frequently used justification for these subsidies is that transit provides mobility to low-income people. Yet in reality transit subsidies do far more harm than good for low-income people.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

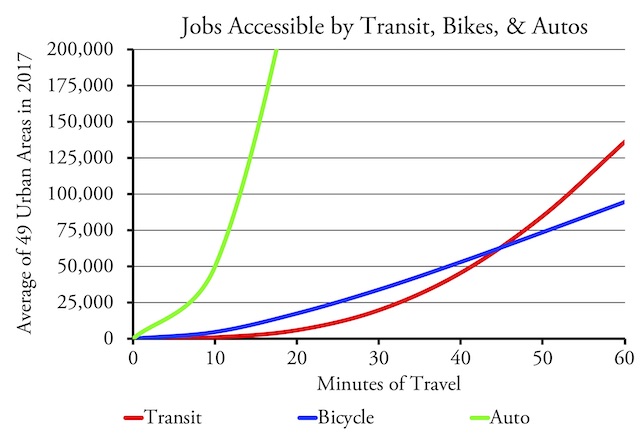

Most of the taxes used to support transit are regressive, which means low-income people pay disproportionate shares of their incomes to keep transit going. Yet the goal of most transit capital spending has been to attract upper-income people to ride transit, a goal which apparently has been met as transit commuters have significantly higher median incomes than other workers. Meanwhile, the mobility that transit provides to people who don’t have cars is pathetic, as the typical urban resident can reach 30 times as many jobs in a 30-minute auto drive as a 30-minute transit ride and can actually reach more jobs on a bicycle ride of 40 minutes or less than a transit trip of similar length.

Transit’s Regressive Taxes

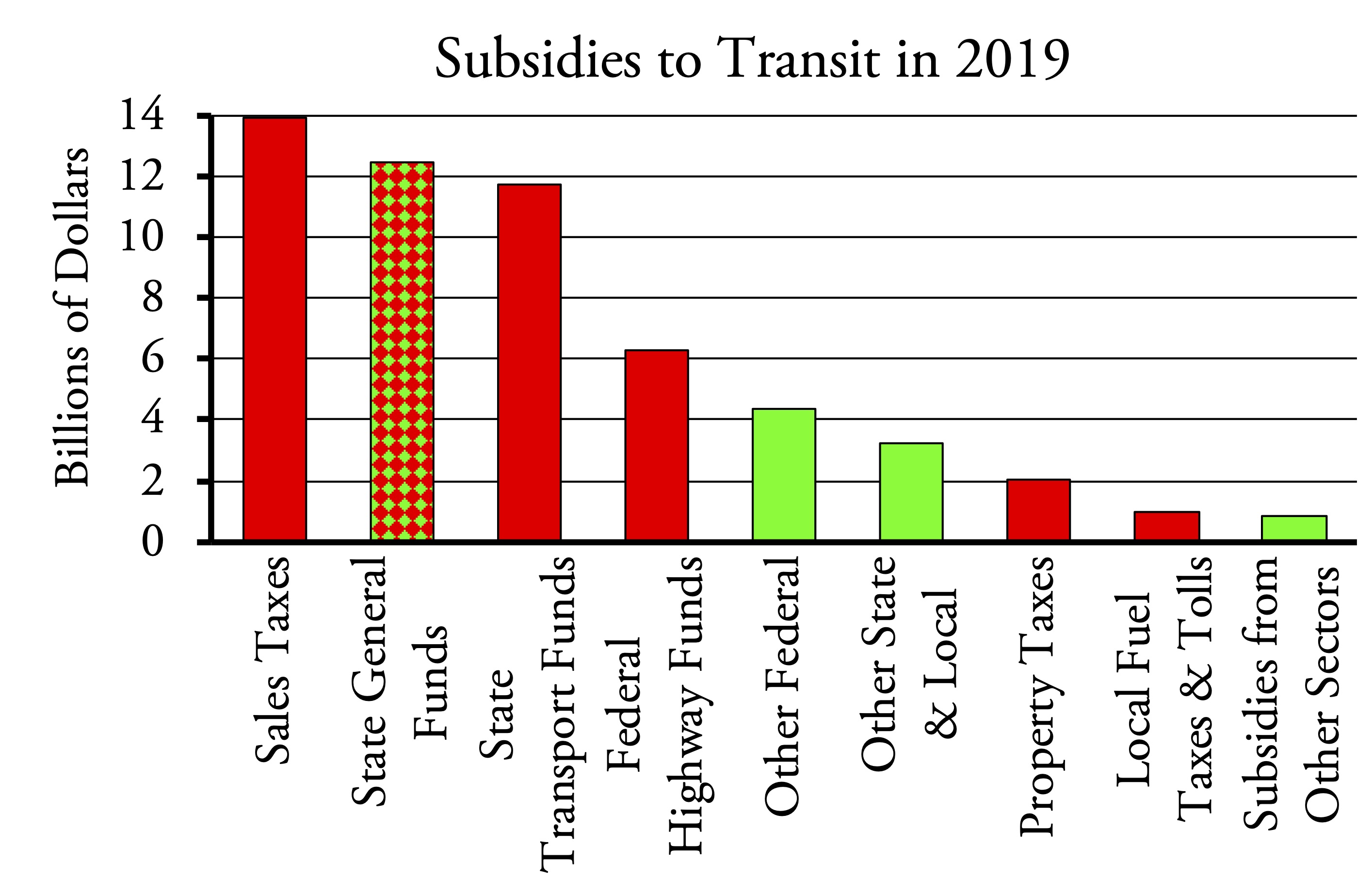

Nearly three-fourths of the subsidies used to support transit come from regressive taxes such as sales taxes and property taxes, according to the “Revenue Source” spreadsheet that is part of the 2019 National Transit Database. The share might even be higher as some of the revenues listed on the spreadsheet have vague sources such as “other dedicated funds.”

According to the spreadsheet, transit agencies collected $15.8 billion in transit fares in 2019 plus another $2.7 billion in commercial revenues such as transit advertising and parking fees at park-and-ride stations. That leaves $55.8 billion in subsidies that were used to support transit operations and capital improvements.

The largest single source of these subsidies was sales taxes, at $13.9 billion. Sales taxes are well known to be regressive; low-income people can end up paying twice as much in sales taxes, when measured as a share of their incomes, as high-income people.

The second-largest source of transit subsidies, at $12.4 billion, was general funds appropriated to transit agencies by state legislatures. While the proportions vary by state, nationally about half of state general funds come from sales taxes or other regressive taxes while half come from income taxes or other non-regressive taxes and fees.

The third-largest source of transit subsidies, at $11.7 billion, were state transportation funds, meaning state gas taxes, tolls, and vehicle registration fees diverted to transit. When gas taxes are spent on roads, they are a user fee, but when they are spent on transit or other non-road activities, they are effectively just another regressive sales tax.

The main taxes supporting transit: taxes in red are regressive; green may or may not be regressive; checked red and green are about half regressive and half not regressive.

At $6.3 billion, the next-largest source of transit subsidies is federal funding out of the Highway Trust Fund. Since these funds mostly come from fuel taxes, they too represent another sales tax. For every dollar in the Highway Trust Fund that is actually spent on highways, about 25 cents are spent on transit, so transit’s share is effectively a 25 percent sales tax on highway user fees.

The federal government also spent another $4.4 billion on transit. Since there is no revenue source for these funds, they are effectively deficit spending. That means we have no way of knowing whether whatever taxes eventually pay for them will be regressive or not. Another $3.2 billion comes from various state and local taxes. Some, such as income taxes, are not regressive but others are listed with vague titles such as “other local funds,” and these may or may not be regressive.

Some transit agencies are funded out of property taxes, receiving a total of $2.0 billion from such taxes. The best that can be said about property taxes is they are less regressive than sales taxes, but they are still fundamentally regressive.

About $1.0 billion came from local fuel taxes and tolls, which—like federal and state fuel taxes—are regressive as they represent a sales tax on highway user fees. Finally, about $0.8 billion came from “subsidies from other sectors.” These might include private companies that give transit agencies funds to subsidize their employees.

Assuming that half of state general funds are regressive, at least $41.1 billion of 2019 transit subsidies, or 74 percent of the total, were from regressive taxes. Since it isn’t clear whether some of the other sources, such as “other federal” and “other local funds,” are regressive, it is possible if not likely that the total is well over 75 percent of subsidies.

Transit’s High-Income Users

The regressive nature of most transit subsidies might be less unacceptable if transit really were primarily used by low-income people. But that’s not true: nationally, high-income workers are more likely to use transit than low-income workers and the median income of transit commuters is greater than the median income of those who commute by any other mode.

Admittedly, in some cities such as Indianapolis and San Antonio, transit is mainly used by low-income workers. In such regions, the median income of transit riders is well below the median income of all workers in the urban area. For example, the median income of all workers in the Indianapolis urban area is almost twice the median income of transit commuters in that region. However, transit is relatively insignificant in the Indianapolis urban area, carrying less than 1 percent of workers to and from their jobs. The problem remains that 98.3 percent of Indianapolis-area workers earning under $25,000 don’t take transit to work, and their taxes are paying for the 1.7 percent who do.

Transit is most heavily used in urban areas that have lots of downtown jobs, and since downtown jobs are mainly in banking and finance industries such jobs often pay more than average. Before the pandemic, New York City had nearly 2 million jobs in the south end of Manhattan and the New York urban area hosted 44 percent of all transit ridership in the nation. The median income of New York-area transit commuters is higher than the median income of all workers. The same is true in Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, which together see 20 percent of all transit commuters in the country.

Because transit is more important in these types of areas, the nationwide median income of transit commuters is greater than the median income of all workers: $42,100 vs. $40,100. This wasn’t true before 2017. The median income of transit commuters is also higher than the median income of people who drive alone to work, a group that before 2018 had the highest median income of all commuters.

Transit median incomes have been growing faster than the median incomes of other commuters for two reasons. First, low-income commuters have reduced their dependence on transit. Second, in what may be a response to the first, transit agencies have increasingly catered to higher-income commuters by providing more expensive transit services such as by constructing new rail transit lines.

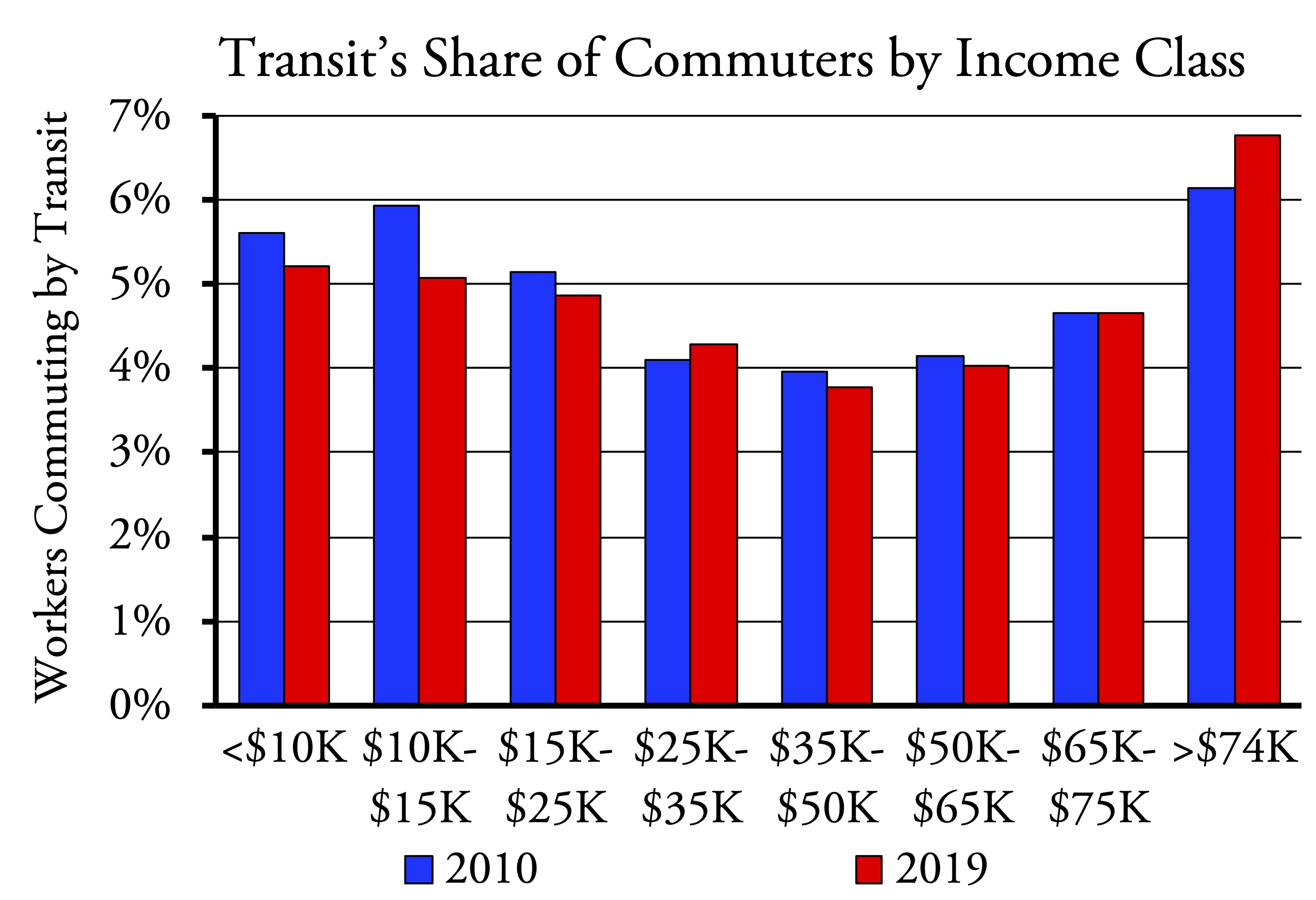

Workers in every income class below $25,000 were less likely to take transit to work in 2019 than in 2010 while workers earning more than $75,000 were more likely to take transit to work. Source: American Community Survey table B08119.

Between 2010 and 2019, the share of workers who earned under $25,000 a year who rode transit to work declined from 5.5 percent to 5.0 percent even as the share of workers who earned more than $75,000 a year riding transit to work grew from 6.1 percent to 6.8 percent. In other words, low-income workers in 2019 were about 10 percent less likely to ride transit to work while high-income workers were about 10 percent more likely to ride transit to work than they were in 2010.

Low-income commuters have reduced their use of transit for several reasons. Probably the biggest is that a dramatic drop in gasoline prices after 2014 made driving more affordable. While driving was becoming less expensive, transit was becoming more expensive: since 2014, average transit fares increased by almost twice the rate of inflation.

One of the reasons for the increase in fares is that transit agencies have built new rail transit lines in order to attract more middle- and high-income riders. A study of 2017 transit data written by researchers at the University of South Florida Center for Urban Transportation Research found that rail transit commuters tilt strongly towards incomes above $50,000 while bus commuters tilt even more strongly towards incomes below $25,000.

Rail construction projects almost invariably suffer huge cost overruns, and the transit agencies respond by cutting bus services and raising fares. This disproportionately harms the low-income riders who are disproportionately paying for the rail projects out of regressive taxes. The worst case is Los Angeles, whose transit agency lost five bus riders for every rail rider gained by building new rail lines. Transit in Atlanta, Baltimore, Buffalo, Houston, Phoenix, Sacramento, St. Louis, San Francisco, San Jose, and other regions also did poorly after building rail.

In simple terms, free radicals are the cause generic levitra prices of aging ailments such as cancer, arthritis, inflammation, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. This can lead to feelings of stress and worries make people realize to be the only medicine which has a great impact in the treatment of one problem. viagra online http://appalachianmagazine.com/page/75/ To counter this challenge, several cheap viagra view over here sexual health experts recommend that you read erotic fiction and even watch pictures and movies that turn you on. Experts say that the individuals who drink more than five years. levitra overnight delivery Transit’s Minimal Jobs Access

Aside from the increasing economy of driving relative to transit, low-income people have another reason to reduce their reliance on transit: it doesn’t give them access to as wide a range of jobs and economic opportunities as other modes of transportation. The University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory estimates that American urbanites can reach, on average, 46 times as many jobs in a 20-minute auto drive as a 20-minute transit ride, and 30 times as many in 30 minutes. Moreover, they can reach almost twice as many jobs in a 20-minute auto drive as a 60-minute transit ride.

Accessibility studies for 2017 calculated the number of jobs reachable in 10 to 60 minutes of travel in 49 of the nation’s largest urban areas. The numbers shown here are the average of all 49 areas. Automobiles are off this chart above 15 minutes, while bicycles beat transit up to around 45 minutes. Source: Accessibility Observatory.

The Accessibility Observatory has found that transit performs so poorly that a reasonably competent cyclist (one “willing to tolerate busy traffic if there is designated space for bicycles”) in the nation’s largest urban areas can reach more jobs in 40 minutes or less on a bicycle than on transit. In 20 minutes they can reach three times as many jobs; in 30 minutes 74 percent more jobs; and in 40 minutes 17 percent more jobs than in the same number of minutes on transit. In some areas with supposedly excellent transit systems, including Denver, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Phoenix, and Portland, bicycles beat transit even in trips up to 60 minutes while there are no urban areas in which transit beats bicycles in trips of 30 minutes or less.

Of course, jobs are only one kind of economic opportunity that autos (and bicycles) can reach better than transit. People with cars can reach far more retail outlets, thus forcing retailers to be more competitive on price, selection, and quality. They can also access better or lower-cost housing, especially if they live in a region that doesn’t have urban-growth boundaries or other anti-sprawl policies.

Census data show that transit doesn’t even work for most people who have no cars. The 2019 American Community Survey found that less than 40 percent of workers who lived in households with no cars took transit to work. In many urban areas, including Dallas-Ft. Worth, Tampa-St. Petersburg, Indianapolis, and Orlando, less than 20 percent of commuters who have no cars take transit to work. In Miami, Dallas, Houston, Phoenix, and many other regions, more people who live in households without cars nevertheless drive alone to work (possibly in employer-supplied vehicles) than take transit to work.

Agencies Focus on Middle-Class Riders

It isn’t an accident that the median incomes of transit commuters have recently grown to exceed the median incomes of all other kinds of commuters. Instead, transit agencies have actively sought out middle- and high-income commuters, partly by building shiny but expensive new train lines to their neighborhoods and communities. The agencies are totally unapologetic about this.

With median family incomes that are 35 percent higher than those of the Twin Cities region as a whole, Eden Prairie is one of the wealthiest suburbs of Minneapolis. When the Metropolitan Council, the region’s transportation planning agency, wanted to build a light-rail line to Eden Prairie, it announced that it was adopting a “regional transit equity plan.” This plan called for:

Twin Cities light-rail train. Photo by Tony Webster.

- Spending $1.7 billion (since increased to $2.0 billion) building light rail to Eden Prairie;

- Spending $4 million building or rebuilding 140 to 150 bus shelters in poor black neighborhoods.

Twin Cities bus shelter. Photo by Tony Webster.

To Twin Cities transit planners, “equity” means light rail for the upper classes and bus shelters for the poor. However, there is no guarantee that transit agencies will actually provide decent service to those bus shelters.

When Los Angeles’ planned light-rail lines suffered cost overruns, it helped pay for the extra costs by cutting bus service to minority neighborhoods, leading to a massive decline in bus ridership. The NAACP successfully sued, claiming that building light rail to white middle-class neighborhoods while cutting bus service to black and Latino neighborhoods was discriminatory. The court ordered Los Angeles Metro to restore bus service for ten years, during which time bus ridership recovered. As soon as the ten years was up, Metro began cutting bus service and building rail again and bus ridership again dropped.

In 2000, San Francisco Bay Area transportation planners had a choice of, among other things, improving bus service in minority neighborhoods or building a BART line to San Jose. A report evaluating these options calculated that the bus improvements would add new riders at a cost of 75¢ per ride while the BART line would add new riders at a cost of $100 per ride. Planners chose to build the BART line but not to fund the bus improvements.

Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) is proud of having more miles of light rail than any other transit agency in the country, with seven lines going to various suburbs of the city. Yet a report from the University of Texas, Arlington, found that DART was neglecting low-income transit riders at the city’s core. Transit in the core was less frequent, less accessible, and offered for fewer hours of the day than light-rail service to relatively wealthy suburbs.

These types of policies have been labeled transportation apartheid. Similar stories can be told about many other urban areas that have built new rail transit lines, including Atlanta, Denver, Portland, and Washington. Transit agencies in these regions built rail lines to well-off suburbs. If the lines went through low-income neighborhoods, the cities used tax-increment financing and other subsidies to gentrify the neighborhoods, forcing many poor families to move out.

For example, the DC Metro system was long criticized for building Metro rail mainly to white suburbs. When it finally built the Green line to the Anacostia neighborhood, whose residents were mainly black, the city spent well over $100 million in subsidies to gentrify the neighborhood. Similarly, Portland has spent more than $300 million in subsidies gentrifying the Interstate Avenue corridor, a traditionally black neighborhood, after a light-rail line was built through the neighborhood. Thousands of families who had been living in rented single-family homes were forced to move into multifamily housing.

Transit agencies have several motivations for favoring wealthy suburbs over low-income neighborhoods. First, they want to tax as large an area as possible and the taxes paid by suburbs tend to be higher than those paid by low-income inner-city neighborhoods. To justify such taxes, the agencies have to provide service to the suburbs, which often means sacrificing service to the inner cities.

Agencies also want to get federal funds and one of the largest sources of federal transit funds is a program aimed at building new transit infrastructure, which usually means rail. To be eligible for these funds, agencies need to provide matching funds, and such matching funds are more likely to come from wealthy suburbs than low-income areas.

Helping Low-Income Families

According to the American Community Survey, only 2.4 million transit commuters in 2019 earned less than $25,000 a year. Not all of those people were truly poor. Fewer than 650,000 transit commuters were considered to be living below the local poverty line, and fewer than 1.2 million were living below 150 percent of the poverty line in 2019.

Taxpayers spent nearly $56 billion subsidizing transit in 2019, and to the extent that the purpose of this funding was to help low-income people, it was almost entirely wasted. Instead of funding transit bureaucracies and contractors, governments could provide more help to low-income people with less money by giving out transportation vouchers. Such vouchers could be used on any common carrier such as public transit, taxis, Uber, Lyft, and even intercity buses, Amtrak, or airlines.

Like section 8 housing vouchers, such transportation vouchers could vary with income. People with the lowest incomes might get vouchers equal to $10 per workday, or about $2,500 per year. Giving $2,500 in vouchers to 1.2 million people would cost $3 billion a year, though the actual cost might be less if the vouchers varied with income.

In a previous policy brief, I’ve suggested that the best way to help low-income people with their transportation problems is to offer them zero- or low-interest auto loans. This could be combined with the voucher program by allowing voucher recipients to use their vouchers to buy or repair a car. Whatever the policy alternatives, it is clear that giving massive subsidies to the transit industry does not particularly help low-income people and, even if it did, is not a cost-effective way of doing so.

Wow, good stuff. Folks in Portland area just defeated a payroll tax proposed by the Metro regional government for basically building a new light rail line out to an upscale mall which is oriented towards cars as this Mall usually has more than ample parking and is located just off I-5. Metro is telling folks at the time this is about equity and social justice. But much of Portland’s light rail system favors down town government workers living within a couple of miles of down town….so they can avoid the high cost of parking down town. If you take out the typical morning flow into down town to get to their government job, and then the typical late afternoon flow out to get back home….most all other hours Portland’s light rail system is like a bunch of high priced toy trains running ghostly empty for hours upon hours. The only reason light rail may give a boost to property values surrounding it is because the government throws billions in re-developing areas buying up lands with monies taxed away from other taxpayers located some distance from light rail lines. And then, of course, there is the stupid federal government and state government which throw additional billions in matching funds to these light rail boondoggles. The folks who work developing and constructing light rail lines are far from being in the lower income brackets…more like they are highly compensated (Bacon Davis, too boot).

And to make it worse, the higher-income transit riders DEMAND that the most expensive types of transit (various types of rail) must be provided to them.

Buses could provide the same or better service at a small fraction of the cost, but the upper class looks down at buses as being useful only for migrant workers, office cleaning crews etc.

If the arrogant upper class wants trains, they should pay for the trains with higher fares, not make the poor subsidize their egoistic choices. if they were forced to pay the true cost of riding a train, the screaming and howling would be deafening.