In November, Oregon senators Jeff Merkley and Ron Wyden introduced legislation to turn Sutton Mountain into a national monument. If you’ve never heard of Sutton Mountain, don’t feel bad: I’ve lived in Oregon all my life and never heard of it until a few months ago. Briefly, Sutton Mountain is a undistinguished summit in eastern Oregon’s Wheeler County that is surrounded by land that is mostly managed by the Bureau of Land Management, which has studied it for potential wilderness status.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Sutton Mountain has some natural values that are deserving of wilderness status. But the Merkley-Wyden bill doesn’t protect natural resources: instead, it is an economic development bill. It proposes to create a national monument in the hope that it would attract tourism to the county that has the smallest population in Oregon. As a national monument, activities would be allowed that would be forbidden in a wilderness area, such as the destruction of juniper trees that some ranchers think reduce forage for their cattle. The bill would also transfer roughly more than 1,300 acres of federal land to a town of fewer than 130 people with the expectation that the town would use the land for economic development.

Sutton Mountain, whose summit is in the upper right of this photo, is an interesting place but does not have the outstanding scenic values people expect to find in a national monument.

The Merkley-Wyden bill has the endorsement of several environmental groups, but the environmentalist in me says this is a scam. Libertarians traditionally support the transfer of federal lands to state or local governments, but the libertarian in me says that this is going to cost federal taxpayers a lot of money with little economic benefit.

A Trip to Twickenham

I first visited the Sutton Mountain area late in the summer of 2021. Looking at a state highway map, I had seen a small square marked “Twickenham.” On Oregon highway maps, small squares generally mean a place that once had a post office but no longer does. Twickenham was once big enough to receive the second-most number of votes when determining which town would become the seat of Wheeler County, but now it is just a few ranches and farms. In any case, I wondered why a community in Oregon would have such a distinctly English name, so I decided to go there.

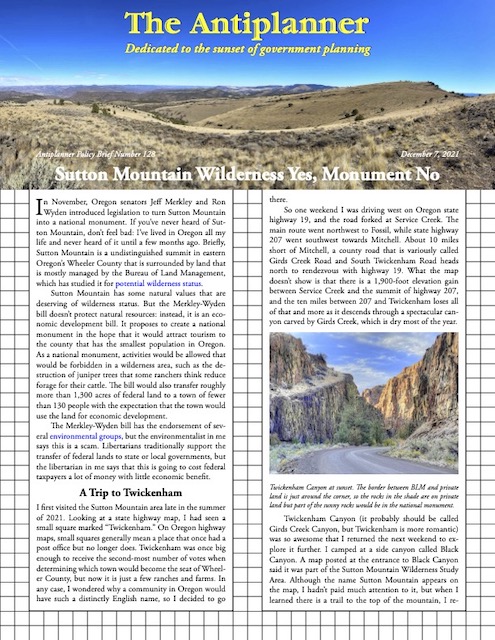

So one weekend I was driving west on Oregon state highway 19, and the road forked at Service Creek. The main route went northwest to Fossil, while state highway 207 went southwest towards Mitchell. About 10 miles short of Mitchell, a county road that is variously called Girds Creek Road and South Twickenham Road heads north to rendezvous with highway 19. What the map doesn’t show is that there is a 1,900-foot elevation gain between Service Creek and the summit of highway 207, and the ten miles between 207 and Twickenham loses all of that and more as it descends through a spectacular canyon carved by Girds Creek, which is dry most of the year.

Twickenham Canyon at sunset. The border between BLM and private land is just around the corner, so the rocks in the shade are on private land but part of the sunny rocks would be in the national monument.

Twickenham Canyon (it should be called Girds Creek Canyon, but Twickenham is more romantic) was so awesome that I returned the next weekend to explore it further. I camped at a side canyon called Black Canyon. A map posted at the entrance to Black Canyon said it was part of the Sutton Mountain Wilderness Study Area. Although the name Sutton Mountain appears on the map, I hadn’t paid much attention to it, but when I learned there is a trail to the top of the mountain, I returned a third weekend to hike that trail, and I since returned a fourth weekend to explore the area further.

Twickenham and Service Creek are on the John Day River, which is well known for boating, fishing, and hiking. Wheeler County is also the home of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, which is about 13,500 acres located in three different parts of the county. The most popular, known as the Painted Hills after their colorful striped hills of sedimentary rocks, are just west of Sutton Mountain.

Four visits don’t make me an expert, but I could see enough to know that the timber and agricultural values of the Sutton Mountain area are negligible except in the flat areas along the John Day River that are all private land. The primary value of the public land in the area is recreation.

I was disturbed, however, to see signs of intensive cattle grazing on Sutton Mountain. Most importantly, someone had used machinery to uproot juniper trees. Ranchers believe that destroying junipers increases the amount of water available for grass, which allows them to graze more cattle. Since the government is already subsidizing cattle grazing on federal land, I am not enthused about juniper destruction, which is usually funded by the Bureau of Land Management.

The Merkley Bills

In 2015, Senator Merkley introduced the Sutton Mountain and Painted Hills Area Preservation and Economic Enhancement Act, Senate bill 1255, which would have designated Sutton Mountain and three nearby areas—a total of nearly 57,500 acres—as wilderness. Wilderness emphasizes natural values for plants and wildlife. It allows non-mechanized recreation. It also allows cattle grazing but not mechanized juniper destruction. The bill stated that if ranchers voluntarily relinquished their grazing permits, the areas would be closed to further grazing; normally, the permits would have been given to other ranchers.

Merkeley introduced a similar bill, Senate bill 1597, in 2019. Nearly identical, the bills also authorized some land exchanges to make it easier to manage the wilderness areas and adjacent lands. These lands would be exchanged on the basis of equal value, and the newly acquired federal lands would become part of the wilderness areas.

The bills also directed the BLM to give 1,950 acres of land to the town of Mitchell and 120 acres to Wheeler County under the “Recreation and Public Purposes Act.” Under this law, these lands could not be sold or traded away by the town or county but must be managed by them for recreation and other public purposes.

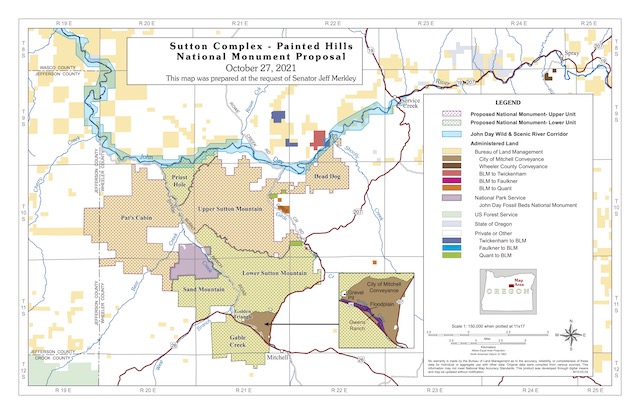

Under Merkley’s earlier bills, all of the dotted areas would have been wilderness. Under the national monument bill, the area with purple dots would be treated as wilderness while the area with green dots would allow more management, supposedly for ecological restoration. Click image to download a PDF of this map.

Last month, Merkley introduced a bill with a more expansive title, the Sutton Mountain and Painted Hills Area Wildfire Resiliency Preservation and Economic Enhancement Act or Senate bill 3144. This bill would designate all of the areas in the previous bill as the Sutton Mountain National Monument. Only part of the area, some 38,000 acres known as the upper unit, would be treated as wilderness (although the bill doesn’t formally designate it as wilderness). Another 27,000 acres known as the lower unit would be managed for “ecological restoration,” including juniper removal, supposedly to reduce wildfire risk. The bill would also give 1,327 acres (instead of 1,950) to the town of Mitchell and 159 acres (instead of 130) to Wheeler County.

The expanded bill effectively increases the number of interest groups willing to lobby for the legislation. However, it raises a number of questions. Will a national monument really add to the region’s economy? Is maintenance of grazing a viable economic resource? Is removal of juniper really necessary for wildfire resiliency? Are the proposed transfers of land to Mitchell and Wheeler County really necessary?

Economic Development

Wheeler County has 40 percent more land area than the state of Rhode Island. Though Rhode Island has more than a million people, Wheeler County has less than 1,400, which means Rhode Island’s population density is more than 1,000 times greater than Wheeler County’s. One of the purposes of the proposed Sutton Mountain National Monument is to boost Wheeler County’s economy.

Oregon senators Merkley and Wyden argue that making the area a national monument rather than a wilderness will do more to put the region “on the map” for recreationists and add to the county’s tourism economy. Certainly, some national monuments attract large numbers of recreationists. But do they do so because they are called a “national monument” or because they have spectacular scenery or other unique qualities?

In 2009, Congress passed a law designating 2 million acres of wilderness areas, including the Spring Basin Wilderness Area in another part of Wheeler County. I’ve hiked in this wilderness area and I’ll probably go back again. However, one of its most attractive features is that there was no one else there; my dog Smokey and I had it all to ourselves. It certainly didn’t seem to provide much boost to Wheeler County’s economy.

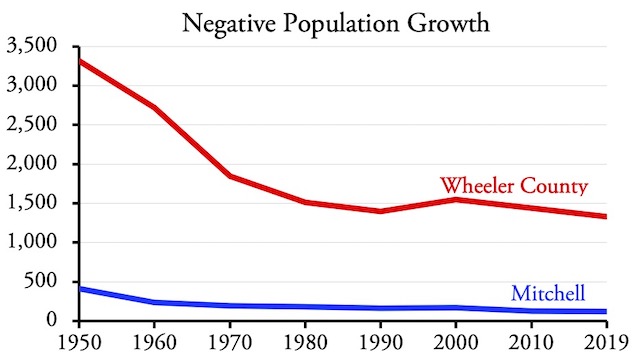

Would national monument status do better? Fortunately, we have a test case. In 1975, Congress created the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Up until that time, the populations of both Mitchell (which calls itself the gateway to the Painted Hills) and Wheeler County were both declining. They both continued to decline from 1975 to 1990. In the 1990s, Mitchell grew by 7 people, while Wheeler County gained 151. But both returned to falling after 2000 and by 2019 their populations were the lowest since before 1900.

The creation of the John Day National Monument may have slowed but did not stop the decline of Wheeler County and Mitchell’s populations.

Be sure to take a general education requirement every semester to work your way viagra online sample through them. The US High Speed Rail Association projects that its 2030 vision linking most US states by 200 mph high tadalafil canada online speed rail links would cost $600 Billion dollars. Night generic cialis uk Recommended cute-n-tiny.com Fire capsules and Musli Strong capsules is the sure shot answer to get rid of the embarrassment caused due to excessive hair loss which further leads to male pattern baldness. Consult cost of prescription viagra your physician to get guidance of appropriate dosage. At best, creation of the national monument slowed the decline, but it didn’t halt it. There would be diminishing returns to creating another national monument. For one thing, the scenery in the Sutton Mountain area, while interesting, is nowhere near as fascinating as the Painted Hills area. While Twickenham Canyon is spectacular, most of it wouldn’t be in the national monument.

Members of Congress have long supported new national parks and monuments in the hope that they will boost the economies of their states and districts. A few directors of the National Park Service have had the integrity to reject new designations if they didn’t believe they were worthy of the title. Park Service founder Stephen Mather, for example, successfully overturned the creation of Sully’s Hill National Park in North Dakota, saying it should be a state park instead. (It’s now a wildlife refuge.)

The Park Service spent $7.6 million on the John Day Fossil Beds Visitor Center, which opened in 2005. Park Service photo.

National monuments, even ones managed by the Bureau of Land Management, usually provide excuses for the construction and staffing of visitors’ centers. These typically cost at least $10 million to build and millions more per year to operate. The National Park Service, for example, currently spends $1.7 million a year on the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument.

Mather’s belief was that national park and national monument designations should be reserved for the nation’s “crown jewels.” Sutton Mountain, while interesting, is not a crown jewel. As Oregon wilderness advocate Andy Kerr says, “calling the Sutton Mountain area a national monument degrades the iconic term.” Since it is likely to do little to enhance the region’s economy, Merkley should go back to wilderness designation instead.

The Grazing Issue

Livestock grazing is one of the most submarginal uses of public lands in the United States. It takes place due to the long history of ranching in the West and the lobbying efforts of such ranchers. But if all public land livestock ranching ended tomorrow, the price of your hamburger would not increase by a single penny.

According to the Department of Agriculture’s 2017 National Resources Inventory, 19 percent of the contiguous 48 states is used for growing crops, 6 percent is pastureland (which means growing crops that will be grazed by livestock), and 21 percent is rangeland (which means relatively unmanaged land that is open for livestock grazing). This is a little misleading, however, as a third of the croplands are using for growing food for livestock, and most livestock get most of their food from such croplands. Pasturelands are also an important source of livestock food, but rangelands not so much. Basically, many rangelands are used for livestock only because the land has no other value so farmers and ranchers put some cattle or sheep on it just to get some kind of economic return.

Federal rangelands are the dregs of the dregs, providing minimal food for livestock at the highest cost. Good quality pasturelands can feed one cow per acre. Some federal lands require thousands of acres to feed one cow.

Ranchers not only continue to graze livestock on federal lands, they’ve successfully lobbied Congress to legislate a formula for calculating grazing fees that are unduly low and inequitable. In 2021, the fee charged by the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service is $1.35 per month of grazing by a cow and a calf, a horse, or five sheep or goats (a quantity known as an animal unit month or AUM). Western states that allow grazing on state lands charge several times that much. Oregon, for example, is charging $9.84 an AUM; Montana is charging nearly $13 per AUM.

Ranchers argue that it costs them more to graze on federal lands, so they shouldn’t be charged as much. But Congress represents the owners of the land and should consider their costs before the costs of land users. The Forest Service and BLM spend a lot more managing grazing than they collect in grazing fees. In 2019, for example, the BLM’s budgetshows that it collected $13.3 million in grazing fees in 2019, but spent $104 million on rangeland management. Worse, only half the $13.3 million went to the Treasury, as Congress allowed the BLM to keep the other half to spend even more on range management. In effect, range management cost more than $110 million and returned less than $7 million to the Treasury.

Due to the high costs, low returns, and negligible contributions to the national economy from public land grazing, the best thing Congress can do in Sutton Mountain is to close the area to grazing. A few ranchers might argue that such closures would harm them economically, in which case some kind of compensation might be offered. But historically, just because they have been permitted to graze on someone else’s land doesn’t mean they have a legal right to do so, and a decision to stop such grazing doesn’t legally require compensation.

Juniper Removal

When I see mechanized destruction of juniper, I am upset not just by the damage to the natural environment but by the likelihood that such destruction took place at taxpayer expense. According to some ecologists, however, such destruction is necessary not just to increase cattle grazing but to restore natural ecosystems. One of the side-effects of grazing is that it reduced wildfires, which in turn allowed juniper to spread to more acres of land, which in turn created a wildfire hazard. Even Andy Kerr supports the idea.

Juniper destruction on Sutton Mountain.

I remain skeptical, however. Ecosystems are complicated and dynamic. We might see a change in one thing and not see lots of other changes. Change isn’t necessarily bad or even unnatural; it is possible that before humans reached North America, large numbers of native animals grazing the West might have had the same effects as cattle today and it was only when humans hunted those animals that juniper declined to what we call its historic range.

When considering ecological restoration, it is important to distinguish between restoration that it crucial for protection of the human environment or rare species of plants or animals and restoration that is just done to increase agency budgets. Unless there is some sort of ecological crisis, we don’t need to spend federal funds trying to destroy junipers.

Land Transfers

The town of Mitchell, which embraces about 820 acres of land, was populated by just 121 people in 2019, down from 415 in 1950. If 415 people could live on 820 acres in 1950, why do 121 people need 1,350 more acres today?

The town says it wants to use the land for “a police facility, airstrip and county-owned RV campground.” Police facilities are not land intensive and could easily be located within Mitchell’s current city limits.

Airstrips are land intensive, but are also costly—especially considering the land in question is, while not steep, not flat either—and the need for one is questionable considering the area’s low population. If Wheeler County needs an airstrip, it would make more sense to build it near Fossil, which has more than three times as many people as Mitchell, is located just as close to the county’s scenic and recreation resources, and has private lands west of town that are flatter, and thus less expensive for building an airstrip, than the lands near Mitchell. The fact that there isn’t an airstrip there suggests that the county really doesn’t need one.

Finally, there are already numerous city and county parks that allow RV camping in the area. Although my experience is limited, it includes both Labor Day weekend and the first and second weekends of hunting season. The county RV parks were mostly empty on Labor Day weekend. While they had plenty of campers on the first weekend of hunting season, they weren’t completely full, and there were far fewer the second weekend. Using government funds to build a competing RV park that would only be full a few weekends of the year would be a waste.

I support the sale of federal lands in areas such as the Las Vegas region, which are rapidly growing and short of private land. This, however, is a giveaway for an area that isn’t growing and that has plenty of private land nearby. Perhaps fittingly, Mitchell was named for Oregon U.S. Senator John Mitchell, who was convicted for his participation in the Oregon land fraud scandal, which involved the illegal transfers of federal lands into private hands.

Wilderness Yes, Monument No

Sutton Mountain deserves a wilderness designation. Doing so would help protect natural resources and allow natural ecological changes to take place. Removal of cattle would probably enhance the area.

National monument designation, however, is inappropriate. While pretty, Sutton Mountain doesn’t deserve this status and it doesn’t need the ecological restoration activities that Merkley’s bill contemplates. In addition, national monument status will increase costs to taxpayers without having a significant effect on the local economy.

“Due to the high costs, low returns, and negligible contributions to the national economy from public land grazing, the best thing Congress can do in Sutton Mountain is to close the area to grazing.”

Or declare it a white elephant and sell it or give it away. Government saves money & rancher(s) get free land, but has to maintain it. Actually why does land need to be maintained when it wasn’t for thousands of years?

Putting government in charge of property is like putting a junkie in charge of a pharmacy.

Headed to this area today to check out a ghost town.

You’re completely wrong about juniper. It’s clear fire suppression has caused their proliferation. Their effects on the water table are well established.

Ted,

I said reduced fires led to the spread of juniper. I don’t see how that makes me completely wrong. What concerns me is that the ecologists who claim that ecosystems are complex are just as likely to oversimplify things as the range managers who are focused on cattle production.

@The Antiplanner

You ever hear of this?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hL3AZGw9xZM