In the mid-1990s, the United Kingdom privatized its government-owned railroads. That privatization proved to be a disaster, and now the country is renationalizing the trains.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Except none of these things are true. Britain didn’t really privatize its railroads in the 1990s. What it did do turned out to be pretty successful but, like many transportation systems, failed to survive the pandemic. What it’s doing now isn’t really nationalization but merely rebranding of the system—in effect, rearranging the deck chairs.

What’s really happened is that the country has been groping around for more than a century with failed government policies interfering with the railroads when what it should have been doing is leaving them alone.

1921: The Big Four

To understand British railways, we have to go back to 1920, when Britain—England, Scotland, and Wales, which have less land area than the state of Kansas—had 120 different railroads, many of them competing fiercely with one another. Some of these companies were highly successful, while others were losing money.

Today, people understand that competition leads to innovation, increased worker productivity, and both increased value and lower costs for consumers. But in 1920, it was widely believed that business competition did more harm than good. The word “competition” was often preceded by the word “ruinous,” because it was assumed that companies would be forced by competition to reduce their rates and the quality of their service until they went out of business.

One person who believed this was Eric Geddes, who was make the U.K.’s Minister of Transport in 1919. A former railway executive, he believed that monopolies would be better for investors and workers. He persuaded Parliament to pass the Railways Act of 1921, which forced the consolidation of nearly all of intercity railways in England, Scotland, and Wales into just four companies, which became known as the Big Four.

Crudely, the act divided the nation into quarters with London being at the center of the divisions, and all the railways in each quarter were merged into one that would have a near monopoly in its region. Urban railways such as the London underground were exempted as were light or narrow-gauge railways, which were mostly under 20 miles long. Since London is in the south end of the nation, the quarters were not of equal size, and the four railroads ranged from fewer than 2,200 route miles to more than 7,000 route miles.

The London & North Eastern Railway never made money, but it designed a locomotive, the Flying Scotsman, that set records for being the fastest steam engine in the world. Photo by Brent James Pinder.

Merging money-losing companies with money-making companies provides no assurance of long-term profitability, and the four merged companies were never very profitable. In fact, the second largest of the four, the London & North Eastern, never earned a profit in its entire life.

1947: Nationalization

When Britain nationalized its railways in 1947, it wasn’t due to concerns about profitability or the adequacy of service. Instead, the Labour government had a socialist belief that government ownership of all industries was a good thing. Canals, ports, bus companies, and trucking companies were also nationalized, as were many other industries, including coal, steel, electricity, gas, and telecommunications.

This British Railways steam locomotive was built in 1954, many years after most U.S. railroads began converting to Diesels. Photo by Hugh Llewellyn.

Initially, British Railways was profitable, but it was able to earn a profit only by not updating its aging infrastructure and obsolete equipment. For example, it relied almost exclusively on steam locomotives until the late 1950s, by which time American railroads had almost completely replaced steam with Diesels.

In 1955, British Railways asked the government to spend £1.24 billion (about $38 billion in today’s money) in a major modernization program, including electrification of some lines and Dieselization of the rest, construction of new freight yards, and new passenger equipment. This program turned out to be a disaster. A buy-Britain requirement forced British Railways to purchase new locomotives from local companies that had little experience manufacturing them, leading to poor designs and maintenance problems. Trucks were capturing most freight haulage and the new freight yards proved to be largely unneeded. As a result, the state-owned company’s losses grew to £42 million in 1960, equal to about $1.3 billion in today’s dollars.

In 1963, British Railways published a report sadly noting that 30 percent of its system carried just 1 percent of its traffic and a third of its passenger cars were used fewer than 18 times a year. These cars cost money to maintain yet earned almost no revenue. In response, the railway shut down a third of its passenger network and closed more than half of all its train stations. Naturally, this was highly controversial.

1993: A Weird Sort of Privatization

Despite these cuts, losses continued to grow. Despite continued government subsidies, passenger traffic continued to decline. In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher popularized the term privatization by privatizing coal, steel, telecommunications, British Airways, ports, and other industries, but it wasn’t until her successor, John Major, was in office that the country dealt with the railroads. The problem was how to do it.

Advocates of privatization within British Rail wanted to create a nationwide private monopoly while Major himself wanted to return to several regional monopolies resembling the Big Four. Instead, the Railways Act 1993 made the unusual and, in retrospect, mistaken decision to separate rail infrastructure from rail operators. It privatized all the infrastructure as one railroad unoriginally called Railtrack, which wouldn’t operate any revenue trains. Instead, the trains would be operated by 25 franchisees, most of which were guaranteed monopolies over the routes they operated. The franchisees paid Railtrack fees that were to be used to maintain and upgrade the rail lines.

The Labour Party bitterly opposed privatization and vowed to reverse it as soon as it took office. But when Tony Blair became prime minister in 1997, he did so as a centrist, and left the private railroad system in place.

The Hatfield train crash in 2000 killed four people and was blamed on poor maintenance and incompetent Railtrack administration. This led the government to renationalize rail infrastructure while keeping the franchise system of rail operators. Railtrack was replaced by Network Rail, which—like Amtrak—is a state-owned corporation.

Many foreign companies are among the franchisees that operated British passenger trains. This train was run by Abellio, a Dutch company. Photoby Geof Sheppard.

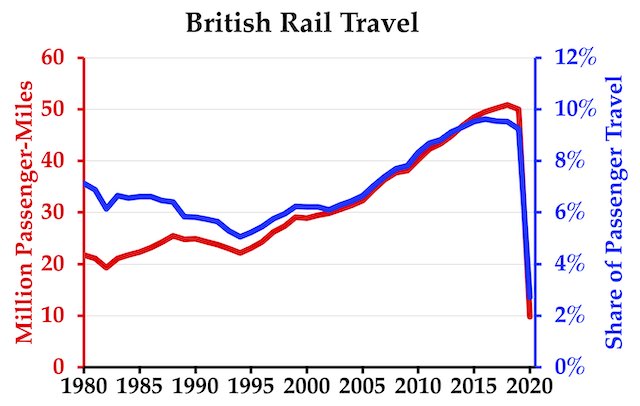

One of the things that kept the franchise system politically viable was its great success. While government-owned passenger railroads in every European country on the continent except Switzerland were losing market share to highway travel, Britain’s rail market share under franchising was growing, rising from 5 percent of ground transport in 1994 to 10 percent in 2015. Nevertheless, Jeremy Corbyn, a socialist who became leader of the Labour Party in 2015, attacked the system whenever he could.

For example, in 2016, Corbyn released a video showing him sitting on the floor of a train because, he said, all of the seats were taken. He blamed Virgin Rail for not providing enough seats and claimed this demonstrated that the trains should be renationalized. In response, Virgin Rail released video showing that Corbyn had walked by many vacant seats before sitting on the floor and passengers on that route told reporters, “I’ve never once not got a seat.” Corbyn later admitted that he bypassed the empty seats because he wanted two empty seats so he could sit with his wife.

Both rail travel and rail’s share of travel had been declining prior to Britain’s semi-privatization, but both showed remarkable growth after 1995. Source: British Department for Transportation.

Despite the success in growing ridership, the franchise system was not a success in saving taxpayers’ money. Franchises were distributed based on bids, and bids could be negative. Franchisees that managed popular trains paid the government money; franchisees of less popular routes were paid by the government to keep the trains running. The net was about zero, but that was before the costs of maintenance and improvements were counted.

Network Rail spent a lot of money each year on maintenance and improvements that was never recovered from franchisees. In 2019, government subsidies to Network Rail amounted to £4.1 billion (about $5.5 billion in today’s dollars).

Nor was it ever shown that Network Rail was more competent than Railtrack. If the Hatfield train wreck was the defining moment for Railtrack, the great Timetable Disruption of 2018 was the defining moment for Network Rail. Network Rail had electrified and made other improvements to some rail lines, then gave franchisees notice of the changes in schedules they would have to make because of the improvements.

Normally, franchisees were given sixteen months’ notice to plan for changes in timetables, but in this case, it was just a few weeks. The franchisees were unable to train enough drivers to handle the new locomotives on new timetables in that amount of time, and as a result were forced to cancel as many as two out of three trains on some days in May 2018. The problem was caused by Network Rail, but as the public face of the railroads the franchisees were given much of the blame.

Although the franchise system had its critics, it produced significant benefits for rail travelers. Between 1995 and 2019, passenger ridership and passenger-miles both increased by more than 115 percent. The number of trains per day had increased by a third. Public satisfaction with the railways also increased, at least prior to the 2018 timetable disruption. Over the long run, the U.K. and Switzerland were the only countries in the world where train travel was growing faster than highway travel.

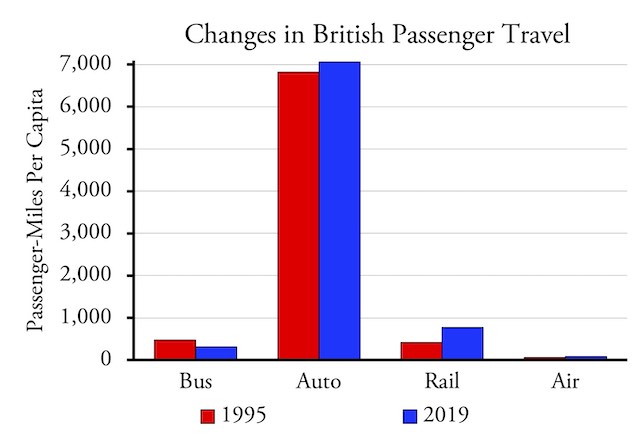

Under the franchise system, rail travel rapidly grew, but as of 2019 Brits were still nine times more likely to travel by auto than by train.

Though rail’s share of passenger travel nearly doubled between 1995 and 2019, it is worth noting that this increase came mainly at the expense of buses, not autos or planes. During that same period, rail passenger-miles grew by 116 percent but bus passenger-miles declined by 25 percent.

2023: The Concessions Model

The real damage to the franchise system was done by the pandemic and its associated lockdowns. Ridership in 2020 fell by 70 percent, forcing franchisees to cut back services. The government responded by paying the franchisees to continue operating. Instead of franchisees earning revenues from ticket sales, all such revenues were kept by the government.

Instead of returning to the franchise system as the nation emerged from the pandemic, the government released a new plan in May 2021. Known as the Williams-Shapps plan, it will effectively make the pandemic emergency changes permanent by replacing the franchise system with a concession system. Starting in 2023, most trains will still be privately operated, but operators will no longer advertise their own brands. Instead, all trains would be operated under the name of Great British Railways, which will collect the revenues and pay the private operators on a cost-plus basis. While not complete nationalization, it is a step backwards from the franchise system.

Under the concessions model, people like Jeremy Corbyn will no longer be able to blame private operators for overcrowding, delayed or cancelled trains, or train wrecks. All decisions regarding fares, timetables, the number of seats on any given train, and maintenance will be made by the government. Private operators will be practically guaranteed a profit at taxpayer expense. This model will reduce if not eliminate the incentives to provide good service.

Nearly all the problems with the franchise system identified in the Williams-Shapps report were the fault of the government. Supposedly, not enough money was being invested in new infrastructure, which was Network Rail’s responsibility.

American tourists love British and European trains, but unless they are sensibly run they may never recover from the pandemic. Photo by David Gubler.

Other problems weren’t really problems at all: the franchisees operated 75 different kinds of trains, which the report said increased maintenance costs. In fact, it allowed for more innovations. “No commercial airline would have that many types of aircraft,” said the report. But, with 25 franchises, that meant only three kinds of trains per franchise, and plenty of airlines have more than three kinds of aircraft. The “simplification” demanded by the report is likely to reduce service to the lowest common denominator.

The bottom line is that there is no reason to think that changing from a franchise to a concession system will lead to any real improvements. Instead, it is likely to reduce innovation, customer service, and accountability. That in turn is likely to end growth in rail ridership, assuming it ever fully recovers from the pandemic.

A Strange Attachment to Monopolies

The consistent theme of all British rail reforms since 1921 has been a faith in monopolies. The Geddes plan of 1921 assumed that competition did more harm than good. The socialist takeover of the railroads in 1947 assumed that a government monopoly would work better than private semi-monopolies. John Major’s mistake in the 1994 privatization was to keep most franchises as monopolies. The concessions system doesn’t fix that.

Winston Churchill has been quoted as saying, “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing after they have tried everything else.” He probably never said that, but maybe Britain can learn from this idea.

When the concessions system fails, and it will, perhaps Britain will finally do the right thing, which is to privatize its rail system by selling or giving both the infrastructure and the operating rights to private companies. To the extent that it can with the available rail systems, it should have at least two operating companies that compete with one another over major routes such as London-Edinburgh and London-Manchester. Even where there aren’t two rail lines to compete with one another, railways will still have to compete against buses, trucks, and autos. Ownership of infrastructure and trains combined with such competition will give the owners incentives to find the most innovative and cost-effective ways to provide services to the public.

The nation also needs to recognize that passenger trains are not necessarily the transportation of the future. They are not that much more energy-efficient than private automobiles, and they are less energy-efficient than buses. Nor are they more cost-efficient than either autos or buses. If parts of the rail system can’t get along without $5 billion in annual subsidies, perhaps those parts don’t need to operate at all.

Randal O’Toole, the Antiplanner, is a transportation and land-use policy analyst and author of Romance of the Rails: Why the Passenger Trains We Love Are Not the Transportation We Need. Masthead photo of the Cross Country train is by David Gubler.

Begun in 1994, it had been completed by 1997. The deregulation of the industry to privatization.. Amtrak was destined to be privatized for 50 years…..

The nation also needs to recognize that passenger trains are not necessarily the transportation of the future ”

With gas prices as they are and UK geography…. rail is significantly more efficient than driving moderate distances…. A paper published by the Ohio State University states that millennials are buying 30% fewer cars than the previous generations. The paper also says that of the respondents who do not own a car, 42% responded it was due to financial reasons, but 58% said it was because they do not need to own one.

Lazy reader wrote, “A paper published by the Ohio State University states that millennials are buying 30% fewer cars than the previous generations. The paper also says that of the respondents who do not own a car, 42% responded it was due to financial reasons, but 58% said it was because they do not need to own one.

A paper published by Ohio University states, “By 2030, driverless cars are likely to become a part of the mainstream, and, by 2050, these cars will become the primary mode of transport in the country.”

While I agree with the basic conclusions of this paper, I should point out that Britain kept on using steam locomotives so long because Britain didn’t have significant local oil supplies at the time, whereas the US did. Having to import oil made the country much more vulnerable in WWII to oil supply than local coal. Britain then started to convert to diesel locomotives and then got hit by the oil shortage of the Suez crisis https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suez_Crisis which causes a new short-term leas of life for steam locomotives. So part of Britain staying with steam locomotives so long was because of energy security.

UK and Japan are unique rail nations. Their geography is north south oriented mostly…

This geographic arrangement makes the nations perfectly suited to carrying large volumes of people by rail. What UK should have done was privitize the infrastructure building, as electrification of rail stock….without diesel costs, they’d have trains running all day regardless of cost. A huge locomotive like this uses an average of 1.5 gallons of diesel per mile (352 L per 100 km) when towing about five passenger cars.

An electric train, In most trains, the power ranges anywhere between 5000 to 7000 horsepower (3.72 Megawatts…

Siemens’ Mireo train platform for regional and commuter rail—boasting weight reductions and improved aerodynamics. Configurations range from two to seven cars, and top speed, depending on the version, ranges from 87 to 124 mph. On batteries.

GE’s new battery powered locomotive, in partnership with BNSF, with a heavy-duty freight-train approach—packing in more than 2,400 kilowatt-hours and potentially going hundreds of miles on battery power.

Potential for battery driven trains, means you don’t to electrify the track….

83mpg, if I’m doing the math right. I used 25 passengers per car.

Shades of AOC crying, looking at an empty parking lot on the Texas-Mexico border. I wonder if Corbin was wearing his famous Get off my lawn! old man black socks with shorts combo?

I’m going to keep looking but so far I’ve found little (apparently) reliable information on energy use (including meaningful numbers) by railroads and others. This is the one bit I’ve found …

“In 2020, CSX moved a ton of freight 508 miles on a single gallon of fuel on average.”

https://www.csx.com/index.cfm/about-us/responsibility/environment-and-efficiency/

FedEx tracks and trumpets it’s gains in fuel efficiency as well as publishing it’s goals and plans for the future … with numbers.

https://www.fedex.com/en-us/sustainability.html

UPS …

https://about.ups.com/content/dam/upsstories/assets/reporting/sustainability-2021/2020_UPS_SASB_Standards_Table_081921.pdf

(I like the three-wheel pedal powered delivery machine on the cover.)

My view is that if they’re not shouting about it with numbers, it ain’t happening.

“American tourists love British trains…”\

I stood up, packed shoulder to shoulder, tummy to tummy, derriére to derriére, from London to Penrith, Newcastle to Peterborough, and Briston to Cardiff. This American tourist says hard pass on any future British railway journeys. (Chapeau to the UK standard of personal hygiene, though!)

You could have taken a bus instead: