Most central Oregon residents are familiar with the Santiam Wagon Road, which parallels U.S. highway 20 up the Cascade Mountains from Sweet Home to Santiam Pass and then down the other side to Sisters. Parts of it are still open as a gravel road that is frequently used by recreationists and the occasional log truck. Other parts have been downgraded to a trail that is less frequently hiked. I’ve both hiked and driven much of the route.

Much of today’s post is based on this book by Cleon Clark, who wrote it after retiring from a career with the Deschutes, Ochoco, and Malheur national forests, all of which were crossed by the wagon road. This book was published by the Deschutes County Historical Society in 1987 and is not copyrighted, so I am making it available for download here. Click image to download the 22.5-MB PDF of this 122-page book with two large maps.

Much of today’s post is based on this book by Cleon Clark, who wrote it after retiring from a career with the Deschutes, Ochoco, and Malheur national forests, all of which were crossed by the wagon road. This book was published by the Deschutes County Historical Society in 1987 and is not copyrighted, so I am making it available for download here. Click image to download the 22.5-MB PDF of this 122-page book with two large maps.

What most residents don’t know is that the Santiam Wagon Road is only part of what was supposed to be a road from Albany, in the Willamette Valley, to the Snake River on the eastern boundary of the state. Even fewer realize that this road was part of one of the biggest land scams in the state, even bigger than the Oregon & California Railroad scandal in the sense that the owners of the Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Wagon Road company got away with their scam, while the O&C Railroad did not.

The Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Wagon Road Company was started as a well-intentioned effort by a group of farmers and ranchers in Linn County (of which Albany is the county seat) to provide people with access to the grasslands and potential farmlands of central Oregon. In the spring of 1866, at a cost of something less than $15,000 (about $300,000 in today’s money), they opened a road from Lebanon up the South Santiam River to Camp Polk, which is currently known as Sisters, and to the Deschutes River. They then charged tolls to use it.

It wasn’t a very good road. Most of the route was heavily forested with gigantic trees that were difficult to cut down and impossible to get to a mill. The road they built was mostly just 6 to 7 feet wide, so narrow that wagons would often rub on the sides of huge trees. Some of the stumps of trees cut for the road were so high they scraped wagon axles. Turnouts for passing on-coming wagons were rare, often as much as a half-mile apart. At places the road was up an 8 percent grade and it sometimes crossed swampy soils. The road also crossed the South Santiam River nine times yet there were no bridges until 1887.

Despite the road’s deficiencies, it proved popular, with hundreds of wagons using it on some summer days. Initially, tolls were $2 to $6 per wagon, depending on the size; 10¢ per head of sheep; 37-1/2¢ per head of cattle; and $1 for a horse and rider. Local residents could buy annual permits for $5 west of the summit and $2.50 east of the summit. (Multiply by 20 to get today’s dollars.) These tolls were reduced over time even as the road was improved with bridges, corduroy over the swampy areas, and wider tracks.

Unfortunately, the good people of Linn County who built the road then got greedy. After Congress gave Michigan and Wisconsin a land grant to build a military road from Copper Harbor to Green Bay, Oregon Senator Benjamin Franklin Harding introduced a bill to give a land grant for a military road from Eugene to the eastern boundary of the state, which was known as the Oregon Central Military Road. Congress passed this bill in 1864 with little debate.

(There was actually some debate over the Michigan-Wisconsin land grant, but the Congressional Globe, which is what the Congressional Record was called in those days, does not say what it was about. It only says that the issues were “all harmonized” by the time the bill was passed On the day the bill was introduced, there was actually far more debate about a proposal to spend federal dollars to sprinkle water on Pennsylvania Avenue when Congress was in session so members of Congress would not have to get dust on their clothes.)

In any case, the Linn County gentlemen didn’t want to be left behind by Eugene. Harding’s bill had passed the last day he was in office, so the owners of the Santiam road went to Senator James Nesmith. With his sponsorship, Congress passed a bill for a wagon road from Albany to the eastern boundary of the state on July 5, 1866.

For what it’s worth, Harding and Nesmith were both Democrats and both were farmers in the Willamette Valley, though neither lived in Linn or Lane counties (of which Eugene is the county seat). However, pork barrel is a bi-partisan issue, for in 1867 it was Republican Senator Henry Corbett who herded a bill through Congress for the Dalles military road, which was supposed to go from that town to the eastern boundary of the state via Canyon City. This again passed without debate, though Congress was still debating how much it should spend sprinkling water on Pennsylvania Avenue to keep the dust down.

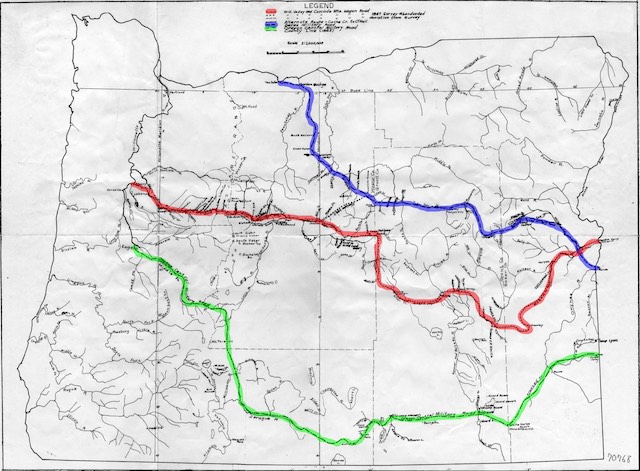

This map shows the supposed location of the Dalles Military Road in blue, the Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Road in red, and the Oregon Central Military Road in green. This map is from the above book but I added the colors. Click image for a larger view.

Once the Albany bill was passed, the owners of the Willamette Valley & Cascade Mountain road did several things to maximize the number of acres they would get. First, the bill specified a road from Albany but their road started in Lebanon, 16 miles away, because someone else had had already built a road between Albany and Lebanon. Not willing to let this opportunity go to waste, they immediately took credit for the road that someone else had built so they could get an additional 30,000 acres of land.

Second, to make it appear that they had built the Santiam Wagon Road in response to the Congressional land grant, they perjured themselves about the dates they had completed the road. It isn’t clear from the law that this mattered, but they lied about it anyway.

Third, and most importantly, they basically faked the construction of a road from the Deschutes River to the Snake River. They built no bridges. They cleared little or no timber. In one place where they said they had graded the road on a hillside, all they did is install a 10-inch-wide trench to hold the upper wheels of a wagon. In some places they did nothing more than drive a wagon over the route. In one 80-mile section, they may not even have done that.

Finally, the route they chose was in places extra circuitous in order to be eligible for more acres of land. Critics of railroad land grants sometimes claimed that the railroads did this, but it would be hard to find any examples. However, a close look at the above map of the WV&CM road shows it doubling back on itself in a place in eastern Oregon known as Crowley.

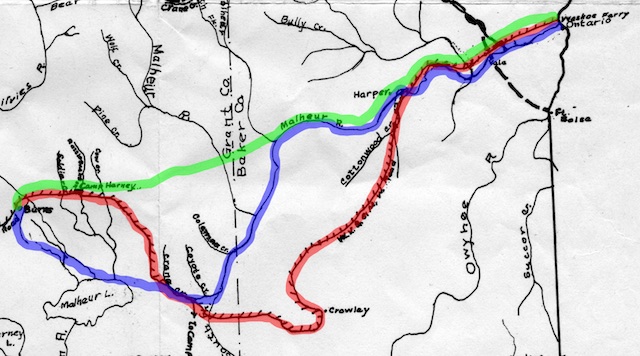

This map shows the supposed route of the WV&CM road from the present city of Burns to the Snake River in red, the later railroad route in blue, and the current highway route in green. The rail route was 6 miles shorter (and would have been 7 miles shorter if it had gone through Camp Harney as the wagon road did) and went up fewer and gentler grades. The highway route went over three ridges, the same as the wagon route route, and saved 32 miles. Most important, the rail line and highway were actually built while most of the WV&CM route was mainly just a line on a map to justify getting thousands of acres of additional land.

This might make sense if the topography required it, but it didn’t. In fact, in 1915 the Union Pacific built a rail line that went straight up the South Fork of the Malheur River. This route was a bit windy but it had a very gentle grade. In contrast, the route chosen for the wagon road unnecessarily goes over three ridges from Crane Creek to Cottonwood Creek, then from Crowley Creek to a different Cottonwood Creek, then from there to Heath Creek before arriving at the South Fork of the Malheur (which it had crossed 70 miles before).

Even with the windiness, the Union Pacific route from Ontario to Burns was at least seven miles shorter than the wagon road route for the same journey. Even shorter is the current highway route, which climbs three different ridges, saving 32 miles over the wagon road. The longer route allowed the wagon road company to get 21 extra square miles or 12,000 acres (vs. the rail route) or 96 square miles or more than 60,000 acres (vs. the highway route) of additional land.