This is a continuation of my posts about the Willamette Valley & Cascade Mountain Wagon Road.

Taking a page from his father’s example of the Minnesota mineral lands, Louis Hill turned his timber lands in Oregon into a trust. Louis, however, wasn’t as generous as his father. Instead of making Great Northern Railway stockholders the beneficiaries of the trust, he created the trust to provide a continuous income for his family. Actually, he made six trusts: one for each of his children, one for his wife, and one for himself. Each had a one-sixth undivided ownership of the timber lands. While the trusts were created in 1917, the lands earned no income for another two decades.

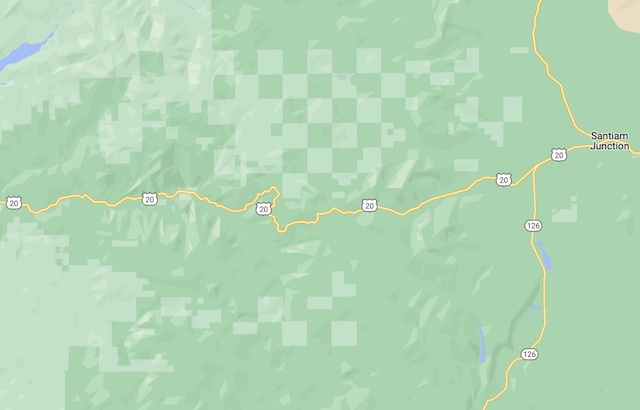

Congress’ policy of granting only every other square mile of land creates a distinctive checkerboard pattern. The dark green on this Google map is the Willamette National Forest while most of the light green squares are Hill trust forest lands. Highway 20 closely follows the route of the Santiam wagon road. Click here to see the same map in satellite view showing clearcuts on the Hill forest lands.

Shortly after Louis Hill acquired those timber lands, a forestry professor at UC Berkeley quit his job to start a forestry consulting firm in Portland. Dave Mason was a prophet of sustained yield forestry, which he described as “limiting the average annual cut to the production capacity” of a forest. This was in contrast to most timber land owners of the time, who generally bought land, cut the timber, and then let the land go for taxes.

Mason wrote in 1927 that sustained yield “is most advantageously applied to a unit of forest area sufficiently large to supply continuously an efficient sized plant operating at or near capacity converting the forest products into salable material.” In other words, sustained yield required a block of timber that was several tens of thousands of acres in size. As it happened, that was about the size of Louis Hill’s timber holdings in Oregon, and soon Mason was courting Hill to be able to manage his forests.

Hill hired Mason in 1937, two decades after creating the trusts. One of the first things they did was sell the lands east of the Cascades to Bend sawmill Brooks-Scanlon.

In 1943, that company built a logging railroad from Bend to Sisters and then to its lands on the south and east sides of Black Butte. The logging railroad only lasted until 1956, after which the company moved the logs by truck. Timber cutting continued until 1994 and most of the lumber produced by the mill was shipped out of Bend by either the Great Northern (whose tracks went south to California) or GN semi-subsidiary SP&S (whose tracks went north to Washington, connecting with the Great Northern in Spokane).

Since 1978, the lands have gone through a series of owners. Brooks-Scanlon was taken over by Diamond International, which was taken over by Cavenham Forest Industries which was taken over by Crown Pacific which sold the lands to Willamette Industries. In 2002, Weyerhaeuser bought Willamette Industries in a hostile takeover. It then sold some of the former grant lands to the Deschutes River Land Trust.

The west side lands remained in the Hill family trusts. By an amazing coincidence, SP&S subsidiary Oregon Electric built a line through Lebanon to Sweet Home that opened in 1932. Any timber cut from the Hill Family Lands would be tributary to Sweet Home and Lebanon. Another branch of the railroad went up the Callapooia River, where it collected logs to take to lumber mills.

Mason arranged to sell timber from the Hill holdings to two companies: Willamette Valley Lumber, which built a mill in Sweet Home, and Santiam Lumber, which built a sawmill in Lebanon. The railway brought logs to the mills and carried lumber from the mills to eastern markets.

“These extensions became a very profitable source of freight traffic for the” Oregon Electric, says the Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society. In 1950 the two lumber companies merged and became Willamette Industries, which later owned the east-side lands. Louis Hill probably didn’t worry about the ethics of developing the land with his own railroads because he had retired as president and chairman of the board of Great Northern and, though he remained on the board, sold most of his stock in the company.

Hill died in 1948 and he and his wife left all of their fortune to a foundation he set up called the Lexington Foundation, later the Louis & Maud Hill Family Foundation and even later the Northwest Area Foundation. The charity made donations to non-profit groups in the states once served by the Great Northern Railway.

The Hill trusts made up most of his legacy to his family. They were so important to the family that his son, Louis Hill Jr., lived in Sweet Home for several years so he could learn the forestry business direct from Dave Mason and his associates at Mason, Bruce & Girard.

Before he died, Louis Hill Sr. appointed a bank called First Trust to act as trustee for the family trusts. The trustee and Mason, Bruce & Girard agreed to have Willamette Industries cut all of the old-growth timber on the land by 1986. After that, timber harvests and revenues dramatically declined because most of the trees growing on the land were too young to be merchantable. One of the forest managers called the following years a “black hole” because revenues would be so low.

In the 1970s and 1980s, private timber managers all claimed to practice sustained yield forestry yet didn’t plan to cut the same amount of timber each year. So long as they were growing timber, even if it wasn’t big enough to cut, they considered what they were doing as sustainable. Economically, depending on your predictions of future timber values and future returns on other investments, it might make sense to rapidly liquidate the timber and put some of the revenues in other assets to live off of until the second-growth timber is mature enough to cut. I have no idea what Dave Mason would have thought of that, but it doesn’t seem to go along with his idea of “limiting the average annual cut to the production capacity.”

If a forest manager or trustee plans to rapidly liquidate someone else’s timber, they should at least tell their client or beneficiary what is going to happen so they can save some of the revenues they are receiving. First Trust apparently didn’t do that, so when it announced to Hill’s children and grandchildren that they weren’t going to earn much money from the forests for awhile, they were shocked.

This is the court decision preventing Maud Hill Scholl from firing the trustee for the Hill lands. Click image to download a 284-KB PDF of the decision, which provides a lot of background about the trust.

This is the court decision preventing Maud Hill Scholl from firing the trustee for the Hill lands. Click image to download a 284-KB PDF of the decision, which provides a lot of background about the trust.

Maud Hill Schroll, Louis Hill’s daughter, immediately tried to fire First Trust and the forest managers who, in her opinion, had mismanaged the land her father left the family. First Trust fought this and the court agreed that she didn’t have the right to do so. Apparently, Louis Hill gave his wife the right to change the trustee but neglected to give any other family members the right to do so after she died.

The trusts will expire in 2026 and family members will then be able to decide what to do with their lands. In the meantime they were forced to scramble for income to continue to live in the lifestyles to which they had been accustomed. Don’t feel too badly for them, though, as they continue to live in fabulous homes like this one in Pebble Beach, California, which is owned by Louis Hill’s grandson, James J. Hill III.