Government subsidies to all modes of transportation except highways greatly increased during the pandemic even as most passenger transportation declined. According to data recently released by the Department of Transportation, subsidies to driving rose 39 percent in 2021 than 2019, while subsidies to all other passenger modes increased by 180 to 350 percent.

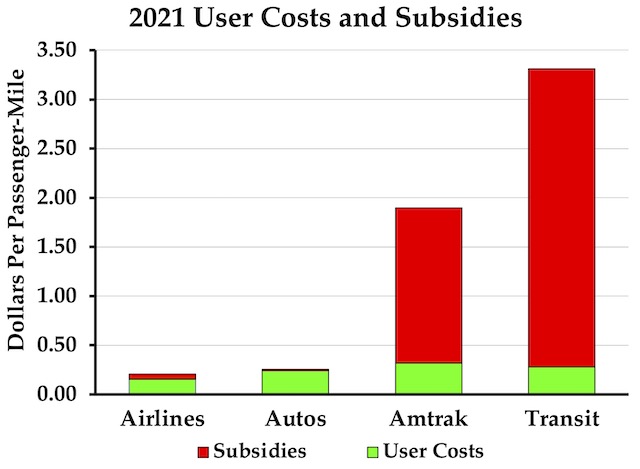

Per passenger-mile subsidies to Amtrak were 30 times greater than subsidies to air travel in 2021, while per passenger-mile subsidies to transit were more than 230 times greater than subsidies to driving.

According to just-released table HF-10 from the 2021 Highway Statistics, government agencies spent $97.5 billion in property taxes and other general funds on highways in 2021, up from $80.3 billion in 2019. However, part of this expense was offset by diversion from highway user fees to transit and other non-highway activities. These diversions amounted to $38.1 billion in 2021, up from $33.3 billion in 2019. The net subsidy to highways, then, was $59.5 billion in 2021, up from $45.1 billion in 2019.

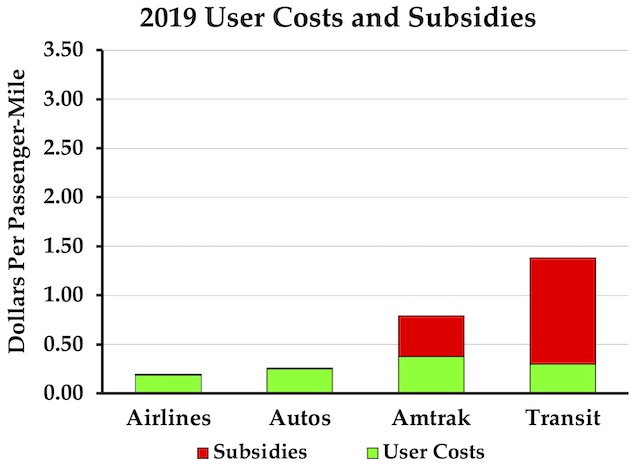

To ease visual comparisons, the vertical axis on this chart is the same as on the 2021 chart.

Highways hosted 4.7 trillion passenger-miles of travel by cars, light trucks, and motorcycles in 2021, down only slightly from 4.9 trillion in 2019. We don’t have 2021 ton-miles of highway freight yet, but 2.5 percent more ton-miles were shipped over the road in 2020 than in 2019. Counting just travel by autos and motorcycles, subsidies rose from 9.2 cents to 12.7 cents per passenger-mile, a 39 percent increase. The subsidy and the increase will be smaller when freight is accounted for.

According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (which I can no longer find on their web site but which has been reprinted by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank), Americans spent $1.13 trillion buying, operating, and insuring their autos in 2021, down from $1.23 trillion in 2019. That works out to 24.2¢ per passenger-mile in 2021, down from 24.9¢ in 2019.

To account for freight’s share of subsidies, I compare total consumer expenditures on driving ($1.23 trillion in 2019) with total expenditures on highway freight (2.368 trillion ton-miles times average shipping rates of 17.84 cents per ton-mile in 2019), which equaled $422 billion in 2019. That represents 24 percent of consumer expenditures on highway travel, so I would attribute 24 percent of the subsidy to freight and 76 percent to passenger travel. That means the 2019 subsidy per passenger-mile was about 0.68¢. Until more information about 2021 highway freight is available, we can’t make the same calculation for that year.

Airline subsidies can be calculated by comparing government revenues from airlines (mainly ticket taxes) with government expenditures (mainly on airports and air traffic control but also in COVID relief funds). Unfortunately, 2021 data aren’t yet available, but 2020 subsidies were 240 percent more than in 2019 while 2021 passenger-miles were 25 percent lower than 2019. If 2021 subsidies prove similar to 2020, then the subsidy per passenger-mile grew from 1.1 to 5.1 cents. Meanwhile, airline fares per passenger-mile averaged 15.6 cents in 2021, down from 18.6 cents in 2019.

Amtrak subsidies can be calculated from the state-owned company’s monthly performance reports. Since September 30 is the end of Amtrak’s fiscal year, the year-to-date data in the reports for September show the results for the year. Each report shows Amtrak’s operating expenses, capital expenses, fare revenues, food & beverage sales, and state subsidies (which Amtrak misleading counts as a revenue, not a subsidy).

The report shows that Amtrak carried 6.5 billion passenger-miles, earned fares and food & beverage revenues of $2.5 billion, and spent $2.7 billion more than those revenues.

The 2021 report shows that Amtrak carried 2.9 billion passenger-miles, down from 6.5 billion in 2019. Fares and food & beverage revenues were $0.9 billion in 2021, down from $2.5 billion in 2019. Total subsidies were $4.5 billion in 2021, up from 2.7 billion in 2019.

Based on this, average fares declined from 37.5¢ per passenger mile in 2019 to 31.8¢ in 2021. Amtrak subsidies rose from 41.2¢ per passenger-mile in 2019 to $1.58 in 2021.

The National Transit Database shows that transit is the most subsidized mode of transportation. Between 2019 and 2021, average fares declined from 29.7¢ to 28.2¢ per passenger-mile, while subsidies rose from $1.08 to $3.03 per passenger-mile. Keep in mind that most of the financial information shown here is based on fiscal years while the highway driving and air travel passenger-miles are based on calendar years. This could distort the results slightly if COVID had a bigger impact on the 2021 fiscal year than the 2021 calendar year.

Some of these subsidies will be lower in 2022 and 2023 as travel has grown since the depths of the pandemic. Given the money that Congress threw at Amtrak and transit in the 2021 infrastructure bill, however, the subsidies to those modes might actually increase still further. Certainly they won’t return to 2019 levels, while subsidies to driving and flying probably will.

The infrastructure bill gave Amtrak $66 billion—$13.2 billion/year over the 5-year life of the bill.

In 2022, Amtrak carried 11.47 million round trips. So, that subsidy alone amounts to $1,151 per round trip!

Further, the annual subsidy is $39 per capita per year from the pockets of 335 million Americans, even though the average American takes a round trip on Amtrak once every 29 years.

All this is attributable to a president who has not the slightest clue about transportation economics.

Henry Porter,

To be fair, you are mixing capital subsidies (which were the $66 billion in the infrastructure bill) with operating subsidies. The benefits of capital subsidies should be spread out over 30 or more years, not just counted against 5 years of revenues. The results still look bad for Amtrak and are less disputable.

Fair enough.

Calculated your way, from the 2021 Amtrak September 2021 report (linked in you article), Amtrak carried 12.167 million passengers 2.8586 billion passenger-miles in 2021, for an average 235 miles per trip. At $1.58 per mile, that’s a subsidy of $371 per trip…$742 per round trip, exclusive of capital subsidies (which are being squandered expanding Amtrak into even less profitable areas).

When an average Amtrak passenger buys a ticket for an average round trip, he or she pays $149 and taxpayers pay $742.

Let me argue against just one point here.

Randal loves passenger mile comparisons because they make modes that serve longer trips look like they’re achieving more, but are they?

Let’s say my 2 mile transit commute costs the agency $2, so if an 8 mile car commute cost a total of $4, Randal would say driving is twice as efficient. In a narrow sense, sure. But that doesn’t mean we can just replace that transit trip with a car trip and have it be cheaper.

First, costs like parking will stay the same on a shorter trip. In fact, urban areas where most of these transit trips are taking place have scarce land, and it is a serious, tangible benefit to not need somewhere to put your car when you get where you’re going. The average efficiency of those 3.5 trillion miles racked up on highways doesn’t scale down to short urban trips where signal, bridge and ramp infrastructure is more complex and multiple times more expensive.

So if we replace those specific transit trips with car trips, we won’t be saving any money. We’ll be jamming more cars into the places where they cost the most to support. If we try suburbanizing transit-friendly cities to fit more cars, we’ll just increase trip lengths and won’t be saving anyone money either.

The O’Toole philosophy is basically “Move the store from 1 mile away to 20, and as long as transportation costs increase less than 1900%, you’ve made the trips more efficient.” Even if he doesn’t say it explicitly, that’s the end he’s arguing for. Well guess what, our country tried it, and we have higher transport CO2 emissions per capita than any other country. But hey, at least you got to drive further.

Alex C Davis,

Thank you for your comments. My argument is that, if I have a 10-mile radius of destinations that I can easily reach, I can reach more jobs, more stores, more parks, more schools, and more of everything else than I could reach if I only have a 2-mile radius. Having more options means a more highly productive work force (because people are more likely to find jobs that best suit them), lower-cost consumer goods (because retailers will work harder to reduce prices if they face a lot of competition), and better of everything else as well.

I’m not the only one who thinks so. Something like 97 percent of American workers either live in a household with a car or drive alone to work even though they don’t have a car in their household. People aren’t choosing to drive because they were force to do so by some dark conspiracy. They choose to drive because driving is the most economical way for them to access all sorts of economic and social opportunities. Europeans drive a lot too, far more than they use transit or ride trains, so Americans aren’t unique in this regard.

The problem with your 10 mile “Radius of Wonder” is that it requires 25 times the utility infrastructure of Alex’s 2 mile radius Walkable Community. Your arguments leave out a key fact of Suburbia, that it’s utility and road infrastructure is unsustainable. The ideal society you argue for is pointed out by others to be an unsustainable Ponzi Scheme. And they are just using is math to prove their point. I did a reasonable effort at searching your blog, and found no discussions on the financial sustainability of suburbs. So I’d like to see your rebuttal to arguments such as this. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Nw6qyyrTeI

Thank you for your response! My rebuttal would be that my two mile radius is just as good as your 10 mile radius if I can fit five times as much stuff in it. This is a very old debate, between speed of transportation and proximity of destinations. I think that dense development is a more effective way of achieving economy of scale and giving people more freedom, than trying to put them all in cars.

First, energy efficiency. It’s more energy efficient to travel shorter distances. This is true for both transit and cars. And as I’ve seen you bring up in presentations, Europeans who drive still drive significantly shorter distances. You’ve argued this is a sign of less freedom, but in terms of climate and cost efficiency, it’s a much better deal.

There’s also infrastructure. If buildings are on average half as far apart, you need half the pipes, wires and pavement to support them.

I’m using the word “radius” kind of loosely here. For transit, the travel time radius is usually less circular than for driving. But that’s only a problem in a diffuse land use pattern.

I know you often bring up space intensive land uses like warehouses as an example of jobs you need a car to access, but are they? Just look at the difference between the warehouse district in Secaucus, NJ and the warehouse district in Cranbury, NJ. The Secaucus district has convenient bus access to the surrounding urban centers, broadening the labor base. And because it’s more space efficient, it can be closer to more people and get more products delivered faster.

So yeah, in a suburban country, more people will drive to access sprawling amenities. But towns and cities can deliver that same economy of scale for less energy and infrastructure using transit and transit-friendly development.

Something else I wanted to mention. I’m an urban planning student at Rutgers currently working for NJ Transit, so you’ll definitely find me in the urbanist crowd. But I do often recommend friends read some of your blog posts. Your ideas have definitely challenged a lot of urbanists to think more clearly about their goals.

Alex, your 2 mile walkable community is equivalent to the 10 mile (and more) car required radius. And the cost of infrastructure for your community is exponentially smaller. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Nw6qyyrTeI