Spending billions of dollars on on transit infrastructure, as proposed by a group called the Transit Alliance for Middle Tennessee, would be a complete waste. The group was formed to support the city’s 26-mile, $5-billion light-rail proposal that was rejected by voters five years ago. Now that the pandemic has proven that Nashville doesn’t need any transit infrastructure, the group is reemerging as an “advocate for action.”

The group wants “multimodal transportation,” which to them means bus-rapid transit on dedicated lanes, light rail, commuter rail, and maybe even heavy rail and monorail. For some reason, the group doesn’t mention cars, trucks, bicycles, pedestrians, scooters, and local buses, all of which make Nashville’s existing transportation infrastructure pretty multimodal.

In a press conference on Monday, the group decried the fact that Nashville is the second-most auto liberated (they used the term auto-dependent) city in the nation. According to the 2021 American Community Survey, 95.0 percent of households in the Nashville-Davidson urban area had at least one automobile in 2021, and the number of households with an automobile grew by 8.7 percent between 2019 and 2021.

In 2021, only 0.9 percent of workers in the region took transit to work, down from 1.6 percent in 2019. The number of people working at home increased by 172 percent, which caused the number driving alone to work to decline by 15 percent while the number taking transit to work fell by 39 percent.

In addition to buses, Nashville has the Music City Star, a so-called commuter train that goes nowhere. In 2021, the American Community Survey reported that about 5,300 Nashville-area workers said they took the bus to work, but only 145 took the train. That may be high, as the 2021 National Transit Database reported that the train carried only 137 riders per weekday (though some of the difference is due to the database being based on fiscal years, which in Nashville’s case ends on June 30).

The Star was supposed to carry 1,400 riders per weekday in its first year, but instead carried less than 600. By 2019, after more than a decade of service, Star weekday ridership was still only 1,115. Despite the Star‘s failure, the Transit Alliance of Middle Tennessee wants to see more — and more expensive — trains like it built in the region.

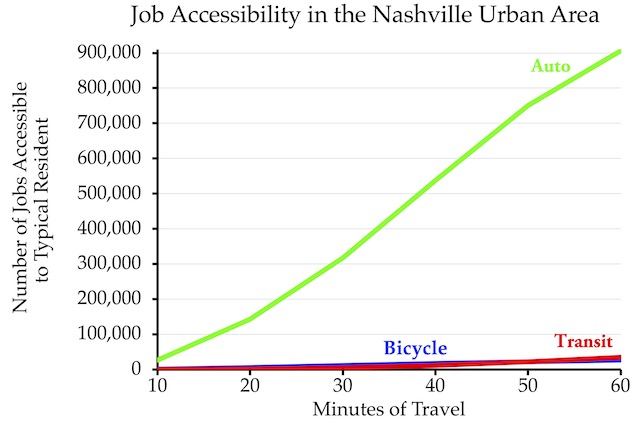

Source: University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory data for 2019.

One of the speakers at the press conference said she wanted transportation to give people more economic opportunities. The best way to do that is to make sure they have access to a car. As shown in the chart above, a 10-minute auto drive allows the typical Nashville resident to reach more jobs than a 50-minute transit ride, and a 20-minute auto drive accesses four times as many jobs as a 60-minute transit ride. Bicycles can reach more jobs than transit in trips of 50 minutes or less. Spending more money on transit won’t fix that, as even in New York City transit can’t access as many jobs as autos or bicycles.

The 2021 American Community Survey counted the number of households that have more workers than vehicles. Based on this table, the region has about 36,000 workers who don’t have their own vehicles. Dividing the $5 billion the alliance wanted to spend on one light-rail line by those 36,000 workers results in more than $135,000 per worker, which would buy each of them a new car every ten years for the expected lifespan of a light-rail line.

It is likely that many of those workers don’t need cars anyway. Of the 13,800 Nashville-area workers who lived in households without cars in 2021, a third drove alone to work (probably in employer-supplied vehicles) and 19 percent carpooled. Less than 16 percent took transit to work.

Although it wasn’t mentioned in press reports, no doubt someone at the transit alliance event claimed that transit saves energy and reduces greenhouse gases. That needs to be added to Wikipedia’s list of urban legends, as it’s far from true in Nashville’s case. In 2019, Nashville transit used more than twice as much energy and emitted far more greenhouse gases per passenger-mile than the average light truck, not to mention the average car. Of course, in 2021 it was even worse.

Nashville transit is recovering from the pandemic more than most, as it carried about 82 percent as many riders in February 2023 as it did in February 2019. In the five years before the pandemic, however, ridership was slowly declining. The big danger with rail transit projects, seen in Los Angeles, Phoenix, Portland, San Jose, and many other cities, is that cost overruns force agencies to cut back on bus service, accelerating ridership declines. Nashville’s transit system is best off not having a light-rail money pit.

In short, the Transit Alliance of Middle Tennessee is a small group of people who want to spend billions of dollars of other peoples’ money on projects that will do nothing for 99 percent of the residents of the Nashville region. Nashville taxpayers have to hope that most of the region’s politicians are willing to say “no” to transit boondoggles.

For those living the region, note there is a bad chance that your city and county is giving taxpayer money to Transit Alliance for Middle Tennessee. They ain’t limited to Nashville and Davidson. Don’t be shy about encouraging your local officials to stop funding the madness.