Taxpayers are spending more to subsidize low-income housing and yet getting less. Since 1987, the biggest source of funds for affordable housing has been low-income housing tax credits, which offer billions of dollars in reduced taxes if they dedicate some of the housing they build to households earning less than 60 percent of the median incomes in their regions. These tax credits are given to state housing agencies based on each state’s population and the housing agencies grant them to developers through a competitive application process.

Source: LIHTC Database, Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://lihtc.huduser.gov.

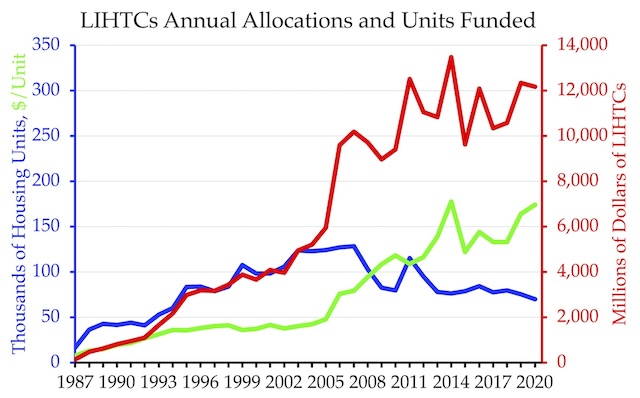

As the above chart shows, the numbers of housing units built with such funds roughly kept pace with the annual subsidies until 2004. Then subsidies dramatically increased while the number of housing units built declined. Between the 2000s and 2010s, the average inflation-adjusted subsidy per housing unit grew by 125 percent. Since 1987, 30 states have created their own affordable housing tax credit programs as well as other housing subsidies, so when they are all added together it is likely that the subsidies per housing unit have grown even faster than shown in the chart.

Economists have questioned the tax credit program for several reasons. A 2009 study found that homes built with tax credits cost 20 percent more per square foot than comparable unsubsidized homes. Another study found that virtually all developers sell their tax credits to banks for at least a 25 percent discount, so $1 billion in tax credits produces less than $750 million in new housing. Other studies have concluded that most of the program’s benefits are captured by developers, not low-income tenants and that construction of subsidized housing crowds out new unsubsidized homes such that it takes five subsidized units to get a net of one new home in an area.

The economists who did these studies generally agreed that rent-voucher programs were more effective at helping people than building housing projects. Despite this, the Biden administration has proposed to greatly increase tax credits in 2024.

A 2017 report on All Things Considered noted the rising costs and declining number of homes built and blamed the trend on the general increase in construction costs. However, home construction cost indices indicate about a 20 percent increase between the 2000s and 2010s, yet subsidized housing costs more than doubled.

Instead, what I suspect has happened is that urban planners have persuaded many of the state agencies that distribute tax credits to focus their funding on New Urbanist mid-rise and high-rise developments. Developers are more likely to receive tax credits and other funding if they build transit-oriented developments even though such developments cost at least twice as much, per square foot, as low-rise construction. Developers don’t care about the rising costs because they get to keep fees that are roughly proportional to project costs, not the number of units they build.

I used HUD’s low-income housing tax credit database to look at hundreds of projects built in Denver, Portland, and Seattle. The database does not specify the number of floors in each project, so I entered the addresses of each project into Google maps and counted the floors using Google streetview.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, almost all projects, except a few in the downtown areas, were two or three stories tall, while the downtown projects were mostly four stories tall. Starting in the mid-1990s, an increasing number of downtown projects were high-rises and projects away from downtowns were mid-rises. By the mid-2000s, construction of two-story projects had practically ended in the cities, but some were still built in the suburbs. By the mid-2010s, many suburb, such as Beaverton and Gresham, Oregon; Bellevue and Issaquah, Washington; and Thornton and Westminster Colorado were also building mainly mid-rise projects.

This trend is also visible in a major change to three-story projects. In the early years, the typical three-story project consisted of buildings surrounded by parking lots whose apartments were accessed by low-cost outside staircases. In later years, most three-story projects fronted on sidewalk and had inside staircases and hallways. Such hallways are as expensive to build as living areas yet contribute nothing to living space. This change clearly shows the influence of New Urbanists, whose standards call for buildings that front on sidewalks and a deemphasis on parking.

Mid-rise construction costs about twice as much per square foot as low-rise, and high-rise is even more expensive, so this shift resulted in higher costs but fewer new housing units. This has harmed taxpayers by increase costs and harmed low-income people by reducing the number of subsidized units available all in the name of an anti-automobile ideology that is questionable in many ways.

I’m pretty sure the trends I found in Denver, Portland, and Seattle are also happening in California and other states that have passed growth-management laws. Since the entire database lists nearly 52,000 different projects, I probably won’t have time to review them all. But if anyone is interested in looking at projects in their region, I’d be glad to help and will be interested in the results.

“But if anyone is interested in looking at projects in their region … ”

Physically driving to and looking at or doing on-line or other research? In either case I’d be interested.

”

This trend is also visible in a major change to three-story projects. In the early years, the typical three-story project consisted of buildings surrounded by parking lots whose apartments were accessed by low-cost outside staircases. In later years, most three-story projects fronted on sidewalk and had inside staircases and hallways. Such hallways are as expensive to build as living areas yet contribute nothing to living space. This change clearly shows the influence of New Urbanists, who calls for buildings that front on sidewalks and a deemphasis on parking.

” ~anti-planner

That’s the issue indoor malls have. They have a ton of indoor common space that needs to be maintained. The rise of these lifestyle centers is because they all but eliminate and lower the costs.

rovingbroker,

I just mean on-line research. Basically, copying addresses in the LIHTC database and entering them into Google maps, clicking on street view, and counting and recording the number of stories. In a few cases, the buildings aren’t visible from street view and then an on-site visit could be helpful. I just skipped those so I didn’t get a 100% sample.

Other than Habitat for humanity, the welfare state has virtually obliterated Mutual aid Groups. The old days they built housing, orphanages, and hospitals.

The US military is one of the largest land owners with 27 Million acres. Just 1% could build 3 story apartments for 1.6 million people.