Who said the following? “The basic objective of our Nation’s transportation system must be to assure the availability of the fast, safe, and economical transportation services needed in a growing and changing economy. . . . This basic objective can and must be achieved primarily by continued reliance on unsubsidized privately owned facilities, operating under the incentives of private profit and the checks of competition to the maximum extent practicable. . . . This means . . . equality of opportunity for all forms of transportation and their users and undue preference to none. It means greater reliance on the forces of competition and less reliance on the restraints of regulation. And it means that, to the extent possible, the users of transportation services should bear the full costs of the services they use, whether those services are provided privately or publicly.”

Click image to go to Bookfinder.com to find the lowest current price for this book.

Click image to go to Bookfinder.com to find the lowest current price for this book.

- Ronald Reagan;

- Milton Friedman;

- Ayn Rand; or

- The Antiplanner?

In fact, the answer is 5. John F. Kennedy. Or at least this statement was contained in Kennedy’s April 2, 1962 message to Congress on having an “efficient transportation system.” This means it was probably written by staffers in the Department of Commerce, as the Department of Transportation did not yet exist. Whoever wrote it was at least willing to talk the talk of free markets and fiscal conservatism.

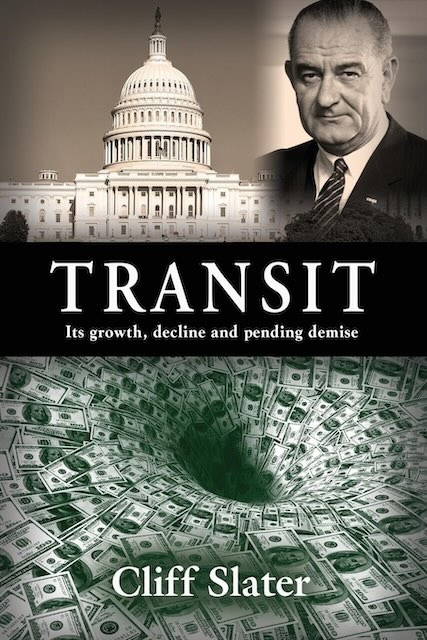

I was alerted to this quote when I read page 147 of Cliff Slater’s new (released December 15, 2023) book on urban transit. I’ve known Slater for many years and when I learned he was writing a book on transit at about the same time my book, Romance of the Rails, was being released, I worried that the two would duplicate one another. Instead, it appears that the two complement one another, as the history he tells is quite different from mine, not because of any disagreements between us but because there is so much history that neither of us could cover it all in a single book.

An example is part IV (pp. 135-214), his detailed story of the passage of the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964. Even as some nameless bureaucrat was drafting the above words, Slater shows that political forces consisting of big-city mayors, downtown property owners, private railroads interested in staunching their losses from running commuter trains, and government-owned transit agencies were working to undermine it.

At the time, there were about 1,100 private bus companies providing transit services in cities and towns all over the country (p. 148). In 1963, the transit industry as a whole lost about $4 million, but a handful of government-owned rail transit agencies in New York, Boston, San Francisco, and a few other cities collectively lost at least $41 million (pp. 166-167). That means the 1,100 private bus companies must have collectively made at least $37 million in profits (about $450 million in today’s dollars). In fact, their profits were even greater as Slater wasn’t able to document the losses from rail transit systems in El Paso, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.

Despite this, proposals to “save transit” in the early 1960s completely ignored the interests of these bus companies. At a meeting of mayors, city officials, and rail transit agencies, the American Transit Association (forerunner of today’s American Public Transportation Association) agreed with the others that any federal funds for transit should not go to private transit operators (p. 147). Their reasoning was simple: most private bus companies were not members of ATA, and since it assessed its membership fees based on the size of the company or agency, it received most of its revenues from the money-losing rail transit agencies, not the few profitable private companies that had bothered to join (many of which quit when it learned that ATA was supporting legislation that would favor public agencies over them — p. 148).

One of the great things about Slater’s book is that his associated web site has all of his footnotes with links to the original sources whenever possible. I downloaded the Congressional Record from which the president’s statement quote above was taken and found that even that statement proposed to discriminate against private operators, indicating the authors talked the free-enterprise talk but didn’t walk the free-enterprise walk.

The statement observed that urban transportation patterns had changed with both people and jobs moving to the suburbs. It further admitted that urban transit agencies had failed to adjust to this change and “remained geared to the older patterns.” It didn’t mention that the private bus companies were adjusting, as many were serving suburban areas, but it was the rail transit agencies that remained stuck with their downtown-centric systems.

The president’s statement then predicted that urban areas would grow to the point that “well over half” of all Americans would soon be living in just 40 urban areas, a prediction that never came close to happening. The statement then leaps to the conclusion that “Our national welfare therefore requires the provision of . . . modern mass transportation to help shape as well as serve urban growth.” To provide such mass transportation, the president proposed that Congress spend $500 million (well over $12 billion in today’s money) over three years on transit capital improvements. None of the money should go for operating funds, the statement said, and none should go to private transit companies.

In short, the reasoning was: 1) We need efficient transportation; 2) Urban transit isn’t working; 3) Let’s throw money at it. There seems to have been a major disconnect in this logic.

Slater shows that the public transit lobby skillfully managed the political system in its favor, effectively screwing both taxpayers and the private bus operators. The arguments it used were the same as the ones we hear today: downtown recovery is essential to urban vitality (p. 152); one rail transit line can move as many people as a 20-lane freeway (p. 151); transit will relieve congestion by getting people out of their cars (p. 157); and so on, all of which are refuted by Slater, often using quotes from people at that time. Such skeptics of socialized transit agencies were able to counter those claims effectively enough in 1964 that the Urban Mass Transportation Act passed Congress by only narrow majorities: 212-189 in the House, 52-41 in the Senate (p. 181).

Once federal money for public transit agencies was unleashed, states and cities across the country quickly took over private bus companies and opposition to federal transit spending evaporated. Later transit bills passed overwhelmingly in both the House by 327-16 and the Senate by 84-4 (p. 188). Now it’s considered apostasy in the transit industry to worry about profits or to ask users pay to the full cost of the services they use.

I regularly rode private transit buses in the 1960s and remember that the private bus companies may have been profitable but their bus fleets were getting old and state public utilities commissions refused to allow them to raise fares to cover the cost of buying new buses. Things might have turned out differently if some of the federal capital funds could have gone to private bus companies to update their bus fleets with the latest buses. Since buses carried two-thirds of transit riders, an allocation of funds based on ridership would have motivate both private companies and public agencies to design their systems to boost ridership, not please politicians.

Instead, we now are spending tens of billions of dollars a year supporting a socialized transit industry that fully expects that the fewer passengers they carry, the more money they will get. Even if you have already read Romance of the Rails, I heartily recommend Slater’s book to get the full story of how we got here.

Urban mass transit act started off as an Equity scam, that turned into welfare fraud.

Emphasis was to bailout the last remaining rail transit systems in just 4 major US cities to great expense. Other cities/states refused accept why they should pay to refurbish, they went on the bandwagon to build rail transit systems of their own they too could enjoy the cronyism.

Pending subsidies to highway construction and YES there were some doozies, including demolition of black/brown neighborhoods without just compensation. Building massive elevated freeways which permanently separated City neighborhoods.

In any case, had such subsidies not come to light, it’d have little effect on driving’s growth. Japan didn’t do what we did. OH WAIT THEY DID on local levels; mass trains did little to stop the 20 fold increase in Auto ownership and passenger driving from 1965-2020.

Anti-planner has his own rules, here’s an official one.

Behind every good walkable “Main street” is adquate parking.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/GG-8OvjXAAAs1KE?format=jpg&name=large

The real solution to transit if it’s to resurge, is deregulation.

Jitney’s were common in San Francisco up til the 70’s. In the 1910s, there were 1,400 jitneys operating in the city, according to SFMTA records, and they remained ubiquitous into the 1970s, patronized by the city’s Asian and Latin community. But around that time the city wanted to encourage public transit use on MUNI and BART. It disliked the competition, so began issuing fewer permits and forcing jitneys to raise fares, as not to undercut the public option. In 1978, the city stopped issuing permits altogether and Jitney’s were sunk. When Chariot started in 2010s following a wave of deregulation they swiftly took market share and by 2015 carrying 50,000 daily riders and by 2017, the company folded because SF reinstated new regulation. At it’s peak Ford owned CHariot operated 100, 14-passenger vans and was carrying 7000 daily passengers; on a 9-5 work day averages 8 people per van per hour. WAY more efficient average occupancy of cars of 1.67

Would you rather have 1000 Jitney’s could carry 70,000 or a quarter of BART’s capacity. But that’s better and less traffic than 41,000 cars. In Chariots case, it’s 100 van fleet ran 7000 (divided 1.67 average) took 4,000 vehicles off the road.

16% San Franciscans are freuqent cyclists, estimates the city has 128,000 cycling trips, in a city of 800,000, no small thing.

Point is, Private transportation is more efficient

Why couldn’t the private Las Vegas Monorail go to the airport, downtown and west wing?

How do you know if “couldn’t?” Maybe it could, technically speaking but because it was private, they chose not to do so for reasons related to profitability, keeping undesirables of their monorail, or “none of your business.”

It’s called FME (Free Market Enterprise) and we need to further restore it.

New planned areas post 1930s is very costly and fiscally difficult to maintain. I wonder why O’Toole hardly ever covers arterial/collector routes also known as “stroads.”

They are highly inefficient and costly. In fact, many sprawl critics like me have more concerns with that type of route than freeways/highways and calm moving streets.

The good news is that roundabouts are mitigating the effects of arterials/collectors. Many new outer ring Houston metro developments have placed them. So now the route is four lanes coming into an intersection as opposed to 7-9.

Stroads are bad. Even the Federal Highway Administration knows it. So now what? Now we look at our local stroads and decide: Should this be a street, or should it be a road? To Auto drivers, it’s a death race. Non-freeway arterial roads, stroads, which typically carry large volumes of traffic at high speeds, are the most dangerous for people on foot, accounting for 60% of all fatalities in US. But as the Antiplanner aruged 6. in his Mobility principles. Segregation of use.

The solution is turn Stroads Into boulevards

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcRfHVwb5aHoaJeIcYp5uqcA9PLmoFl0nj13pReuWtS3dg&s

With fast traffic in center segregated by BARRIERS and Slow controlled traffic in exterior

Well O’Toole hardly talks about that.

He just paints all of the Sprawl critics as tyrants with growth boundaries and wasteful transit projects as their top priorities.

Not only are they tyrants, they are corrupt, lying self-serving, congestion-causing, left-agenda pushing tyrants, as we know here in Pinellas County Florida.

People are angry here after a crime and congestion-causing BRT was put in *against* the wishes of the people, and against formal resolutions passed unanimously by city commissions in two of the three cities it travels through. All to serve monied densification interests.

If that isn’t tyranny, I don’t now what is.

It may be tyranny with a happy face on it, but it’s still tyranny, so “off with their heads” but I’ll settle for confiscation of half of their net worth.

Writers keep ignoring the fundamental fact underlying all mass transit discussion. Density makes a few people rich at the expense of everyone else. This fact was proven in the 1915 Los Angeles of Traffic, which was in fact a brilliant land use treatise.

https://bit.ly/3MqJYM3 1915 Study of Street Traffic Condition in the City of Los Angeles

After WW II, Los Angeles violated every mathematical, topographical and financial rule to create a dense DTLA, e.g. Bunker Hill, and relegate workers to far flung Valleys. That justified freeways but with high density cores meant that no means of transportation could get the worker to the core areas in a reasonable amount of time. Had there been no Bunker Hill etc. and all office space expanded outward with the suburbs, then buses would have done the job since offices would be located near where people lived.

But there were billions of dollars to be made from rapid mass transit. Although Angelenos voted down all project, the Feds finally intervened and gav LA enough money to construct what Angelenos did not want. We liked being 72 suburbs searching for a downtown except one was searching for a downtown as their time had passed. To this day, the corrupt city councils and the corrupt developers continue with the densification and more multi billion dollar subways, as more and more people leave LA as it is too crowed. Also, people HATE mass transit — it is slow, time consuming, expensive, dirty and dangerous. The entire densification- mass transit fraud is transferring hundreds of billions of dollars to Wall Street, while destroying LA as a decent place to live. It is all based on the fact that density increases land prices and the higher the land costs, the more square footage developers pack on to the plots and the higher the mortgages.

Right now Angelenos see without understanding. There are the three high Graffiti Towers in DTLA sitting unfinished since 2019. Why? Because no one will fund them as they are financial lunacy. Since the developer is China, the Feds will not bail out the project until China is completely removed from getting one cent from the project. Then the Feds will give hundreds of billions for the project which will sit mostly empty and the American developer will not have to repay any of the Fed loans. It takes a long time, but over densification kills a city.

What is your solution to the congestion?

You heard of personal rapid transit?

Those towers in LA were built corrupt Chinese developers. Burrowed heavy interest to develop high density luxury towers but had to comply American safety, work standards which became uneconomical.

It’s horrendous aspect Chinese building practices for shoddy, quickly built projects while developers and contractors skim cash with substandard or even fake materials.

It’s got a name TOFU DREG.

And YouTube videos are ubiquitous of these often newly Built projects failing. Condos, apartments, bridges both Highway and Rail. Which begs the question “DID THEY Build their nuclear plants this way” for sake of everyone in Asia I hope not. perfect place to shoot a super hero movies. They can literally break through walls with their fists, no special effects needed.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=s-2DtL-Wjkc