Japan’s population is roughly equal to the five most-populous states of the U.S. — California, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas — concentrated in a nation that has approximately the land area of Montana, which is only about a fourth as large as those five most-populous states. Moreover, well over 40 percent of Japanese live in the Tokyo-Osaka corridor, which is considerably smaller than the Boston-Washington corridor yet has a greater population.

Single-family homes in Japan.

Despite this concentration, most Japanese live in single-family homes. While that percentage has been declining, in recent years that decline has been due to the rise in people living alone. In major urban areas, single-family homes are often on small lots, but they are on large lots in smaller towns and rural areas. Just as in the U.S., most Japanese families aspire to live in a single-family home.

As it happens, while I was in Japan (or just before I left), several reports, articles, and commentaries appeared on the American housing crisis and related issues that are worth addressing here. These include (in chronological order):

- A September 2 article on “how to fix the housing crisis” by Harvard economist Edward Glaeser;

- A September 12 paper on why people think that increasing housing supply won’t make housing more affordable

- A September 15 article asking whether selling federal land could relieve housing prices;

- A September 17 review of a new book on “the hidden story of America’s housing crisis”;

- A September 18 op-ed by Senator Linda Smith and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez arguing that social housing can relieve the housing crisis; and

- A September 20 report discussing the relationship between housing and the stagnation of Britain’s economy.

The most ludicrous of these ideas is the Smith-AOC proposal to reducing housing prices by building government housing. Social housing is aimed at sheltering low- or zero-income people who simply can’t afford housing in any market. It is not a remedy for high housing prices because increased government housing reduces private home construction. One study found that, for every five government-subsidized homes built, four fewer private homes are built. This means that massive amounts of government housing would need to be built to relieve home prices.

Smith and AOC have proposed a bill that they believe will lead to the construction of 1.25 million new homes. But if the five-to-four ratio is correct, this would mean that 1.0 million fewer private homes would be built. The net addition of a quarter million homes to the nation’s housing market of about 130 million homes would have almost no influence on prices.

The other problem with government housing is that it tends to be both expensive to build and of poor quality and undesirable form (i.e., multifamily rather than single-family). The United States is currently building about 1.5 million new homes per year. If we think we need to use government subsidies to increase this to 2 million to relieve housing prices, the government is going to have to build nearly all of those homes itself. Considering how inefficient government is, that would cost around half a trillion dollars per year. Why spend that much when it would be far more efficient to simply let the market build homes that people want rather than have the government build more housing that people don’t want?

Selling federal land will rarely be the solution to high housing prices, mainly because most federal land is not located where housing is a problem. As the article notes (quoting a RedFin economist), “There probably aren’t that many [federal] land parcels that are simultaneously not that valuable to the federal government and very valuable for housing.” However, there is one major exception: Nevada, where the federal government owns nearly 85 percent of land and such land forms a sort of urban-growth boundary around Las Vegas and other urban areas.

The real solution to high housing prices is to open up private lands near urban areas to development. Such private lands have been placed off limits to development by growth-management plans (though they would more accurately be called growth-mismanagement plans) in the more expensive states.

Yet this solution is ignored by Glaeser’s article and the book reviewed on September 17. Both assume that NIMBYism within existing urban areas is the cause of high housing prices when such NIMBYism has zero effect on prices when developers have access to plenty of rural lands for new housing. Glaeser proposes that the federal government impose some sort of housing targets on cities whose median home prices are above $500,000, which is a typical example of imposing central planning on a problem that would better be solved by the market.

Discussions of NIMBYs and YIMBYs invariably mean the substitution of multifamily housing for single-family homes. Yet, as I’ve previously noted here, these are in fact two completely different markets. Some 80 percent of Americans want to live in single-family homes and regard multifamily housing as either temporary housing while they are trying to buy a single-family home or housing for people in certain stages of their lives such as college students or the very elderly.

Glaeser himself grew up in a Manhattan high rise and thinks everyone else should be delighted to live that way. Yet they aren’t, as revealed by a 2018 Gallup poll that found that 40 percent of people living in dense cities wanted to move to lower-density suburbs, smaller towns, or rural areas. The population shifts during and after the pandemic are an expression of this desire. Glaeser himself raised his family in a single-family home on a 6.5-acre lot in rural Massachusetts, a stunning example of what economists call “revealed preference” and what I call “density for thee but not for me.”

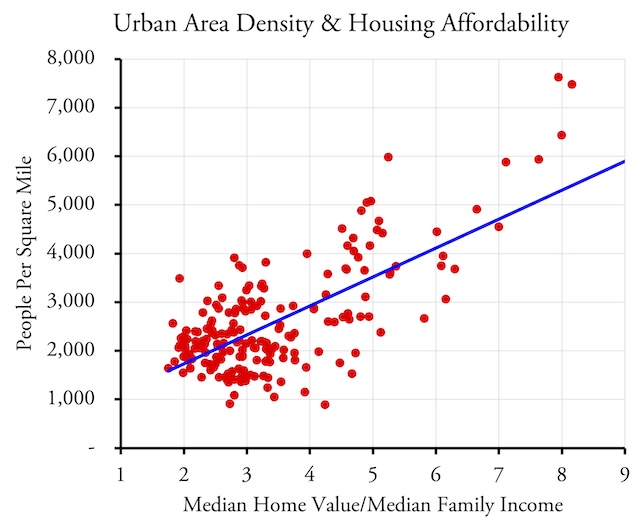

Similarly, the authors of the paper about whether increasing housing supply will make housing more affordable take it for granted that this is true. Yet it is fundamentally wrong to equate multifamily housing with single-family housing. Not only is multifamily housing considered less desirable by most Americans, when it is in the form of mid-rise or high-rise development it costs much more to build than single-family homes. We won’t make housing more affordable by demolishing the kind of housing people want in order to build more-expensive homes that people don’t want. The evidence is plain from census data: the nation’s densest urban areas are also its least affordable.

2020 census data for the nation’s 200 largest urban areas show a clear correlation between increased density and reduced affordability. The causal relationship is also straightforward: people aren’t going to move to a place, making it denser, because they like the fact it is less affordable, but increasing densities will make it less affordable by inflating land prices and increasing construction costs.

The paper that is closest to getting it right isn’t about the United States at all but about the United Kingdom, which has been struggling with high housing prices even longer than the U.S. The paper correctly identifies “the source of the problem” as the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which (with follow-up legislation) put more than 90 percent of the country off-limits to new development. Private home construction collapsed after the law was passed and in every year since then it was lower than every year between 1860 to 1915, when the country’s population was much lower. Between 1950 and 1980, the government tried to supplement low levels of private construction with more social housing, but this housing was undesirable and often poorly built. Since 1980, the government hasn’t even tried to keep up with housing needs, with the result that Britain has some of the least affordable housing in the world.

In contrast with Britain, the United States saw a huge increase in home construction following World War II as builders such as Henry Kaiser and William Levitt bought rural land near major urban areas, subdivided it, installed basic infrastructure, and built millions of homes that they sold for quite affordable prices. As a result, by 1970 homeownership rates were high among both the middle class and the working class and U.S. wealth inequality was probably at its lowest ever, or at least since 1900.

Increasing homeownership and declining inequality trends were halted in states that passed growth-management laws, including Hawaii (1961), California (1963), Oregon (1973), and Washington (1990). Such laws were often directly or indirectly inspired by the Town and Country Planning Act and have had the same results: housing prices have gone up, homeownership rates have declined, and wealth inequality has increased.

There is plenty of room for new housing if states, counties, and metro governments would lift their rural land-use restrictions. Data from the 2020 census show that nearly 70 percent of the four counties surrounding San Francisco (Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, and San Mateo) is rural. More than three-fourths of Santa Clara County (San Jose) is rural. Most of these rural lands are private and many of the landowners would be happy to develop them or sell them to housing developers if only the counties would let them.

The data show that 98.9 percent of Oregon remains rural, yet advocates of these policies freak out when the governor of Oregon proposes to add a mere 373 acres to Portland’s urban-growth boundary to make room for a chip factory. Even the governor hasn’t dared propose to abolish growth boundaries to make room for new housing.

A full 95.0 percent of California, 98.5 percent of Colorado, 95.3 percent of Hawaii, and 96.5 percent of Washington are rural, yet housing in all these states is far more expensive than it ought to be. Only a few county-sized states — Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island — are more than 30 percent urban and none of them are less than 62 percent rural. Despite these facts, people such as Edward Glaeser, Linda Smith, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez never consider ending growth-management rules that are the true source of housing shortages.

These insane growth-management plans created entirely predictable housing shortages in order to save things that are extremely abundant such as farms, forests, and open space. This nation uses only 25 percent of its agricultural lands for growing crops to feed ourselves, make ethanol from corn, and export food to other countries. American forests are growing far faster than we harvest the trees. And with 97.1 percent of the country as a whole being defined as rural by the Census Bureau, open space is hardly in short supply.

The emphasis so many of these writers place on multifamily housing is classism at its worst. “Density for thee but not for me” means density for the working class while the middle class still gets to live in single-family homes. English socialist C.E.M. Joad, whose writings helped inspire the Town and Country Planning Act, was up front about this, complaining that lower-class people wore different clothes and listened to different music than the middle class. This proved to him that such people could not appreciate the benefits of low-density housing so he proposed that all new housing be restricted to high-density development in “sharply defined areas.”

American density advocates are not so overt in their classism, but the results are the same. It is ironic that people like Senator Smith and Representative Ocasio-Cortez complain about rising wealth inequality yet the policies they support are what is causing it.

The issue is we have People who wanna Live in the cities we have already.

When issue is why are we not building new cities to accommodate them. I know grandiose of idea of building cities from scratch is questionable track record.

National capitals are uniquely appropriate for “building from scratch” because there are guaranteed jobs – the jobs of the national government.

Any other cities you build up from nothing will have a chicken-and-egg problem. No jobs, therefore no residents, therefore no jobs. But in this situation jobs will go where availability and energy is cheap.

Though not a direct analog, this reminds me of A Raisin in the Sun.

Thinking forcing density etc will address this problem is an article of faith. Also, the core assumptions and priorities of this belief system are irrational and absurd. For example, categorizing everything as farmland to prevent the development of much-needed rural housing. https://oregonpropertyowners.org/saving-a-pile-of-rocks-state-sues-to-protect-unfarmable-farmland-from-needed-housing-development/

O’Toole is right. We have plenty of land.

However not all land is the same. IF 100% of California was developed, some areas would be more expensive than others. Therefore you ALSO need to expand vertically to the sky.

Also, current land use code policies and lending makes outward growth more wasteful. These can range from single use zoning, parking minimum, arterial routes and other mandates.

We can grow in a more traditional fashion.

– Strong Towns Las Vegas

There is no such thing as “traditional” development. Cities are products of technology, economics, and human preference. Also, your fixation on the current fads of abolishing single-family zoning, parking minimums and restricting arterials demonstrates your lack of understanding of the situation. This isn’t SimCity. . .

How so?

There is a such thing as traditional development. What they mean is in guise of developed layouts of grid streets, tight urban corners. But before industrial revolution; traditional architecture could only accommodate natural building materials like wood, stone, brick and some iron all which was relegated to mere 3-5 stories and maybe 5-7 for a few specially built ones.

The industrial forces of Steam, steel and stockyards which turned our cities into ultra high density claptraps or disease, deprived sunlight and massive industrial filth and children in factories and families in tenements were quickly and swiftly supplanted by technologies that permitted greater accessibility. Namely Horizontal manufacturing, Telephones and electric power.

– Horizontal manufacturing allowed industry to quickly transition to new larger consumer products Namely automobiles; but any product these factories required Land, But since it made sense to live in proximity to their jobs; housing and communities sprung up in these new factory towns.

– The telephone mitigated cost doing long distance business by permitting near instantaneous money lending and resource acquisition. It also allowed businesses to expand by connecting managers and employees across vast distances eliminating need to centralize ALL your employees in one location, thus emerged the satellite office.

– Electric power eliminated need for direct steam power; only electric motors, though powered by steam; by separating factory production from dangerous steam machines and explosive boiler risks. With electricity; factories no longer needed to be located near major sources of water

Lecturing folks on “how cars are dangerous” fall on deaf ears because the risk is statistically very low. (That’s why car haters talk about 40,000 annual deaths without mentioning the context of this happening over 5 Trillion miles of driving; and not all deaths are fault of the driver)

Their criticism of cars contrasts with the unpleasant, threatening, disturbing, and disgusting aspects of city life that people are relentlessly exposed to until they say “enough” and then leave for more civil environments — albeit with marginally more dangerous transportation.