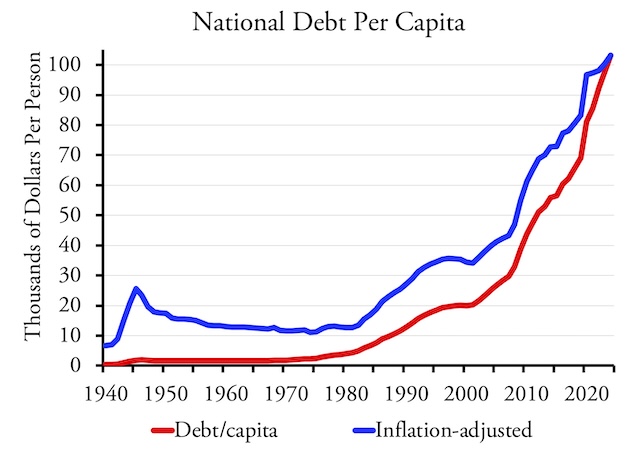

The national debt is more than $36 trillion, which is about $110,000 for every man, woman, and other-gendered person in the United States. When I was in high school, the national debt was about $1,800 per person, and I remember wondering if I could afford to pay my share. At that time, it might have been possible to pay it off with a one-time tax on everyone; today, not so much.

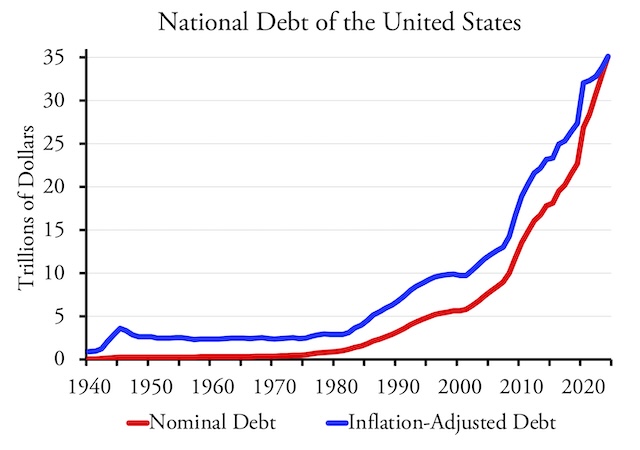

Before World War II, the U.S. had a long history of going into debt during wartime and then paying off most of that debt between wars. The above chart shows that after 1945 we paid off some of the war-related debt, but then entered a 1984-like world of permanent hot or cold war, which led Congress to give up any notion of completely paying off the debt. Still, as shown in the chart below, after adjusting for inflation the debt per capita continued to decline until around 1974.

Since 1974, the debt has grown increasingly out of control. The “Modern Monetary Theorists” who say this is perfectly healthy are as insane as anyone who thinks a diet of three all-you-can-eat meals a day at the Golden Corral could be healthy. The Department of Government Efficiency has the self-assigned task of reversing this trend, but to do so it needs to understand how we got here in the first place and why previous attempts to solve the problem failed.

Demographer Peter Zeihan blames it on the Baby Boomers. He points out that people consume in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, and that consumption leads to increased tax revenues for government. People save in their 50s and 60s, which provides the capital to support the consumer economy. After people retire, they become much more cautious with their savings, making little contribution to the economy or tax flows to government. As long as there is a balance of generations, however, the economy should work fine.

The large number of Baby Boomers created an imbalance. When they were young, they generated huge economic growth. In their middle years they provided the capital for such things as the digital economy. Now that they are retired or retiring, however, the economy threatens to stagnate.

So far that sounds reasonable. But Zeihan then says that the tax revenues generated by young Baby Boomers “allowed for the expansion of the government under Johnson and Nixon and Reagon. During this time, the Boomers, because the cash flows were robust, built a larger and larger welfare state” that mainly benefitted themselves. That welfare state can’t be supported now that the Boomers are retiring. The problem with this notion is that the national debt started going out of control in the mid-1970s, when Baby Boomers were still in their 30s. Why would increasing cash flows to government lead to increasing deficits? Zeihan offers lots of useful insights, but this isn’t one of them.

A Yale economist named Ray Fair blames the Baby Boomers for a different problem: a decline in infrastructure spending. Fair estimates that this decline began “around 1970” and that it represents a change that made the United States “less future oriented.” (In economic terms, the social discount rate increased so the future was less valued than the present.)

A less future-oriented country would help explain why deficit spending rapidly increased. If you don’t care about the future, it makes perfect sense to borrow and spend now. Fair speculates this happened because “the counterculture movement, triggered in large part by the Vietnam war and the draft, led to a change in tastes, in particular more negative views about the establishment and the government.” Infrastructure declined, Fair says, because people no longer trusted government. But if they didn’t trust government, then why did government spending increase so rapidly?

I don’t accept either Zeihan’s or Fair’s explanations. Instead, I think that budgetary trends reflect institutional designs. Sometimes, little changes can make big differences. The development of air conditioning in the 1930s allowed Congress to spend money year round instead of just the few months of the year when Washington wasn’t a malarial swamp. This helps explain the New Deal expansion of government.

During World War II, Congress started collecting income taxes as payroll deductions, rather than having people write a check at the end of each year. This made it possible for Congress to (almost) painlessly increase tax rates, since most people only saw their after-tax pay. This change contributed to soaring spending after the war.

A 1964 book by Aaron Wildavsky titled The Politics of the Budgetary Process explains how budgets were written before things started going out of control in the 1970s. Wildavsky noted that federal budgets resulted from negotiations between agencies, the president (often represented by the Office of Management and Budget or OMB), and the House and Senate appropriations committees.

The federal agencies usually asked for large budget increases; the OMB trimmed their budgets back; the Senate Appropriations Committee acted as an “appeals court” for agencies that wanted more money than the OMB recommended; while the House Appropriations Committee saw itself as the “guardian of the public treasury” and worked to scale back the budgets. The result, said Wildavsky, was a balance of power that provided the funds the government needed but kept budgets within reason.

The fiscally conservative nature of the House appropriations committee reflected the seniority system that selected committee members and chairs. Representative would have to be in office for several terms to be put on a powerful committee such as appropriations and even more to become the chair of such a committee. Voters in the South were more likely than their northern counterparts to repeatedly reelect their Congressional representatives, so southerners tended to dominate the appropriations committees.

Southern members of Congress were racists, and they used their power to prevent the passage of civil rights legislation. But they were also fiscal conservatives, and they used their power to slow the growth of government.

Then came the 1974 election. The Watergate scandal was so big that that election saw one of the largest turnovers in Congressional history. The newcomers were mostly northern Democrats who were angry at southern Democrats for holding up passage of civil rights bills. To take power away from those presumed racists, the newcomers changed the rules for how members were appointed to and made chairs of committees. Essentially, it became a popularity contest, and the best way to be popular within Congress was to support more pork barrel in other members’ districts.

Thus, the balance of power that Wildavsky found in 1964 disappeared a little more than a decade later. After that, the only force trying to restrain the budget was the OMB, and it was often overruled by the president, as when Reagan overruled OMB director David Stockman, leading the latter to resign in 1985. Since both the House and Senate were eager to increase spending and the OMB doesn’t have a vote in Congress, the gloves were off. In short, today’s debt can be traced to Watergate.

There have been a couple of attempts to reduce the size of the federal government since then. As noted here last November, the Clinton Administration tried to “reinvent government,” but its efforts lasted only a few years. The Tea Party movement saw the election of many fiscal conservatives, but they failed to gain a majority in Congress.

I hope that DOGE can do better at reducing the size of government, but I fear it will fail unless it understands this history. Most importantly, the history shows we need some kind of institution that will actively fight to restrain government spending and somehow balance its power against the pork-barrel tendencies of the House and Senate appropriations committees.

One way would be to turn DOGE into a permanent agency funded exclusively out of the money it saves by stopping wasteful programs. The agency might get 1.0 percent of the money it saves by ending existing government programs and (because it’s easier to stop new programs than kill existing ones) 0.1 percent of the money it saves by stopping new spending proposed by other agencies that passed OMB scrutiny or that had been approved by one house of Congress. If safeguards can be included to make sure it doesn’t covertly support wasteful programs just so it can enhance its budget by killing them, this could create a new balance of power.

The idea for such a predatory bureaucracy was first proposed by Montana political economist John Baden. “Ecosystems that lack predators become dangerously unbalanced,” Baden observed. “Introducing a predator into the U.S. Treasury ‘ecosystem’ is an idea whose time has come.”

Decades ago, our social studies teacher told us that we never have to pay off the national debt because, “The United States will go on forever.”

As a 12 year old, I saw both the truth and fallacy of that statement.

Which reminds me of the great Frank Zappa/Mothers of Invention tune, “It can’t happen here.”

A huge problem, not necessary conflicting with the analysis above, is that the Republican party came to believe that cutting taxes paid for itself in spite of abundant evidence to the contrary. They started cutting taxes and then just voting increases in the budget deficit to pay for spend voters demanded. Regan cut taxes and the deficit soared and he couldn’t get congress to cut spending. Then the nonsense of President George HW Bush mouthing “no new taxes” even when we went to war in Iraq for the first time. The deficit soared again. Finally Clinton vetoed tax decreases and finally the deficit was stemmed, see the graph above. The Republicans hated him for it and as soon as George W. Bush was elected started to cut taxes and run up deficits again. Then as politicians realized that voters didn’t care and both parties have been deficit spending. So far all Trump shows all signs of making the deficit producing tax cuts permanent and undoubtedly will sign into law deficit increases that will eventually bankrupt the country. Best to at least have the incentive that increased spending means increased taxes.

Peter Zeihan hopefully knows that far too many boomers became the problem they are because of inflation. if inflation were 0.5% instead of 5%, their house would not appreciate in nominal dollars and they wouldn’t see the need to seek bonds and metals for protection from inflation. metals should be a very small amount of normal investing (1%?) and government bonds should be illegal. But…

We all live in a world of comparative massive inflation which distorts where money is allocated in order to hopefully not run out of money before a person runs out of life on earth.