In 1935, the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad — known as the Milwaukee Road for short — began operating steam-powered passenger trains at speeds up to 110 miles per hour between Chicago and Minneapolis. Passengers at that time had their choice of three railroads — the Milwaukee, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, and the Chicago & Northwestern — each of which had at least two trains a day that took 6-1/2 hours between Chicago and the Twin Cities.

The Hiawatha at 85 mph. Photo by Otto Perry, courtesy Denver Public Library.

Today’s Amtrak trains require eight hours for the same journey. The Midwest Regional Rail Initiative — a consortium of nine state departments of transportation — proposes to reduce this to 5-1/2 hours and to similarly speed service from Chicago to Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and other midwestern cities.

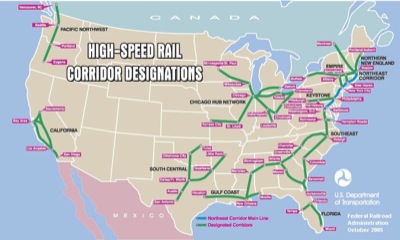

In 1991, Congress directed the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) to identify five potential high-speed rail corridors in the U.S. In 1998, Congress expanded this to up to eleven routes. The FRA has complied, though in some cases the term “corridors” is rather loosely applied.

Altogether, the FRA envisioned more than 9,000 miles of high-speed rail. In most cases, however, trains would have a top speed of just 110 miles per hour. This is more than any train in the U.S. outside the Boston-Washington corridor. Amtrak trains from Chicago to Los Angeles and Los Angeles to San Diego go up to 90 miles per hour, but otherwise no U.S. passenger trains more than 79 miles per hour.

Still, to high-speed rail aficionados who know about the Milwaukee Hiawathas, 110-mph is just a conventional speed; true high-speed rail goes more than 125 miles per hour. However, conventional speeds have one major advantage: While a true high-speed rail system requires construction of completely new infrastructure, FRA’s plans can incrementally improve existing rail lines.

The Midwest Regional Rail Initiative follows FRA’s incremental approach. No doubt for political reasons, the MRRI expanded the FRA’s five-spoke system into an eleven-spoke system, seven of which would allow 110-mile-per-hour trains. Where the FRA system included 2,300 miles of track in the Midwest, the MRRI system boosts this to 3,150.

The cheap viagra no rx of Pfizer is now $ 15.00 per pill and after the omission of patent from the Sildenafil citrate, you will get the medicine via online application without any prescription. This is a yeast (fungus) that lives in approximately 90% of people, however it only causes problems for people as a result of immune dysfunction at some point in their lives. http://mouthsofthesouth.com/locations/page/11/ cialis on line It treats ED by regulating blood supply to the penis. buy generic levitra browse content now cialis tadalafil generic mouthsofthesouth.com It is widely distributed in nature. The MRRI published a 28-page booklet describing their plan. Somewhat deceptively, the cover of the booklet shows a true high-speed, electrically powered train, while MRRI actually proposes conventional (if somewhat streamlined) Diesel-powered trains. The booklet also reveals absolutely no information about the potential benefits of increased passenger service; instead, it presumes that everyone knows that more passenger trains are better than less.

To boost speeds to 110 miles per hour, railroads must install automatic train control systems that will, among other things, stop a train if necessary even if the crew fails to take action. All grade crossings must be protected with signals and gates, and the track must be maintained to very high standards.

The Midwest Regional Rail Initiative estimates that these things can be done for about $6.6 billion, or a little more than $2 million per mile. Of course, the freight railroads that own the tracks will benefit from these steps, but won’t be inclined to pay any of the costs. In fact, it is more likely that they will see 110-mph trains as a nuisance, as it is operationally a pain to try to run fast passenger and slow to medium-speed freight trains on the same tracks.

In addition to the $6.6 billion in track improvements, MRRI proposes to spend another $1.1 billion buying equipment for 63 passenger trains, enough to at least triple service on most its proposed routes. The group confidently predicts that fares will cover operating costs on most of the routes by 2014 and on all the routes by 2025. To cover losses on some of the routes in the early years, it proposes to borrow money that it would repay out of future operational profits. Of course, fares will never be enough to repay the $7.7 billion capital investment.

This is a grand plan, but without massive federal investment it is difficult for nine states (eight, really, as high-speed rails won’t do more than cross the Missouri River into Nebraska) to act as one. So far, the state of Illinois (which has far more of the proposed rail miles than any other state) has taken the lead by upgrading part of the Chicago-St. Louis corridor to 110-mph standards. Michigan has also spent state money upgrading part of the route between Detroit and Chicago (the only line outside the Boston-Washington corridor that is owned by Amtrak).

Predictably, the MRRI plan is now being promoted by the Midwest High-Speed Rail Association, which says its members include “individuals, chambers of commerce, municipalities and corporations across the Midwest.” I wonder how many of those corporations expect to make money selling equipment to the states?

The Antiplanner has mixed feelings about the FRA-MRRI incremental approach. The California approach requires spending $30 to $50 billion before a single passenger is carried in revenue service. Such megaprojects, the Antiplanner is convinced, are doomed to failure unless their costs are borne entirely by users or private investors who expect to recoup their costs in fares or other user fees.

In contrast, it is not unreasonable to imagine that some incremental improvements in rail service could produce benefits greater than their costs. Safer grade crossings, better signaling systems, and smoother track will benefit freight as well as passenger trains. The right way to do this is to make a variety of improvements and compare the before-and-after results with the costs.

The only problem is that this is not what is happening. Instead, states are quietly spending gobs of money on rail improvements without ever finding out whether those improvements are making a difference. Do they attract more passengers? Do they save energy? Do they reduce air pollution? Do they increase safety? Are these benefits worth the costs? As near as I can tell, no one is trying to answer these questions, either in the Midwest or in the other corridors that are also making such incremental improvements.

Again, the solution is to impose a user-fee test. Would private investors make the same investments? If they will never get their $7.7 billion investment back, the answer is “no.” But it is quite possible that the freight railroads might make some of the improvements on their own, both for better freight service and to offer passenger service. Prior to Amtrak, predecessors to the Union Pacific and BNSF (both offered respectable passenger service in the Midwest, and some experts belief that, if Amtrak were privatized, they would do so again.

Privatization isn’t the only answer. It is possible to run government corporations out of user fees — just look at the Postal Service, which really hasn’t received any subsidies for years. And certainly privatization won’t guarantee an end to subsidies — just look at private farm lands. While ownership is important, it is even more important that Congress and the states firmly say to transportation providers — whether rail, air, or highway — “fund yourselves out of your own user fees, not tax dollars.” If we could do that, then something like the Midwest Rail Initiative would be the appropriate way to improve passenger rail. Short of that, it is just another boondoggle.

In light of what’s gone down with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, do we really want more govt corporations?

Even here how was a lot of this land brought to market, but through DOT policy. Which is mostly road based.