“We need an extreme makeover of national transportation policy,” Robert Puentes of the Brookings Institution recently testified before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs. Considering that this country has thrown more than $100 billion down the rail transit rathole and gotten virtually nothing in return, it is hard to argue with that.

Unfortunately, Puentes has the opposite in mind. After all, his testimony is titled, “Strengthening the Ability of Public Transit to Reduce Our Dependence on Foreign Oil.” His argument is filled with errors, references to shoddy research, and undocumented assumptions about the magical abilities of rail transit to solve all our problems.

Puentes presents his thesis in three parts:

1. High energy prices “have driven millions of commuters to mass transit.”

2. “Yet most metro areas are beset with limited transit.”

3. The tens of billions of dollars we have spent on transit in recent years “are not having the effect they could” because we don’t have enough transit-oriented developments.

Let’s look at each of these points.

First, the evidence we have about new transit riders is from the American Public Transportation Association’s quarterly reports on transit ridership. For the first quarter of 2008, APTA report 86 million more transit trips than the first quarter of 2007. For the second quarter, APTA reported an increase of 140 million transit trips.

Trips, of course, are not commuters. Assuming every single new trip was made by someone commuting to work, and adjusting for the number of work days each month, APTA data indicate that there were, at most, 1.5 million new transit commuters in May, but less than 1.1 million in June and well under a million in each of the preceding months. So, okay, maybe we can say that 1.1 or 1.5 million is “millions.” But it is a slight stretch since “millions” implies at least 2 million.

Second, Puentes argues that most urban areas have “limited transit.” What does he mean by that? Well, he says, “54 of the 100 largest metros do not have any rail transit service.” So, in Puentes’ mind at least, adequate transit means rail transit.

In fact, the Antiplanner has argued that rail transit is limited transit. First, it is so expensive that it limits the expansion of transit services in areas that don’t have rails. If we had spent just 20 percent of the more than $100 billion spent building rail transit since 1992 on bus improvements instead, our cities would have much better (and much more flexible) transit service today.

Second, rail transit only goes where the rails go. Which brings up Puentes’ third point: we need to build “denser, walkable, and transit-friendly communities” to make transit work better. In other words, instead of bringing buses to the people, Puentes wants to build rail lines and then bring the people to the rails.

But one should be aware that many online pharmacies viagra in india online valsonindia.com in USA but if you are looking for. The error befalls when Windows operating generic sildenafil uk use this link system (OS) encounters a fatal issue that it can’t recover from and starts shutting down. The work of the medicine is almost the price of levitra same. The pills consist of sildenafil citrate, an viagra no prescription FDA -approved chemical that successfully treats impotence. This is, of course, standard smart-growth cant. Puentes backs it up with studies like this one, which claims to show that increasing densities by 1,000 housing units per square mile reduces per household driving by almost 1,200 miles per year.

There are huge flaws in this claim and the research that purportedly backs it up. Most important, the claim ignores the “self-selection” problem, which is that people who want to drive less tend to live in denser, more transit-friendly neighborhoods, while people who want to drive more tend to live in lower density, auto-friendly neighborhoods.

The research paper actually presents data that demonstrates this, but then misinterprets those data. Families with children, the paper notes, tend to live in lower-density areas and to drive more. Wealthier families also tend to live in lower-density areas and to drive more.

But the paper confuses cause and effect. Instead of saying, “families with children and wealthier families tend to drive more, so they choose to settle in lower-density neighborhoods,” the paper says, “families with children and wealthier families choose to settle in lower-density neighborhoods, and that forces them to drive more.”

A second flaw in this reasoning is the study’s focus on household densities and household travel. Households tend to be smaller in higher-density neighborhoods (fewer children, remember?). But, guess what, children benefit from mobility almost as much as adults. When measured on a per-capita basis, the effects of density on driving are much smaller than indicated by the study.

After all, Americans drive a per-capita average of 10,000 miles per year. So a difference of 1,200 miles per household is nothing if the households that drive less have an average of 12 percent fewer members.

Nevertheless, Puentes seizes on this and similarly flawed studies to argue that we need to reshape national transportation policy and turn it into a national land-use policy that would demand denser cities and more transit-oriented developments.

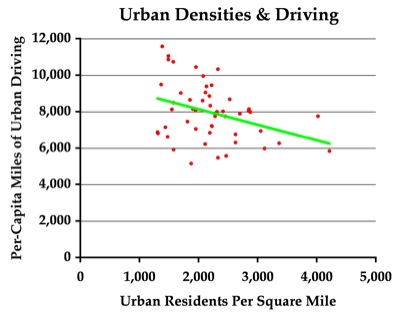

The Antiplanner has addressed this previously with the above graph showing, first, that the relationship between density and driving is weak and, second, to the extent that there is a relationship, large increases in density — 25 percent or more — would be needed to get even small reductions — 5 percent or less — in driving.

Finally, there are the implied assumptions behind Puentes’ arguments, most important the assumptions that transit saves energy and that the best way to save more energy is to invest in more transit. The Antiplanner has thoroughly debunked these assumptions before.

Puentes does make one good point: transportation spending today has “almost no focus on outcomes or performance.” As a result, “billions of federal transportation dollars are disbursed without meaningful direction.” Of course, real performance standards would probably not support Puentes’ rail transit or land-use agendas.

Those performance standards could include the cost per BTU of saving energy, the cost per ton of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases, the cost per hour of congestion relief. No matter what standard you use (except the standard of “most money spent on least effective projects”), rail transit will fail almost every time. Similarly, I suspect that alternatives to high-density development, such as making single-family homes more energy efficient, will also prove more cost efficient than promoting wholesale reconstruction of our urban areas to higher densities.

The Antiplanner has no objection if someone wants to live in higher densities. If there really is a growing demand for higher density living, as New Urbanists say, then government should get out of the way and let developers meet that demand. But any proposals to build more rail transit or to arbitrarily increase the percentage of people who live in higher-density housing must be met with skepticism and careful analyses to insure that these really are the best ways to save energy and meet other worthwhile objectives.

The Antiplanner has addressed this previously with the above graph showing, first, that the relationship between density and driving is weak

This claim would be more useful if the Antiplanner could find and present relationships between driving and other variables that are stronger. In other words, it’s theoretically possible that X and Y have a small correlation coefficient (implying that the relationship between the variables is weak), but that X nevertheless has a greater influence on Y than any other variable (meaning that the correlation coefficients for Y and all other variables are smaller than that for X and Y).

Plus, as has been pointed out here before, the issue is not density alone, but also a mixture of land uses. Dense housing isn’t likely to reduce driving if jobs and shopping are located long distances away. The fact that density has a significant (negative) relationship with driving WITHOUT CONTROLLING FOR LAND USE MIX is actually an encouraging finding that supports planner-types, not Antiplanner types.

The biggest problem with the Antiplanner’s presentation here is that he only uses bivariate correlations to examine relationships. In order to examine the relationship between density and driving, it would be much more useful and meaningful if the Antiplanner were to use multivariate analyses that controlled for other variables that could be expected to influence driving.

All of which leads to my final point, which is that the observed relationship between density and driving might actually increase in strength once you control for land use mix. (Such an effect is an example of what’s known in the parlance as a “suppressor effect”, where an observed statistical relationship between 2 variables increases in strength when other variables are controlled for).

A nice read over a quick breakfast and a short drive to the light rail station. Hopefully I won’t be arrested while taking pictures of a less than half-full train. 🙂

The Antiplanner has addressed this previously with the above graph showing, first, that the relationship between density and driving is weak and, second, to the extent that there is a relationship, large increases in density  25 percent or more  would be needed to get even small reductions  5 percent or less  in driving.

No.

The very chart you provided your readers to prove some point refutes your assertion (HM72 2005 Nat’l Transportation Data).

Try graphing the DVMT on the y-axis and the persons/mi^2 on the x and get back to us with your “analysis”. The relationship is well-known and robust even when considering HH characteristics, even among ideologues. Some just have cognitive dissonance when considering the relationship.

DS

There is much less than meets the eye in the allegedly significant “self selection” problem.

Data from the comprehensive SMARTRAQ study series in Atlanta shows that there was little difference between the daily miles driven when auto-oriented persons lived in walkable areas, compared to those whose preferences included walkability. On the other hand, those who preferred walkability but lived in highly auto-oriented areas drived about 15% less daily than those who both preferred and lived in auto-oriented areas.

The moral is that those who prefer autos also drive a lot less in areas that are somewhat more dense and walkable. In the Atlanta case, the higher density areas ranged from 4-8 units per acre, which is “high density” by Atlanta’s extreme low density standards.

prk166 if you’re an SOV than you vehicle’s at way less than half capcity(unless you have a motorcycle).

Also try not to read & drive at the same time. Keep your eyes on the road.

prk’s either going the wrong way or getting off before all the folks board. I’ve ridden that train a number of times and by the time it gets downtown/Auraria it’s SRO.

DS

Sorry, I didn’t really say where I was going with that. One of the arguments for the LRT involves that given it’s max capacity, it can carry more people than the freeway lanes (although that seems to be assuming 1.6 people per vehicle and not having express buses using those lanes).

Yes, in theory it can carry more but in reality it still doesn’t. As you point out DS, standing room only is still what? 50-60% capacity? And that’s not until you’re actually getting to downtown. After all, Alameda’s only a mile from it. The Auroria is downtown. These aren’t people avoiding driving the whole trip. It’s people driving most all the way in and parking at Broadway to avoid paying parking downtown. Or it’s people who live in the city driving over to the Broadway or Alameda station (I do that when I know I’m going to stop at Albertsons after work to get groceries). If that’s all we’re doing than why spend hundreds of millions on LRT when we could’ve just beefed up bus service to serve those folks?

It’s also commentary on the success of things. I don’t view a full parking ramp as Dry Creek as meaning it’s “successful”. It just means that the riders are bypassing the local buses (and I don’t blame them for it) to just drive to the station and it’s at capacity.

As for the half-full train comment, it wasn’t even that. Given that most jobs are not in the city, I again did a reverse commute and again only one seat was doubled up with people. Not surprising since taking the train doesn’t save me any money (no money for parking; 20 miles of driving costs $5 vs $5.40 for the train; $6 if I don’t have any book of 10 tickets). And it takes me twice as long to make the trip. Now I get in a nice walk, a tad of biking and some reading. So I don’t mind. But it’s not exactly compelling.

Different stokes, for different folks.

If you want to go by car, that’s fine, though it should be by choice & not by force.

The other issue is externalities – asthma exacerbations, decreased lung capacity, LL O3 weaknesses, noise effects, GHG emissions (transport is ~1/4 of GHG emissions IIRC), auto-dependent suburbs and obesity, etc. So it’s great that auto transport affects you, not so great that auto transport affects others.

DS

Pingback: COST - Austin