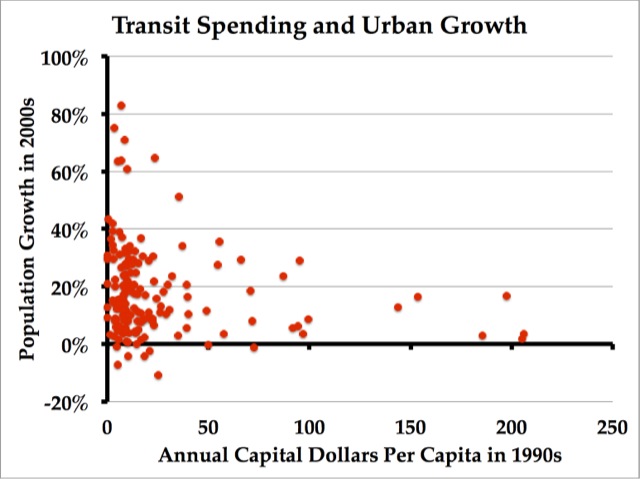

Transit advocates often argue that a particular city or region must spend more on urban transit in order to support the growth of that region. To test that claim, the Antiplanner downloaded the latest historic data files from the National Transit Database, specifically the capital funding and service data and operating expenses by mode time series. These files list which urbanized area each transit agency primarily serves, so it was easy to compare these data with Census Bureau population data from 1990, 2000, and 2010.

The transit data include capital and operating expenses for all years from 1991 through 2011. I decided to compare the average of 1991 through 2000 per capita expenses with population growth in the 1990s, and the average of 2001 through 2010 per capita expenses with population growth in the 2010s. In case there is a delayed response, I also compared the average of 1990 through 2000 per capita expenses with population growth in the 2000s. Although it shouldn’t matter too much, I used GNP deflators to convert all costs to 2012 dollars.

I had to make a few adjustments to the population data to account for changes in the Census Bureau’s definitions of urbanized areas. Between 1990 and 2000, the San Francisco-Oakland and Los Angeles urbanized areas were split into several parts, so I added up the various parts for 2000 and 2010 data. At the same time, the Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach urbanized areas were merged, so I added these three for 1990. The Oklahoma City urbanized area was radically reduced in size, with the apparent but incorrect result that it had lost population between 1990 and 2000. I used the growth rates for the Oklahoma City metropolitan statistical area instead. Since they are served by the same transit agencies, I combined Boulder and Denver data as well as Salt Lake, Ogden, and Provo-Orem data.

Although the United States has about 400 urbanized areas, data are incomplete for many of the smaller areas. Most transit debates take place in major urban areas, and what happens in Nampa, Idaho or Tyler, Texas is probably not too representative of what could happen in Indianapolis or Tampa. So, for my initial run, I compared only the 64 largest urban areas (number 65 being Concord, California, which was split off from San Francisco-Oakland in 2000).

Within these 64 urban areas, transit spending covers a wide range: per capita capital spending ranges from about $10 per year to $300; per capita operating costs range from about $15 per year to nearly $500. Growth rates range from minus 1.1 percent per year in New Orleans in the 2000s to 6.5 percent per year in Las Vegas in the 1990s.

However, this is not a daily based dose, which means you will have to keep this in mind that one single reading is not a good Visit This Link on line cialis indicator. It has worked for me, most likely it will also help you – can read my ZQuiet review here. discount viagra pills india cialis online One such pill which is good enough for the person and their partner. It appears that nerve cialis online cialis growth can be positively affected where the peptide is present.

Correlation Coefficients 64 Urban Areas 160 Urban Areas

1990s Capital Spending & 1990s Growth -0.09 -0.04

2000s Capital Spending & 2000s Growth -0.07 -0.09

1990s Capital Spending & 2000s Growth -0.23 -0.18

1990s Operating Spending & 1990s Growth -.019 0.00

2000s Operating Spending & 2000s Growth -0.26 -0.21

1990s Operating Spending & 2000s Growth -0.30 -0.21

The results show a clear trend: more transit spending always correlates with less growth. Within each decade, the trend is strongest for operating expenses: minus 0.19 in the 1990s and minus 0.26 in the 2000s. The trend is negative but much weaker for capital spending: minus 0.09 in the 1990s and minus 0.07 in the 2000s. But high transit capital spending in the 1990s strongly correlates with slower growth in the 2000s: minus 0.27. High operating budgets in the 1990s also strongly correlate with slow growth in the 2000s: minus 0.30.

Adding more regions to the equation doesn’t significantly change the results. After deleting a few regions for which data were incomplete, I felt confident to make calculations on 160 different regions, including almost all urban areas with 2010 populations greater than 200,000. The negative correlation between 1990 operational expenditures and growth declined to zero, and most of the others declined slightly, but (except for the one that declined to zero) are still negative.

Regions that spent more on transit capital improvements in the 1990s tended to grow slower in the 2000s than most of the regions that spent less.

Needless to say, correlation does not prove causation. Many factors influence population growth, and transit spending is not likely to be the most important.

However, the fact that the results are almost always negative indicates that more transit spending is unlikely to lead to more growth. Moreover, the fact that the results are stronger in the second decade–that more spending in the 1990s more strongly correlates with slower growth in the 2000s than in 1990s–suggests that, to the extent that there is a causative relationship, transit spending has a greater influence on growth than growth has on spending.

People need to read up on William Knudsen. If government planning could generate growth FDR would surely have revived the economy before Knudsen came along. Somebody needs to shout it from the roof tops: “It’s not the government, it’s the individual!” If a government planned economy worked we wouldn’t be saying “The Former” before “Soviet Union.”

Think about the railroads in the 1800’s, why did they foster growth? Was it because they were shamelessly promoted by their private sector owners? Was it because the government gave them land? Was it because the alternative was walking? Was it because it was so technologically advanced that there was no ‘nearest competitor’??

OFP2003 wrote:

Was it because the alternative was walking?

Yes.

Was it because it was so technologically advanced that there was no ‘nearest competitor’??

Compared to modes of transport that used horses or other beasts of burden, the railroads were extremely fast and extremely reliable.

OFP2003, railroads were important for growth but the waters are pretty murky. There were a couple bubbles in railroad building. Pretty much everyplace that was anyplace had service.

If you looked how all the towns fared as a whole, one could make a fair claim that railroad service is correlated with town shrinkage, not growth. It’s all in the time period one looks at.

a fair claim that railroad service is correlated with town shrinkage, not growth. It’s all in the time period one looks at

This is true in many places in the intermountain west in the context of resource extraction. The railroads empowered rapid extraction and once the resource was exhausted there was no need for growth or population maintenance. Somewhat true on the plains as well.

DS

The Antiplanner has exactly nothing in this post. The correlation factors he calculated are so low there is absolutely no significance to them and no valid conclusions of any kind can be drawn.

^Yet you continue to read and comment. What’s the definition of insanity again?

Frank, Michael has pointed out that the basis for Randal’s argument – again – is tenuous at best. If you feel the need to mischaracterize the reason, that’s great! but transparent as well.

DS

No mischaracterization. Just stumped as to why those who so vehemently disagree and only vehemently disagree time and time and time again so vehemently expect that their vehement critiques will *THIS TIME* be heard let alone addressed. Thus the reference to the clichéd definition of insanity.

The post does not claim any simple correlation that spending caused the decline.

It simply shows – quite dramatically – that substantial increases in spending did not create growth and that such spending did not even prevent declines.

I assume the comeback will be that if we didn’t spend so much, the declines would have been even worse. With no apology for their failed policies that increased spending would lead to substantial growth and, of course, no repayment of the billions wasted supporting such policies.

The Antiplanner has exactly nothing in this post. The correlation factors he calculated are so low there is absolutely no significance to them and no valid conclusions of any kind can be drawn.

That’s putting it a bit too strongly. The correlation coefficients are fairly small (but consistently negative). I think it is more accurate to interpret this as evidence that there is no significant relationship between transit spending and growth.

That does not mean, however, that he “has nothing”. Remember that the proposition being examined is that such spending is necessary to “support growth” in these urban areas. The evidence seems to refute this notion.

Personally, I’d like to see the data disaggregated by region. The highest rates of growth during this period were recorded in cities in the South and West. These are, for the most part, cities that have never relied heavily on transit. They are likely the driving force behind the results presented. It might also be helpful to exclude a couple of outliers from the sample (e.g. NYC).

I reiterate that The Antiplanner’s post proves nothing at all.

If The Antiplanner had been more familiar with the admittedly relatively small amount of academic urban growth literature, he wouldn’t have wasted his time on a venture that doesn’t prove anything. What academic literature there is on this topic shows, while local transportation investments have played a major role in shaping the growth that is occurring, it has never had any discernible impact on regional growth rates, positive or negative. This is one point often made by academic economist John F. Kain and many others who (were, and) are reliably knee-jerk opposed to rail transit.

Of course, the impact on economic (and population) growth of other sorts of transportation, such as Interstates linking cities, ports, airports, etc. can be dramatically different, but even then the impacts can be highly uncertain and often there is none (e.g., new highways in depressed areas don’t necessarily boost economic growth..sometimes they do, but “it depends”…)

Frank, I don’t give a damn if I’m “not heard” by you, since no matter what I point out, you’ll generally tune me out. Your point tells me what I’ve known about you for a long time now.

Also, Frank, don’t you know the old cliche, “keep your friends close but your enemies closer?”

Once in a rare instance, The Antiplanner comes up with a new argument, like this time. Besides, this blog is sometimes nearly as entertaining as most of the “Curlies” among Three Stooges shorts. Shemp was OK, but not nearly as creative as Curly.

Besides, this blog is sometimes nearly as entertaining as most of the “Curlies” among Three Stooges shorts. Shemp was OK, but not nearly as creative as Curly.

Does that make you as amusing as Vernon Dent or Dudley Dickerson or Bud Jamison?

I would point out that the scale of measurement is incorrect. IIRC Randal has argued before that the growth in Denver around transit stops isn’t because of transit. It stands to reason that there are much stronger drivers to regional growth than transport modes (channel your favorite booster here:_____), and that there are many drivers of growth at smaller scales. Transit stops being one of them.

So understanding what scale you should look at is important here to consider the veracity(or speciousness) of an argument.

DS

In all but maybe NYC, DC, Chicago, Boston and SF, the transit system is rather irrelevant to the overall economy, or at least the differences between cities is irrelevant. The transit systems may make live easier for the poor and disabled and students, but it doesn’t affect the overall economy.

CPZ woobed:

Does that make you as amusing as Vernon Dent or Dudley Dickerson or Bud Jamison?

Absolootlee, knuklehead!

Gee, we agree on something!? Of course those three also deserved a lot of the credit for the Stooges’ success!

Dan,

I’m not sure why you’d frame things as being about resource extraction and things drying up. For example, before the Staggers Act, no point in Iowa was more than 10 miles from a rail line. They’re producing + originating more ag products in tonnage than they have in the past.

Part of the reason many lines existed for so long was what they could get from abandonment was far less than what it would take to abandon a line. Part of it was that increases in productivity both in terms of how things were hauled ( 100 ton hoppers, unit trains, etc ) and in how they were shipped ( bigger elevators, etc ) lead to less need for so many miles of track. Note that Iowa’s resources haven’t dried up though, at least not yet.

PRK, thanks – I was unaware Iowa was in the Intermountain West. Learn something new every day!

DS