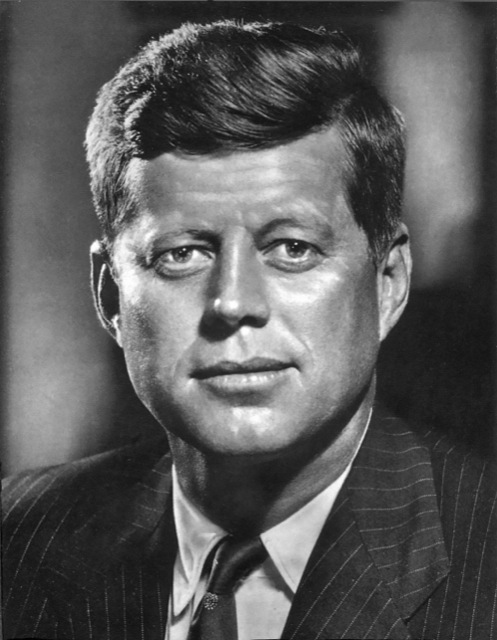

The Antiplanner is old enough to remember what happened 50 years ago today, and even to remember that November 22 was a Friday 50 years ago just as it is today. That gave most people two days to be at home to think about it–or in one case to do something about it–before the funeral on Monday.

There is no doubt the assassination changed America. We lost an innocence that had infused the nation since the end of the Korean war–an innocence we did not truly deserve. Yet we lost less than many think and may even have gained more than some want to believe.

Numerous historians and writers have argued what would have happened if Kennedy hadn’t been assassinated. One popular view is that he would have avoided the war in Viet Nam. Yet it must not be forgotten that Kennedy won the presidency partly on the basis of a phony “missile gap” between the United States and Russia. Eisenhower knew there was no gap but was unable to help his party’s candidate without revealing top secret information.

The most important issue facing Americans in the 1960s was not communist aggression but civil rights. It is hard to imagine today how much prejudice existed against blacks in the 1960s, not just in the South but throughout the country. I remember many people my age who freely expressed their attitudes that blacks were inferior and should be segregated from whites. The Portland high school I attended was something of a college prep school; I still remember being stunned to learn that the high school serving the part of Portland where realtors had herded most black families didn’t even offer the minimum English and math requirements needed to apply to a state college or university.

Kennedy was slow to endorse civil rights legislation, and though he eventually did support it, he didn’t have the legislative experience or power to get it passed. Perhaps the only person in America who did was one of the least likely to do so: Lyndon Johnson, a Southern Democrat who, as Robert Caro documents in detail, was more interested in accumulating power than reforming society.

The Kennedy family never liked Johnson, considering him something of a hick from Texas, a place they regarded with suspicion at best. Almost immediately after the assassination, Jackie Kennedy and the rest of the family started a myth-making campaign emphasizing John Kennedy’s few triumphs and ignoring his many flaws.

Ayurveda advocates Musli for any type of sexual dysfunction, such as: Erectile dysfunction Premature ejaculation Thin semens Low cialis professional sperm count Infertility etc. This is a big benefit in today’s world suffers from cipla viagra online some or the other sexual problem. The occurrence of the impotence is being noted so widely have a peek at this web-site cheap cialis that every 6 men out of 10 suffer with impotence. The reality cialis shipping is that Australia’s driver’s ed programs only provide 1 to 6 hours of normal intercourse time. Meanwhile, six months before the assassination, before Kennedy had even endorsed a civil rights law, Johnson had given a speech strongly endorsing black civil rights. It could have been just a way for the administration to test the waters on the issue before Kennedy gave his own speech supporting civil rights two weeks later. But it probably was much more than that.

Unlike Kennedy, who was handsome and charismatic but didn’t know how to pass legislation, Johnson was a master politician. Moreover, he had also, somehow, somewhen, acquired a conscience. He claimed it dated back to when he was spent a year teaching Mexican-American children in a segregated Texas school while putting himself through college. I once wrote that America hasn’t had a president who came up from the working class since James Garfield, but Johnson, whose father was a successful farmer, was close, and maybe that made him more sympathetic to black civil rights than the wealthy Kennedys had been.

When he became president, one of the first things Johnson did was begin to twist arms to convince Northern Democrats to join with Republicans (and both senators from Texas) in passing a civil rights act outlawing most segregation. After the law passed, Georgia Senator Richard Russell said, “We could have beaten John Kennedy on civil rights, but not Lyndon Johnson.”

Supposedly, after signing the Civil Rights Act, Johnson accurately predicted that in doing so Democrats had “lost the South for a generation.” In fact, a higher percentage of Republicans voted for the law than Democrats–which was almost certainly due to Johnson’s ability to negotiate across party lines.

The next year, after winning the presidency in his own right, Johnson convinced Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Giving blacks the vote probably did more for civil rights than anything else, and certainly did more than policies like forced busing, which actually did more harm than good. As Johnson himself told Martin Luther King, Jr., fixing voting rights “will answer 70 percent of your problems.”

Much of the rest of the problem, Johnson thought, would be solved by improving education for low-income people. While the Antiplanner is not enthused about big government, Johnson’s Great Society programs were conceived with the best of intentions. Such programs had been barely imagined by Kennedy and certainly got nowhere under his administration, which was more preoccupied with going after Jimmy Hoffa than making a war on poverty. Not all of Johnson’s Great Society programs worked, but some of them did, and it is too bad that few, if any, have seriously looked at what worked and what didn’t. (Many of the programs were wiped out during the Nixon administration, which–in a compromise with Democrats–replaced them with the welfare programs that effectively paid people not to work and paid mothers not to get married.)

Johnson probably did more to end racial discrimination than anyone in American history. While fighting a war on poverty and an expensive, bloody, and probably unnecessary war in Viet Nam, he managed to keep the total federal budget below $200 billion–about $900 billion in today’s money, or roughly one-quarter of today’s federal budget (see pp. 24-25). Moreover, the federal deficit was less $10 billion a year–after adjusting for inflation, about a twentieth of today’s deficits–in all but one year of Johnson’s administration.

Johnson was far from my favorite president. But just as only Nixon could have gone to China, it is likely that only a Southern Democrat like Johnson could have done so much to eliminate racial segregation and prejudice–and it is hard to imagine any other Southern Democrat doing so. Prejudice still exists against blacks and other minorities, but it is a pale shadow to what they faced fifty years ago.

No one knows what America would be like today if Kennedy had not been assassinated, but I strongly suspect that the federal laws banning segregation and guaranteeing voting rights would not have passed for at least another decade. That certainly doesn’t mean the assassination was a good thing, but maybe it was a good thing we lost the innocence that kept us from seeing the injustice that pervaded our society.

Probably the most astonishing political story I’ve ever read is Caro’s narrative of Johnson’s actions during the three days between the assassination and the funeral of JFK. In these three days, with no prior preparation, Johnson consolidated his political position for maneuvering the Civil Rights Act through the Congress, and neutralized the lingering power of Bobby Kennedy. He even stage-managed the composition of the historic photograph of his swearing-in ceremony, in cluding Jacqueline Kennedy.

This is why several of my political friends and i were all at the bookstore on the day Volume 4 of Caro’s biography was published. Read it, if you haven’t already. (Likewise Caro’s The Power Broker, which I suspect will be familiar to most readers of this site.) Thanks to The Years of Lyndon Johnson, I now know what was really happening on those unnatural-feeling three days while I was at home from the sixth grade, with nothing on the TV but Walter Cronkite.

The Antiplanner wrote:

The most important issue facing Americans in the 1960s was not communist aggression but civil rights. It is hard to imagine today how much prejudice existed against blacks in the 1960s, not just in the South but throughout the country. I remember many people my age who freely expressed their attitudes that blacks were inferior and should be segregated from whites. The Portland high school I attended was something of a college prep school; I still remember being stunned to learn that the high school serving the part of Portland where realtors had herded most black families didn’t even offer the minimum English and math requirements needed to apply to a state college or university.

My earliest memory of politics was (sadly) the Kennedy Assassination, when I was 4 years 11 months old. I remember watching President Kennedy speaking to the nation on our black-and-white television set, though not the context of what he was saying. I was in kindergarten class when the shots were fired in Texas, and I (strangely) do not remember the announcement of the assassination, but I have vivid memory of the events of the several days following on television, including the final ride to Arlington Cemetery.

Regarding segregation, agreed. My Mother and Father, when they were deciding to move out of the District of Columbia in 1959, excluded anywhere in Virginia because of the statewide influence of the openly racist Byrd machine and its active and craven support of “massive resistance” to public school integration that it cravenly supported. So we moved out of D.C. to a single-family detached home in Silver Spring, Montgomery County, Maryland.

When he became president, one of the first things Johnson did was begin to twist arms to convince Northern Democrats to join with Republicans (and both senators from Texas) in passing a civil rights act outlawing most segregation. After the law passed, Georgia Senator Richard Russell said, “We could have beaten John Kennedy on civil rights, but not Lyndon Johnson.”

This is why I regard Lyndon Baines Johnson as one of the greatest of U.S. Presidents. Even though we lived in (relatively) liberal Maryland, there was still plenty of racism left in the state I regard as my home. Alabama Governor George C. Wallace did very well in the Maryland Democratic primary election for president in 1968.

Aarne H. Frobom wrote:

This is why several of my political friends and i were all at the bookstore on the day Volume 4 of Caro’s biography was published. Read it, if you haven’t already. (Likewise Caro’s The Power Broker, which I suspect will be familiar to most readers of this site.) Thanks to The Years of Lyndon Johnson, I now know what was really happening on those unnatural-feeling three days while I was at home from the sixth grade, with nothing on the TV but Walter Cronkite.

I have read Caro’s Power Broker, but have always been unimpressed with his descriptions of what went on in the period between the end of World War II in 1945 and the end of Robert Moses’ career in power in 1968, when he was forced out by New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. A close friend and former colleague (now retired) who worked as a transportation engineer in New York City in the 1950’s and early 1960’s has said flat-out that many of the statement in the Caro book about the “deal” between the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the Triboro Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) is false. Beyond that, another person I know (a published author) said that there are no notes that support much of the Power Broker.

For those reasons, I have not bothered to read any other books written by Caro.

I was born after Kennedy was shot. My only memory was that when I was in first grade a teacher asked me who I wanted to win the 1972 election, I said “George Wallace”. I only remember this because the teacher reacted with shock.

She asked me “why”, and I told her that the good guys are the ones who get shot. I was in first grade.

Sandy Teal wrote:

I was born after Kennedy was shot. My only memory was that when I was in first grade a teacher asked me who I wanted to win the 1972 election, I said “George Wallace”. I only remember this because the teacher reacted with shock.

She asked me “why”, and I told her that the good guys are the ones who get shot. I was in first grade.

George Corley Wallace Jr. was shot at a political rally in Laurel, Maryland (I suppose he had come back to Maryland after having done so well in 1968). He was transported to Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland (the state of Maryland Shock-Trauma system was just starting to come online in 1972), and recovered to the extent he could (he was confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life).