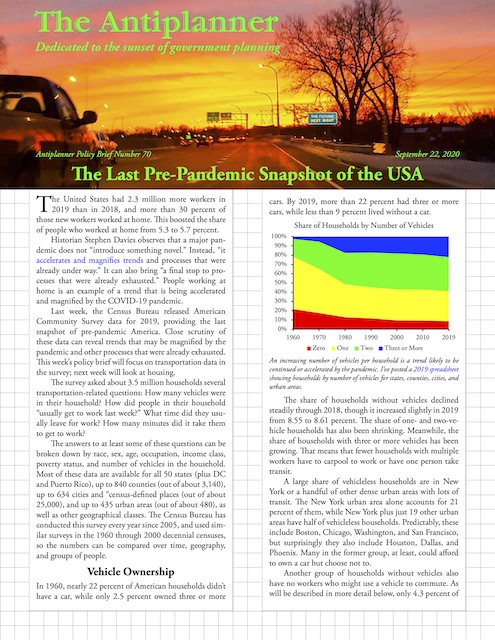

The United States had 2.3 million more workers in 2019 than in 2018, and more than 30 percent of the increase worked at home. This boosted the share of people who worked at home from 5.3 to 5.7 percent.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Historian Stephen Davies observes that a major pandemic does not “introduce something novel.” Instead, “it accelerates and magnifies trends and processes that were already under way.” It can also bring “a final stop to processes that were already exhausted.” People working at home is an example of a trend that is being accelerated and magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Continue reading