While I was in transition from working primarily on public lands issues to working primarily on urban issues, the Forest Service was in transition from focusing primarily on timber to focusing on something else, but it wasn’t quite sure what. Chief Thomas suggested that it should focus on ecosystem management, but ecosystem management doesn’t pay the bills, especially since no one was quite sure what it meant.

My reform proposals called for the federal land agencies to be allowed to charge market prices for all resources and be funded exclusively out of a fixed share of those revenues. I suspected that, on most national forests, this would lead to recreation becoming the most important use, though there would still be room for timber and other uses. The main obstacle to this was that Congress didn’t allow the agencies to charge for most recreation.

That began to change in 1996 when Congress created the Recreation Fee Demonstration program, allowing each of the four main public land agencies (Forest Service, Park Service, BLM, and Fish & Wildlife Service) to begin up to 100 experiments with recreation fees each and letting the agencies keep the revenues. The Park Service approached this with a complete lack of innovation, instead merely increasing entrance fees on 100 parks that were already charging fees and keeping the increased income (the fees that were previously being collected went into the Land & Water Conservation Fund). Continue reading →

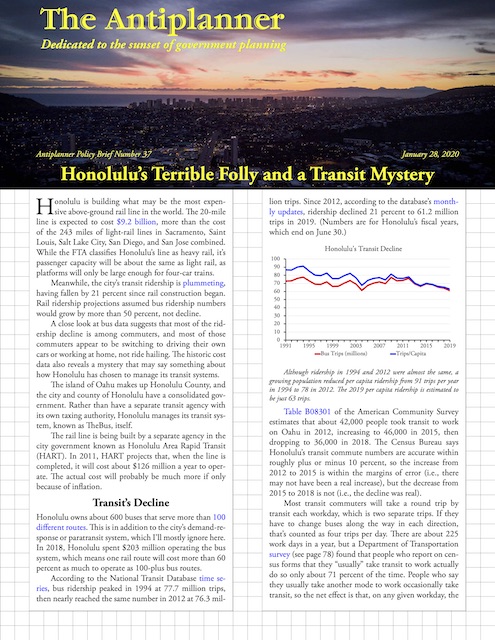

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

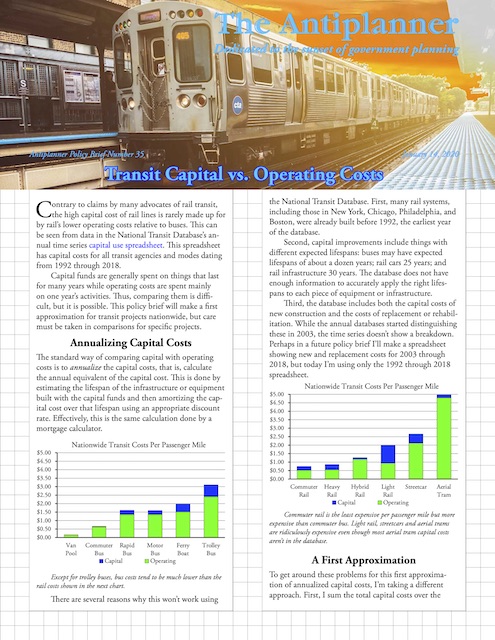

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.