In December, 2004, France opened the Millau Viaduct, which by some measures is the largest bridge in the world. More than a mile-and-a-half long, supported by pylons that are as much as 1,100 feet tall, the bridge carries auto and truck traffic as high as 900 feet above the Tarn valley below, reducing the journey across the valley from many minutes to barely more than 60 seconds.

The bridge cost 394 million euros, well over half a billion dollars in today’s money. What was most interesting to me is that not a penny of public money went into construction (though some was spent on planning). Instead, this was a public-private partnership, meaning the public granted a private company, in this case a construction company called Eiffage, a franchise to build, operate, and collect tolls from users of the bridge. After a certain number of years, in this case 40 to 75 depending on the amount of tolls collected, ownership of the bridge reverts to the public.

I had probably heard of public-private partnerships before, but this was the first concrete example (no pun intended) that I knew about. Never having been to Europe, I decided I should go to France to see it. My friend and colleague, Wendell Cox, was teaching at a French university, and he invited me to join him on a road trip. In addition to Millau, we would visit Halle-Neustadt, the supposed most-sustainable city in the world.

Since first hearing about Halle-Neustadt at the 1999 Sustainable Transportation Conference in Berkeley, I had done more research about urban planning in general and that city in particular. While my university fellowships were helpful in such research, I discovered that, thanks to the Internet, I no longer needed to be near a major university library to do research. Through Abebooks.com and bookfinder.com, I was able to find and purchase a wide variety of books at a modest cost. In fact, I ended up buying hundreds of books about transportation and urban planning, mostly for about $4 to $5 apiece.

(If you aren’t familiar with Abebooks and bookfinder, start any book search with bookfinder, which has Abebooks as one of its sources but also has Amazon and other sources that Abebooks doesn’t have. Bookfinder will identify books by price including shipping. The problem with bookfinder is that the results of a search can’t be saved and used as a link in a blog post such as this one, so I often use Abebooks instead, which usually has some of the lowest-priced books.)

Perhaps most important was Cities of Tomorrow, a history of urban planning by British planner (and former UC Berkeley professor) Peter Hall, who had received a knighthood for his contributions to the Town & Country Planning Association even though he was one of the country’s greatest critics of the Town & Country Planning Act of 1947.

Hall traced modern urban planning back to the late nineteenth century, when people such as Jacob Riis had alerted people to How the Other Half Lives. This 1890 book used photographs to show the terrible living conditions in high-density tenements found in many major cities. Early planners, who Hall called “anarchists,” sought to get working-class people out of these tenements and into the same types of suburbs then being inhabited by middle-class families.

That eventually happened, but it was thanks to Henry Ford, not urban planners. Ford’s moving assembly line made automobiles affordable to working-class families, enabling them to buy cheap land and build cheap homes outside of the big cities. Since moving-assembly lines required lots of land, the jobs moved to the suburbs too.

This led to a backlash, however, which came from two sources. First was the planners themselves, who were appalled by the suburban neighborhoods built by the working class. In books published in Britain before World War II, and echoed by books published in America in the 1950s, planners complained that the suburbs were boring, sterile, and that the people in them didn’t truly appreciate country life. As Hall observed, what really offended the planners were the architectural styles chosen by the working class: instead of building modern, flat-roofed homes, they built neocolonial or other older styles that planners considered to be out of date.

The second backlash came from city governments who saw their tax revenues flee to the suburbs and downtown property owners who saw the value of their land and investments decline.

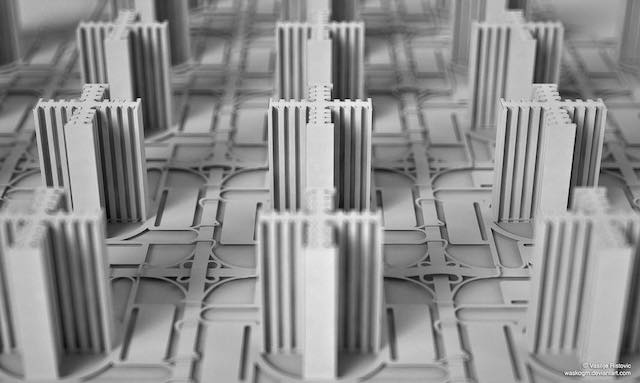

Riding to the rescue was a Swiss architect who called himself Le Corbusier. According to Hall, Corbusier “argued that the evil of the modern city was its density of development and that the remedy, perversely, was to increase that density.” Specially, Corbusier proposed that all new urban development, for housing, retail, offices, and factories, be in high rises surrounded by greenspaces, and that all existing development be replaced by such high rises. He called this the Radiant City.

Model of Radiant City by WaskoGM. Note the highways between each building and cloverleafs at every intersection — Le Corbusier wasn’t trying to curb driving.

The direct counterpoint to Radiant City was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. Writing at about the same time as Corbusier, Wright argued that the automobile, telephone, and electricity had rendered skyscrapers obsolete, and he proposed that families live in low-rise homes on an acre of land each, with the landscape punctuated by a few factories and office buildings connected by a road network. This turned out to be pretty close to most new construction in America after World War II, except that quarter- and half-acre lots were more common than acre lots.

Factories, farms, residences, and offices were equally scattered across the landscape in Wright’s model of Broadacre City. Photo by Austin Jain-Conti.Mayor de Blasio sound a lot like that today. (Not surprisingly, Corbusier himself never lived in a high rise in his entire life.)

Prodded by city governments and downtown property owners, and given cover by planners and other elitists who claimed to be helping the downtrodden masses, governments began building high-rise housing in major cities all over the world after World War II. Some of this was in response to post-war reconstruction needs, particularly in Europe, but much was just due to high rises being an urban planning fad. In 1949, for example, Congress passed a housing act that resulted in the construction of high-rise housing projects in major cities all over the United States under the excuse that they were replacing slums with better housing.

One of those cities was New York, where an architecture critic named Jane Jacobs objected to Corbusian plans to replace her neighborhood, Greenwich Village, with high rises. Her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, argued that urban planners didn’t understand how cities work, which was true, and that she did understand how cities work, which was completely wrong. According to her, Greenwich Village was the ideal that city planners should strive for.

In fact, most of Greenwich Village was made up of the mid-rise tenements that had been the subject of Riis’s How the Other Half Lives. By 1960, thanks to the automobile, most of the residents had moved out and living conditions weren’t as bad as they had been. But apartments were still too small for people to entertain inside, so they did their entertainment on their front porches, which led to the lively streets that Jacobs lauded. The neighborhood still had a lot of immigrants and ethnic groups who hadn’t yet moved to the suburbs, and Jacobs appreciated the bohemian atmosphere that these groups created.

In 1965, urban planners at the University of Moscow who hadn’t gotten the memo from Jane Jacobs wrote a book called The Ideal Communist City (translated into English in 1971 and available as a PDF today because, apparently, copyright laws don’t apply to communists), which took Corbusier’s authoritarianism to its logical extreme. The ideal family, the planners said, was two parents and two children. Since they would spend most of their time in collective work, school, and play areas, they only needed no more than 225 square feet of living area per adult and 50 to 75 per child, or 600 square feet per family divided into a living room/kitchen, bath, and two bedrooms.

The Moscow planners therefore proposed that all new housing in the Soviet Union and its allies be built as 600-square-foot apartments in mid-rises and high-rises. The book admitted that the only reason it supported mid-rises was that the soviets did not yet have the technology to build high rises, but as soon as it did, it urged that all new housing be in high rises. The book justified this using all the same anti-suburban rhetoric used by British and American planners: suburbs were sterile and created congestion while density was somehow more humane and enabled high use of mass transit.

Although I’ve been accused of claiming that The Ideal Communist City somehow influenced American planners, the reverse is true: I think the Moscow writers were influenced by American and western European planners. As I’ve often told audiences, “In associating planners with communists, I’m not trying to impugn the integrity of planners. Instead, I’m impugning the integrity of communists, as communism, in the sense of worker ownership of the means of production, would have worked if they hadn’t turned their economy over to the planners.”

In any case, the next step on our journey through urban planning history is Compact City, a book written by American urban planners and published in 1972. The book argued that forcing cities to be dense would reduce congestion and save energy because people would walk and take transit rather than drive cars. The authors specifically recommended The Ideal Communist City as a “supplementary reading.” The book supported Corbusier’s Radiant City but admitted that Jacobs’ mid-rise city could work just as well. Either way, the planning profession was now set on densification as the remedy to all urban problems.

By 1990, two architects, Peter Calthorpe on the West Coast and Andrés Duany on the East Coast, were leading the urban planning profession away from Radiant City and to Greenwich Village. Calthorpe called his ideas “pedestrian pockets” and Duany called his “neotraditionalism,” but when they got together in Yosemite National Park in 1991 to write the Ahwahnee Principles, they agreed to call their ideas New Urbanism.

New Urbanists vehemently deny that their ideas and goals share anything in common with Corbusier or Halle-Neustadt. In fact, simply substitute “mid” for “high” and they are practically identical, and just about as authoritarian.

One of the arguments against low-density development is that we can’t afford to build the new highways and other infrastructure that will be needed by such auto-oriented development. So the Millau Viaduct, which showed that infrastructure could be built without huge government investment, was equally as interesting as Halle-Neustadt.

Before visiting these sites, however, I decided to indulge myself with some train rides. I flew into Paris and took a TGV train through Lyon to Milan, and then another train to Turin, where I had dinner with Francesco Ramella, a transportation engineer who would speak at the American Dream Coalition’s 2005 conference a few months after my trip.

Interior of one of the Swiss private/tourist trains.

The next morning I took a train to Switzerland, where I had one of the greatest times of my life riding train after train after train. Among others, I rode the Bernina Express, which loops dramatically over itself to gain elevation in the Alps; the Centovalli, which meanders over the Swiss-Italian border; and the Golden Pass line, with its panoramic seats in the front of the locomotive. I was unable to reserve these seats in advance, but when I boarded the conductors told me that no one had reserved them and they allowed me to sit in them for no extra charge.

The drivers sit in a cab above the panoramic seats on a Goldenpass train.

During the most intense day of my trip I rode eleven different trains, both starting and ending in Leissigen, once the summer home of the inventor of Ovaltine that has now been turned into the hostel I stayed in. I would have ridden twelve trains that day but I missed a connection due to rail construction and had to take a bus for one leg. Switzerland, I later learned, has one of the highest density rail networks in the world, and the highest per capita rail ridership of any developed country.

The one-time summer home of the inventor of Ovalmaltine (Ovaltine in the U.S.), now used as a hostel.

Swiss standard-gauge trains are owned by the government, but most fun for me were the narrow-gauge, private trains, which were mostly used by tourists. However, I did take a very brief ride on a double-decked IC 2000 or Elevino train, which had quiet cars, children’s cars, dining and bistro cars, and other intriguing features. The train was divided into first and coach classes, but even the coach seats were very comfortable. It occurred to me that if Amtrak Superliners had been like these cars, I’d still be an Amtrak customer.

The children’s car on an Elevino train.

On returning to Paris, Wendell confronted me with a question: would we rent a plebeian Opal or a luxury BMW for our trip? The Opal, he said, would only be able to go about 125 miles per hour on the autobahn, and he clearly wanted me to go for a BMW, which he said could easily go 150 or so. But, since the difference was $270, and I was paying half the cost, he allowed me to stick with the less-expensive car. (I paid for it in the end when I had him stop on a freeway shoulder so I could take a photo of a TGV train going by. Apparently, in France, shoulders are for emergency use only and I had to pay the ticket we received for the non-emergency stop.)

We first drove south through Lyon to Avignon, one-time home of the popes, where the head of Wendell’s department at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers lived in an ancient stone house, almost a castle. Then we visited the Pont du Gard, a nearly 2,000-year-old Roman aquaduct that was probably not built by a public-private partnership.

We reached the Millau Viaduct the same day, allowing us to compare Roman engineering with modern engineering. After paying the toll to cross the bridge, we drove the old way to see how much longer it took and look for photo spots. My favorite photos were taken from a village called Peyre, which seemed to have been built on the side of a cliff above the Tarn.

We then returned north and passed through Belgium and the Netherlands on our way to Germany. We went out of our way to visit Wuppertal, home of the world’s oldest operating monorail (technically a suspension railway).

Then we went on to Leipzig, home of the largest train station in Europe.

Interior of the Leipzig train station.

Halle is only about 27 miles from Leipzig. The name means “salt” in Greek and the location has been an increasingly industrial center for hundreds of years. Halle-Neustadt was built to be a high-density residential suburb for people who worked in Halle chemical plants and their families.

Mid-rise and high-rise in Halle-Neustadt. Photo by Gerald Knizia.

Conditions in Halle-Neustadt were even worse than reported in the paper written by the University of Stockholm professors in 1999. Built as a model city following the prescriptions of The Ideal Communist City, the government had first constructed mid-rise housing, boosting the new town’s population from zero in 1964 to 35,000 by 1970. At some point it gained the technology for high-rise housing, and by 1989 the population had grown to 96,000.

Partly or entirely abandoned buildings.

German reunification put that growth into reverse. Halle’s chemical factories, some of the most technologically advanced in the soviet empire, turned out to be woefully obsolete by western standards, so they mostly shut down and many workers moved to the former West Germany. Beyond that, many people just didn’t like living in high-density housing, which they derisively call die Platte, meaning the slab. This referred to the concrete slabs separating each floor of the buildings but could also refer to the shapes of the buildings themselves. One paper about these buildings observes that the “appalling monotony” was a function of the authoritarian nature of the governments that built them.

By the time the Stockholm researchers read their paper at the 1999 Berkeley conference, Halle-Neustadt had declined to 65,000 residents. By the time I visited six years later, the population was down to 50,000. In 2015, it bottomed out at 45,000. It’s gained a few hundred residents since then, but that may only be temporary.

Parking lots in Halle-Neustadt, the city built to be without cars.

Many of the residents who were left had purchased cars, and as the Stockholm paper noted, many of these were parked on the grassy lawns that had been built to serve as public parks. Wendell and I visited the metro station where an underground train took people to Halle; trains still trundled through it but hardly anyone got on or off. A restaurant and other businesses that were supposed to serve passengers had shut down. The trams that went at street level were similarly empty.

As a result of the “big giveaway” in which eastern European housing was privatized to its residents after 1990, most of the buildings are cooperatively owned by their residents. But residents can’t afford the maintenance on buildings that are half empty, and they’ve asked the government to demolish many of them. Some have been torn down, but appropriations for housing demolition haven’t kept up with the shrinkage of the city.

Single-family homes near Halle-Neustadt.

Wendell and I didn’t have to look hard to find single-family homes springing up in nearby areas, not to mention hypermarts to serve the residents of those homes. So while some people say they like living in Halle-Neustadt, many apparently prefer lower densities.

On our way back to Paris we passed through Ronchamp, France, and I saw a sign pointing the way to one of le Corbusier’s most famous buildings: Notre-Dame du Haut. Having grown up pouring over modern architecture books, I recognized the image on the sign immediately and we pulled off the highway to look at it.

Le Corbusier’s one decent building.

Wendell grumbled that modern architects should all have been shot, and today I see the flaws in this style, flaws shared by Radiant City and other modern urban planning. However, unlike most of Corbusier’s buildings, which are highly rectangular with large windows, the Ronchamp chapel is full of sweeping curves. While most of Corbusier’s buildings are essentially imposed on the site, this one is, a la Frank Lloyd Wright, inspired by the site, making it one of Corbusier’s few buildings that still seem appealing today. Unfortunately, its tiny windows set into thick concrete walls are an early example of Brutalist architecture, which leaves me cold.

My trip to Europe made me wonder: if I had become an architect, like I first wanted when I was in high school, would I have still ended up working on urban planning issues in the 2000s? And if so, which side would I be on? Even in high school, I could see the difference between Frank Lloyd Wright and Corbusier and was strongly attracted to the former, so I suspect that my preferences would not be much different than they are now.

thanks.

a note on ”

One of the arguments against low-density development is that we can’t afford to build the new highways and other infrastructure that will be needed by such auto-oriented development. So the Millau Viaduct, which showed that infrastructure could be built without huge government investment, was equally as interesting as Halle-Neustadt.

”

This, as you’ve noticed, has lead to another subgroup of Urbanistas who have taken to arguing that while we can pay for it now, it will be impossible to pay for it in the future; that our ability to pay now is just a ruse.

An excellent paper by the Antiplanner. Several comments:

In countries other than the United States the growth of lower density single family housing after the 1910 was not due to private automobiles that were considered luxuries, and much less common than in the US, but first streetcars and then buses. The Book “History of England 1914 to 1945” by A.P. Taylor describes that the advent of streetcars (and presumably then buses) allowed people to move out of the high density slums and into better low density housing. That and the adoption of radios made it possible for people to stay home in an evening. The book states this starts the decline of fraternal organizations as in an evening it was too difficult to get to them and people were listening to the radio anyway.

An interesting legacy of this is that in Britain there are numerous bus museums compared to just three in the US. This may be because many people have nostalgic memories of their lives travelling predominantly by bus. This all began to change in the 1950’s when car ownership expanded dramatically.

According to an elderly relative of mine, an interesting effect of this was “ribbon development.” Developers would build houses on bus routes where the house fronted onto the road and the backed onto countryside. This resulted in roads with bus routes between communities being gradually lined with houses so it began to seem to those traveling on the road that the countryside was disappearing. My relative claimed the impetus for the 1947 Town and Country Planning act was to curb this ribbon development so there would be visible countryside between communities.

This ribbon development may also be why in places where development is along the freeways, like the San Francisco Bay area, residents think the area is fully developed when less than 20% is.

Paul,

Yes, the first major suburbs were “streetcar suburbs,” and Los Angeles was built mainly in that era, which is one reason why it is so much denser than Sunbelt cities built mainly after WWII. But for the most part, only middle-class people (that is, those with college educations who earned livings by thinking rather than physical labor) could afford to live in streetcar suburbs. It wasn’t until the Model T moving assembly line that most working class families could reach the suburbs.

Antiplanner, I agree with you I should have made it clear I was discussing counties outside north America. For example in the UK in 1951 80% of households didn’t have a car see:

https://www.racfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/car-ownership-in-great-britain-leibling-171008-report.pdf

Even then streetcars had been largely eliminated and replaced with buses. The US bypassed the bus stage and went straight to car ownership, with the benefit of much larger houses on larger lots than were possible in countries like the UK. Since then the lot and house size in the UK has been kept down by the difficulty of building houses due to the urban limit lines created by the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. As in the US, when an urban limit line is established then those fortunate enough to have a house don’t want any more houses built in the countryside, and don’t want the urban limit line extended. Many people in the UK complain of housing costs at the same time that they complain of the countryside being built over. They don’t realize these are conflicting positions.

Many advocates of “Smart Growth” higher density walk able communities etc actually live in single family homes surrounded by a garden. Peter Calthorpe certainly does and gets very irritated when asked what his lot and house size is, and how many miles a year he puts on his car.