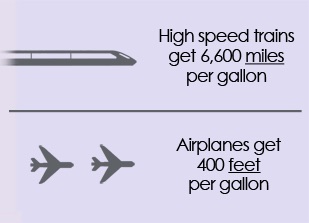

Did you know that a single gallon of fuel is enough to power an entire high-speed train to go from New York to Los Angeles and back? Neither did I, but the U.S. High-Speed Rail Association (US HSR) made this preposterous claim on its web site last week. Someone there apparently figured out that it is ridiculous and took it down, but below is the graphic that accompanied the claim.

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.

Like the claim that one rail line can move as many people as an eight-lane freeway, this claim for energy efficiency is startling enough that we are likely to hear it again as Democrats attempt to spend a few trillion dollars building a high-speed rail system across the country. In preparation for that debate, here are ten reasons why the United States should not build high-speed rail. Continue reading