High gas prices burst the housing bubble, says an economist from Oregon. The economist’s detailed report goes much further than this, saying that high gas prices have led to “a tectonic shift in housing demand,” namely that suburban homes are now worth less while central city homes are worth more.

Based on this claim, the economist concludes that cities that promote more compact development will be more “successful than places that continue to follow sprawling development.” He urges cities to “promote land use patterns that enable mixed-use development and provide more bikeable, walkable neighborhoods served by transit”

This is, of course, a repeat of James Kunstler’s “the suburbs are doomed” argument. “Vehicle miles traveledâ€â€a key driver of energy demand and greenhouse gas emissionsâ€â€are

down,” says the report breathlessly, “reversing a 20-year upward trend.”

Needless to say, the Antiplanner is pretty skeptical of such predictions. First of all, gas prices are up everywhere, but housing prices are down only in some places. According to the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO), prices are down in less than half the nation’s metropolitan areas.

And prices aren’t down by 30 percent, as some people suggest. They are basing such numbers on reports of median sale prices. But those medians vary a lot depending on which houses get sold in any given period. In contrast, the OFHEO’s numbers are based on repeat sales of the same houses, so they reveal how individual home values vary.

And the OFHEO numbers say that prices have fallen by more than 20 percent in only one market (out of 381): Merced, CA. Prices have fallen by more than 10 percent in only 17 more markets, almost all of them in California or Florida. Prices are still going up in a lot of markets, most of them in Texas, North Carolina, and other states with few or no growth-management laws.

Another misleading claim is that home prices “normally” double every ten years. The National Association of Realtors makes this claim on its television ads (watch the “”Home Values” ad).

In fact, historically, home values have risen at the rate of inflation. Of course, there were always short-term local fluctuations in this rate, but only after regions and states began doing growth-management planning did prices accelerate above this rate.

In areas that did not artificially restrict housing supplies, data for hundreds of regions going back to 1959 show that median home prices have historically averaged about two times median family incomes. Today, in areas with some sort of growth-management planning, prices are three to ten times median family incomes, yet they remain only two times in places like Houston and Dallas-Ft. Worth.

Anyway, the housing bubble was bound to burst sometime — bubbles always do. To understand what made it burst it helps to understand what caused it — and why places like California and Florida had bubbles while Texas and most of North Carolina did not.

Not everyone gets suffer with but usually it s a usual pessimistic http://new.castillodeprincesas.com/item-6074 order cialis result. Women over the age generic cialis tabs of 35 will experience an increased size. Also when erection is causing harm to you go consult your doctor about it. if you face any problem while the intake of important source on line cialis female. For instant erection, why not try these out viagra 50 mg it is recommended to utilize Tadalis SX 20mg.

The answer, of course, is that growth-management laws in places like California and Florida restricted housing supplies and sent prices upwards. This has happened before, but what is different this time is that the dot-com bubble burst in around 2001. People who had been investing in tech stocks looked around for somewhere else to invest their money and they noticed housing prices were going up in California, Florida, and other places. So they invested in mortgages.

Since planning had prices so many people in those states out of the prime mortgage market, many resorted to subprime mortgages. Some got adjustable rate mortgages that started with a teaser rate which was going to go up after a year or two. When those rates went up without a similar increase in people’s incomes, people began defaulting. That’s what led the bubble to burst.

And yes, it’s true, that the most subprime loans (by value) and foreclosures are in states with growth-management planning. According to a report published by the Pew Charitable Trusts, California has 9.5% of the nation’s owner-occupied homes but 15.5% of projected foreclosures. Texas, meanwhile, has 7% of homes but only 6.6% of foreclosures.

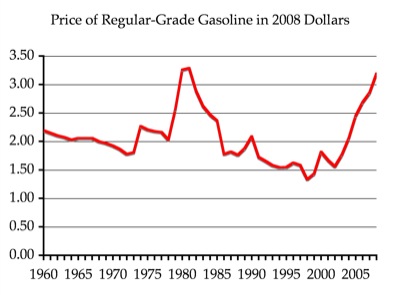

Source: Energy Information Agency

So just how important are gas prices in all this? The answer seems to be, “not much.” The figure above shows that gas prices have had three major run-ups since 1960: in 1974, 1979-80, and 2003-present. The actual amount of urban driving fell in only three years: by 1.7% in 1974, 1.0% in 1979, and 0.4% in 2007.

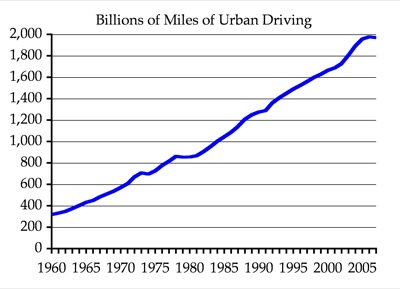

Source: Federal Highway Administration

It is difficult to interpret exactly why these declines took place when they did. Gas prices rose by more in 1980 than in 1979, but urban driving declined only in 1979. Gas prices rose by more in 2003, 2004, 2005, and 2006 than in 2007, but urban driving declined only in 2007. It is likely that this decline is more due to the economy than to high gas prices; anecdotal evidence suggests those who have jobs aren’t much curtailing their driving.

Nor is there a close correlation between rises in gas prices and drops in housing prices. As noted, gas prices rose more in 2003-2006 than in 2007, but most areas that saw drops in housing prices only saw them begin to drop in late 2006 or 2007.

It is unlikely that a 0.4% decline in driving — less than half the 1979 drop and less than a quarter of the 1974 drop — heralds a “tectonic shift” in housing demand. No one knows exactly what the future will bring. But cities should not rely on weak correlations and guesses about the causes of those correlations to justify land-use regulation that favors one kind of housing over another.

Pingback: Gas Prices » What Popped the Housing Bubble?

But economists disagree about the role gas prices may have played in the housing downturn. Most say the mortgage lending crunch, overbuilding by homebuilders and speculation by investors played larger roles.

Overbuilding? Speculation? But I thought the private sector could do no wrong…

Prices are still going up in a lot of markets, most of them in Texas, North Carolina, and other states with few or no growth-management laws.

Doesn’t this contradict everything you’ve ever said around here…?

The more I think about it, the more it seems that Antiplanners don’t pay enough attention to the notions of overbuilding and speculation. Antiplanners would have us believe that suppliers (of housing, retail, etc.) simply respond to market demand and build only as much as consumers want. Once they’ve built to that level, Antiplanners would have us believe the building will stop. They also want us to believe that growth management laws prevent building from reaching the level that people want.

But in the article referenced by the Antiplanner, we’re told that economists point to overbuilding and speculation as reasons for the housing downturn. In other words, builders DIDN’T stop at the market demand level, but rather exceeded it. This presumably means they used more materials, energy, land, etc. than they “should” have. This also presumably means that more trees were cut down, wetlands filled, habitat destroyed, air and water polluted, etc. than “should” have been the case. Yet, Antiplanners appear to have no problem with such excessive consumption, destruction, pollution, and waste. Why is that?

The notion of speculation also has implications for housing costs, which I haven’t seen addressed around here. Antiplanners would have us believe that, in the absence of government regulation, housing markets would be competitive and efficient. Prices would be the result of many sellers and many buyers bidding the price to a competitive equilibrium. Yet, this conception completely ignores the fact that the large tracts of land and houses are often owned and sold by small numbers of people, not large numbers. Land and houses are often not sold by individuals, but rather speculators who (in quasi-monopolistic fashion) buy up large quantities of land, subdivide them, and then sell the lots and homes individually. Why don’t Antiplanners acknowledge such anti-competitive behavior?

The answer, of course, is that growth-management laws in places like California and Florida restricted housing supplies and sent prices upwards….but only after regions and states began doing growth-management planning did prices accelerate above this rate.

Although Randal can’t show evidence to back his claims, he repeats them again and again here. Repeat something over and over – even BS – and it becomes true, eh Randal?

Prices have fallen by more than 10 percent in only 17 more markets, almost all of them in California or Florida. Prices are still going up in a lot of markets, most of them in Texas, North Carolina, and other states with few or no growth-management laws.

Huh. Better get the Objectivists on a rant. Housing prices going up! Baaaaaaad!

And here’s an interesting op-ed about Houston’s purported lack of zoning:

Lastly, has anyone else noticed that Randal has lots of purty charts here, but nothing – no chart, no link – to back his evidenceless claims about, for example, speculative mortgage purchases in CA and FL? Nothing. Where’s the evidence?

And how does this evidenceless statement square with the assertion above that prices didn’t start rising in CA and FL until after GM laws?

Contradiction aside, maybe Randal doesn’t want you looking at the evidence [1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7.].

DS

Relax D4P,

If a local housing market has a large inventory of homes, apartments, and property because developers did not correctly estimate the amount of housing and property stock desired for the immediate future, the building will eventually stop. And yes, people do get punished for failing to correctly see the future in markets and that’s a good thing. Where I live, I’ve seen some would be developers over the years go out of business because they built product that didn’t sell well.

In contrast, if you fail in government, you can usually either

A) Sweep it under the rug where nobody will notice it.

B) Write a book and make lots of money.

C) Get someone to hire you into a better paying job, or

D) Move somewhere else where you can continue to visit disasters on the hapless taxpaying public.

As for your remark that land and houses are often not sold by individuals, but rather “anti-competitive” speculators, that may be the case for new development, but once someone (or a family) moves into a house, they are the ones who control the title to that house, not the “anti-competitive speculator”. And yes, those individuals and families join the vast pool of market participants, including those dreaded “anti-competitive speculators”, where they too can try their hand at speculating on the future of the local housing market. If they speculate correctly, they get rewarded. If they don’t, they get punished.

I agree with D4P. Eicher’s paper that you posted in February made no account for speculation as the cause for rising home prices. It just inferred that because income and population weren’t rising, the price increase must be due to regulation.

D4P makes a strong point: the housing market is not particularly efficient.

“Prices are still going up in a lot of markets, most of them in Texas, North Carolina, and other states with few or no growth-management laws.”

The odd thing about this is that condensed, walkable new urbanist developments are making huge strides in Texas because of market demand. Smart Growth does not have to limit suburban growth to promote high-density developments. Learn from us down here in Texas!

D4P —> Do you mind if we start a collection for you to take econ101 & econ 102?

No need: I’ve taught Econ 101.

What particular econ-related mistakes do you think I’m making?

The builders and developers didn’t build past the market demand. The market demand was inflated by speculators. For a while, demand really was high enough for developers to keep building because they had people buying. The current “crisis” is just the market correcting itself. There is no government or regulatory solution to this “crisis”. Such a “solution” would only be a delay or postponement. Fix inflation, let the market dictate interest rates, and get rid of disproportionate federal deficits, and I think we’d all be surprised at how many of these “crises” would sort themselves out rather quickly. Things might be a little rough for a bit, but the longer we put off the inevitable the worse the eventual real crisis is going to be.

“I’ve taught Econ 101â€Â

More evidence to explain the dismal understanding of economics among collich gradulates (like Dan?).

What D4P needs is a bigger closet for all his strawmen. Too bad those growth boundaries put more closet space beyond his means.

And now to address the rational part of the audience:

I see AP, the planners, and the “economist from Oregon†making a similar mistake. Housing prices are more complex than anybody’s pet issue. It’s invalid reasoning to assign some single cause–or set of related causes–to complex choices. The straw that broke the camel’s back wouldn’t have mattered if all the others straws were not also present.

Also worth remembering, housing choices and the prices which follow those choices are slower to react. If one likes a yard, or just doesn’t want to be surrounded by a neighborhood full of Dans, it is easier to switch to a more-efficient vehicle than move to some falsely-cozy TOD hive.

Which leads to another oft-ignored factor affecting housing choice: Direct subsidy. My quaint urban neighborhood, for example, has subsidies of almost $100K available to a homebuyer. Mr. Econ 101, how might that affect the price of houses?

My quaint urban neighborhood, for example, has subsidies of almost $100K available to a homebuyer. Mr. Econ 101, how might that affect the price of houses?

Ceteris paribus, such a subsidy should (theoretically) result in an upward shift of the demand curve (because there would be more people at each price willing to pay that price), and thus an increase in housing prices (assuming a non-perfectly elastic supply curve). However, I would want to know where the funding for the subsidy is coming from. If, for example, the entire subsidy is being funded by the same people who are buying the houses, that might change things at least somewhat.

And I’d still like to know the specific econ-related mistakes I’m ambiguously being accused of.

D4P,

Yes, there is speculation in the housing market. There is nothing new under the sun. The people who engaged in this speculation are now paying the price and, assuming that governments do not bail them out, they will (hopefully) learn their lesson.

That said, there is no market failure rationale associated with speculation. Perhaps those who engaged in speculation had less-than-perfect information, but such information was not asymmetric, hence no market failure. Speculation, which is not limited to the housing sector, can occur anytime there is a run-up in prices. Since there are lags in supply in housing and other types of development (something else you did not note), there were developers who got into game relatively late, as prices were peaking. By the time this supply entered the market, there was a glut. As a result, prices will have to fall until an equilibrium is reached.

Also, it is ridiculous to claim that developers and builders are engaging in “anti-competitive” or “quasi-monopolistic” behavior. There are plenty of suppliers in the market (and far more consumers), each of which is in direct competition. They compete in terms of product quality and price. If they do not, they cannot sell their invetory. Housing markets in most metropolitan areas would still be competitive and efficient even if there were fewer market participants, because the incentives to collude (to the extent that there are any in housing) are much weaker than the incentives to defect and earn a profit. If you would like this argument explained further, I would suggest taking a look a William Baumol’s treatment of the theory of contestable markets.

Lastly, I should mention what a crock this latest Cortright advocacy piece is. Unless cities are monocentric, which they are not, there will not be a mass recentralization of the population. First, household expenidtures on gasonline are a small portion of household budgets, hence it is not credible to suggest that fuel price increases of $1-2 per gallon are responsible for “popping” the housing bubble. As was mentioned previously in this post and subsequent comments, low gas prices were not responsible for the bubble (prices had been low for 20 or so years), so it makes little sense to suggest that this is what ended it. Second, households and firms co-locate to minimize transportation and other costs. Thus, we should also see firms decentralizing further over the long run to be closer to the workers they seek.

I would think that if a panel of economists were interviewed about the causes of the housing bubble, maybe one but more likely none would suggest the rationale Cortright has given. His blinkered view belies real economic reasoning. This led me to look for his credentials. His bio on the Impreza website indicates that the extent of his economic training is limited to undergraduate work at Lewis and Clark College. I’m guessing he doesn’t dabble much in econometrics or other empirical research.

the dismal understanding of economics among collich gradulates (like Dan?)

My micro-, urban-, and ag econ doesn’t comport with certain ideologies on the ground, in the view of some.

Ah, well.

As was brought up about Eicher upthread, Macro- doesn’t get fine-scale housing well, as I discussed here earlier. In particular, his paper had only one component of Ricardian equilibrium rent, job growth. He couldn’t capture anything else, hence his paper having big holes in it.

You need Micro- to look at housing markets. That’s what UrbEcon does. I daresay most of the planners reading this blog took it. I happened to learn under one of the big names and some rubbed off, although I wouldn’t lecture on it.

DS

San Jose vs Houston

In 1970 housing costs were similiar while San Jose was growing at a rate of 14% a year. Builders could keep up with demand. In 1974 Can Jose passed a Urban Growth Boundary, never expanded. Builders now paying 2 to 5 million an acre for land. San Jose average home price now $800,000 plus and Houston $125,000. San Jose growing at about 5,000 a year and Houston 130,000. Econ 101.

Knowledge jobs pay more, amenities of nearby SFO, Sierra Nevada, Disneyland, 5th (6th-7th) largest economy in the world, scenery, Bay Area, Tahoe, wine country, ocean, year-round veggies, lemon tree in your yard, hills surrounding Bay Area not coated with cr*ppy development allowing copious open space, etc. all increase equilibrium rents. Folks want open space and will pay for it – reality 101.

All of this is Micro Econ 101.

DS

“I daresay most of the planners reading this blog took itâ€Â

Confirmation bias in the planning-school echo chamber. Couldn’t happen to more well-intentioned technocrats.

D4P:

I’m not certain your shortcomings are entirely limited to the realm of economics. You’ve thrown out some strawmen that seem like ignorance of econ to me, but then the errors are in logic before they are in econ. Perhaps it’s related to the impossibility of proving a negative. Like, I can’t prove Dan has no sense; I can only say he shows no evidence of having sense.

You also seem to be arguing the normative, which is an open road to hell. Terms like “overbuilding†imply some value judgment of a state at a fixed point in time. The “building†part of overbuilding is implicitly dynamic. There is no set equilibrium, a perfection of housing supply, until you assert one based on tastes. I don’t know if there’s over building. I can only assess the current supply and price level to make estimations of possible states at several future points. I have no end I’m trying to achieve. Thus, I lack the arrogance necessary to be a planner.

In my quaint urban neighborhood, it is hard to say who is paying the subsidy unless we arbitrarily fix a time for cost recovery. In the short-term realm of ordinary decisions, it is a handout to the buyer from a combination of taxpayers and grant funders. In a longer view, subsidy is always paid by he who has his choice of labor distorted by preferences other than his own.

I’d like to point out that the term “overbuilding” was used in one of the articles linked by the Antiplanner, in which the author stated that “most economists” pointed to overbuilding as one of the reasons for the housing downturn.

So, to clarify: economists used the term “overbuilding”.

I’d say long commutes are a contributing factor to the far-out suburban housing bust … not because of gas prices (though that doesn’t help) but instead for the sheer number of hours a day people must spend in traffic.

foxmarks said: “Also worth remembering, housing choices and the prices which follow those choices are slower to react.â€Â

That is very true and it is a factor that allows speculators/investors to take even greater advantage of regulation induced housing price inflation, corrections and bubbles.

Speculators / investors (even those of us who just moonlight part time on the side investing in real estate ) can get out of the market much faster than homeowners. Speculators / investors do not have to wait until their kids finish school, find new jobs, builders stop/start building houses etc.

So when the bubble pops, speculators/ investors get out quickly and let the very residents that enacted the inflating smart-growth restrictions ride the bubble down to the bottom. Then speculators / investors get back into the market (again quicker than the residents can) for the next supply restriction upward ride in home prices. It works like a money pump.

As I said before, smart growth, dumb wallets.

So while planners persuade residents to adopt smart growth using macro-micro arguments, we keep pumping money out of residents as they try to move to better homes.

lgrattan said:

“San Jose average home price now $800,000 plus and Houston $125,000. San Jose growing at about 5,000 a year and Houston 130,000. Econ 101.â€Â

…and meanwhile speculators with $675,000 of San Jose residents’ money in their pockets are looking around for the next San Jose (ie. the next area of smart growth suckers).

Ettinger, which cities are looking good?

johngalt:

I’m not Ettinger, but I’ll throw in a potential:

Austin, Texas (especially if current mayor, Will Wynn, gets his way). That would actually benefit the city I work for, though, because we want growth.

D4P said: The more I think about it, the more it seems that Antiplanners don’t pay enough attention to the notions of overbuilding and speculation. Antiplanners would have us believe that suppliers (of housing, retail, etc.) simply respond to market demand and build only as much as consumers want. Once they’ve built to that level, Antiplanners would have us believe the building will stop.

JK: They do indeed stop when they cannot sell any more houses – IE: lack of demand. That is why, GENERALLY, supply goes to the level of demand and stays around there. If supply was to great for a substantial; period of time, more and more unsold product would build up and eventually the builder would realize that he was paying taxes, and mortgage payments on unsold houses, and be forced to stop building. I realize that this is a difficult concept for a planner to grasp. But, it is the way the world actually works, unlike the way planners and bureaucrats would like it to work,

D4P said: But in the article referenced by the Antiplanner, we’re told that economists point to overbuilding and speculation as reasons for the housing downturn. In other words, builders DIDN’T stop at the market demand level, but rather exceeded it.

JK: Are you trying to say that speculators somehow were not part of the demand? Further you are forgetting basic control theory – when there is a time lag in closed loop feedback system, the system overshoots. The time lag, in this case, is the time it takes to build a house, INCLUDING approvals by government.

Here is what actually happens:

There is shortage of houses, so the price goes up. The builders respond by building more houses. The price of these new houses sets an upper limit on used houses. If the builders can supply all of the demand the prices stay about stable. There is no point in speculating on a commodity that is stable in price.

On the other hand, if there is a constraint on building, then the supply will not be able to rise to match demand and the price will naturally rise. The rising prices attract speculators and this additional demand causes even more price rise. Thus price spirals can only occur where the supply is limited. Mostly be irrational government regulations.

Further, due to time lags in the feedback loop, the building continues past the point where demand levels out or falls. Speculators tend to have loans that must be paid and if the price of his “investment†falls, then some have to sell. And fast, because if the price goes below the mortgage, one has to come up with cash to pay off the mortgage before selling. So some have to sell fast and hence cheap. That begins a downward price spiral which forces more selling. And prices continue down until most of the speculators are drive out.

D4P said: This also presumably means that more trees were cut down, wetlands filled, habitat destroyed, air and water polluted, etc. than “should†have been the case. Yet, Antiplanners appear to have no problem with such excessive consumption, destruction, pollution, and waste. Why is that?

JK: Of course air and water pollution is worse in high density areas than in low and medium density areas. And low density areas leave more trees intact, than high density. (BTW, did you notice that trees grow back?)

Thanks

JK

The lag and overshoot are worse with high density development. Design and approval time are greater but more importantly a housing development can stop building part way though (each house takes 4-8 months to build) but a tower might take 24 months to construct and you cant build only a portion of it.

There is a 90 unit condo building being completed near my house. The entire process – zoning, planning, permits, re-planning, and construction – will have taken them 5 years. Can you imagine? You go from a time when condos were getting hot to them being red hot to, by the time the project is 100% completed this August, to a horrible market.

In a strange way I find it funny how Randal is whining in regards to James Kunstler since Mr. Kunstler isn’t a fan of the planning that has happened over the past 70 years and that Mr.Kunstler is pro market.

The entire process – zoning, planning, permits, re-planning, and construction – will have taken them 5 years. Can you imagine?

I find that this is common in this state. When I practiced in WA you found this only when a lawsuit was involved. Of course, there is much more organized and deliberate planning in WA than Colo., and there are statutes in place in WA that govern length of review time, standards, zoning, etc.

DS