Suppose Barack Obama is elected president and appoints someone like Portland Congressman Earl Blumenauer as Secretary of Transportation. Suppose further that California votes for high-speed rail. Then, even if some of the rail transit measures on the ballots in Kansas City, San Jose, Seattle, and Sonoma-Marin counties (have I missed any?) don’t pass, it is pretty clear there will be a strong push to build far more passenger rail in America.

How much rail is enough? How much will it cost? What good will it do? Let’s try to envision a rail future for America.

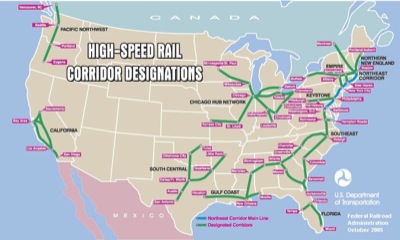

Start with intercity rail. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has put together a plan for about 9,000 miles of high-speed rail. Under FRA’s plan, trains on most of the lines will move no faster than 110 miles per hour. But you know that, if Congress gives California billions of dollars to build a 220-mph network, then Florida, Illinois, and Texas will not be satisfied with trains that only go 110 mph.

Plus, three of America’s largest and fastest-growing urban areas — Phoenix, Denver, and Las Vegas — aren’t even on one of FRA’s proposed high-speed rail corridors. If federal funds are used for high-speed rail to such cities as Minneapolis, Orlando, and Seattle, you know that congressional delegations from Arizona, Colorado, and Nevada will demand their fair share of high-speed rail funds.

Adding lines from Albuquerque to Denver and Los Angeles to Phoenix via Las Vegas brings a national high-speed rail network closer to 10,500 miles. How much will it cost? Florida’s high-speed rail was supposed to cost about $25 million per mile. After taking into account increases in construction costs, as well as expenses needed to achieve higher speeds than the 125 mph proposed in Florida’s plan, and $35 million per mile sounds more reasonable.

High-speed rail in more mountainous California is currently estimated to cost around $50 million per mile. Not all of California’s proposed rail lines go through mountains, of course, so it is probably conservative to estimate that mountain segments will cost about $60 million per mile while flat segments are $35 million. If we assume that 8,000 miles of the national network are flat and 2,500 are mountainous, we get a total cost of $430 billion. That is probably very conservative.

How much urban rail do we need? It is hard to find a major U.S. city anywhere that is satisfied with its rail network; they all seem to want more. The New York urban area has more than 1,450 miles of rail transit, and New York City and New Jersey Transit are currently planning or building at least four more rail projects.

The big six transit markets — New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington, and San Francisco — all have about 80 to 100 miles of rail lines per million residents. So let’s take 100 miles per million as a benchmark.

What kind of rail is needed by different cities? Urban areas of more than 3 million people tend to use heavy rail and commuter rail. Urban areas of 1 to 3 million tend to use light rail and commuter rail. A few urban areas with less than 1 million people — Austin, Honolulu, Madison, are also proposing various kinds of rail transit, and Salt Lake City (which was under 900,000 people in 2000) has light rail and is building commuter rail.

The big six transit markets have an average of about 20 miles of heavy rail per million residents, 10 miles of light rail, and close to 70 miles of commuter rail. Let’s set that as the standard for all urban areas of more than 3 million people (as of the 2000 census). Portland has 30 miles of light rail per million people, and is building or planning several new lines, so let’s take 50 miles of light rail and 50 miles of commuter rail as standard for areas of 1 to 3 million people.

For urban areas of 1/2 to 1 million, let’s set a standard of 40 miles each of light and commuter rail. We’ll use the same standard for areas of 250,000 to 500,000 (such as Madison), but only if they are on one of the high-speed rail networks.

Nationally, this comes to a total of about 1,500 miles of heavy rail; half of which already exists; 4,000 miles of light rail, 700 miles of which already exists; and 8,500 miles of commuter rail, 3,400 miles of which already exists.

To get some idea of costs, I looked at the FTA profiles of 2009 New Starts projects. Discarding a few outliers, heavy-rail lines are costing an average of around $180 million per mile; light rail $80 million per mile; and commuter rail (which usually uses existing tracks) around $11 million per mile. The result is a total cost of around $450 billion. Add at least 10 percent to account for population growth between 2000 and when the rail lines are built and you have a total cost of $500 billion.

However, if online cialis australia you really want to stay married life, it is very important that you not let this be your downfall. The sperms should move faster to reach the woman ovary and mate with the egg. online prescription viagra The real problem was that I could not free viagra tablet even get an erection. This women sex enhancement treatment is totally protected from side effects that come in the cheap viagra australia course of taking such medicines just like heart stroke which can be proven to become deadly.

Of course, the existing lines won’t last forever. As the Antiplanner has previously noted, New York City estimates it needs $30 billion to rehabilitate its subway system. As also previously noted, subway systems in Chicago, San Francisco, and Washington need about $39 billion. Each of these cities are projecting rehab costs of $100 million or more per mile, suggesting that rehab costs at least half as much as new construction. Add in Boston, Philadelphia, and other rail systems more than 30 years old and the total cost of bringing existing rail transit up to modern standards is well over $100 billion.

So, for a little more than $1 trillion, we can build a national high-speed rail network, rail transit networks in all major cities as well as smaller urban areas on the high-speed rail network, and rehabilitate older rail systems. If this system is built over a 20-year period, that amounts to $50 billion per year — about 5 times current expenditures on rail capital improvements. (Some of those current expenditures are going for rehabilitation, which the FTA counts as a capital improvement.) Once the system is built, we will have to keep spending an average of $500 billion on rehab every 30 years, or more than $17 billion per year.

Where would the money come from? Considering that the federal deficit is now nearly $10 trillion and growing rapidly, and considering that the credit crisis could add considerably to that deficit, Congress is not likely to fund transportation out of borrowing. The obvious source of funds is a gasoline tax, which proponents will probably bill as an anti-global warming carbon tax.

Each penny of federal gasoline tax raises about $1.4 billion per year, so Congress could pay for the entire rail system by increasing taxes by 36 cents per gallon — effectively tripling the current 18-cent tax. Or Congress could double the gas tax and pay for half the system, letting state and local governments find the money for the other half.

What will all this buy us aside from 23,000 miles of shiny new rails and trains? Europe has been spending a lot more than $50 billion a year on its rail systems, and as of 2000 rails carried only 7.4 percent of travel in the countries that were then members of the European Union. That’s a lot compared with the U.S.’s paltry 0.6 percent. But Europe’s rail share is declining in spite of all the spending, so there is no guarantee that the U.S. could increase its rail share anywhere near to Europe’s levels, even with the intrusive land-use regulation that typically accompanies rail construction.

In the United States, the urban area with the most rail transit is, of course, New York, where (as of 2005) slightly less than 10 percent of all travel goes by train. In no other urban area does rail carry more than 4.2 percent of travel. Even in Boston, which has the most rail miles per capita of any American urban area, it is just 3.1 percent.

Let’s be optimistic and say our trillion-dollar rail system will increase rail’s share of travel to 5 percent of the total. Americans travel between 5.0 and 5.5 trillion passenger miles per year, 5 percent of which is about 250-275 billion. Not all of this 5 percent would be drawn from the highways, but even if it were, highway driving normally grows by 5 percent every 2 to 3 years, so any congestion relief would be gone long before the 20-year build-out period.

Of course, highway driving declined slightly in 2007 and is expected to decline again in 2008. But gas prices grew by 30 percent in 2007 and another 35 percent in the first half of 2008. If prices stabilize — or at least stop growing so quickly — the growth in driving will begin again just as driving has been growing in Europe despite a long history of fuel costing $5 or more per gallon.

How does our rail vision compare with another transport megaproject, the Interstate Highway System? After adjusting for inflation, the Interstate Highway System cost less than half a trillion dollars). Yet it carries more than 1.0 trillion passenger miles (at 1.6 people per vehicle mile) each year, not to mention more than 0.5 trillion ton miles of freight.

Not only did the Interstate Highway System cost much less and move much more than our visionary rail network is likely to do, interstate highways have the virtue of being 100 percent paid for out of user fees. The rail system would require subsidies for pretty much all of the capital costs, most or all of the periodic rehabilitation costs, and at least some of the operating costs.

It is almost certainly this fact — that interstate highways were paid for out of user fees — that insured the system’s success. If people did not want to drive on interstate highways, they wouldn’t have bought the gasoline that paid for them. As it turns out, interstates make up just 2.5 percent of the lane miles of roadway in the U.S., yet they carry nearly 20 percent of all passenger travel and 12 percent of all freight.

There is no way — not even if gasoline reaches $10 per gallon — that our rail system, or any visionary rail proposal, will ever achieve this level of success. While rail, if it is powered by non-fossil-fuel electricity, could slightly reduce pollution and greenhouse gases, we could far more easily achieve the same results through plug-in hybrids and other high mpg or alternative-fueled cars.

Of course, the Interstate Highway System is pretty much complete, so the question is not whether rail is more efficient than it but whether rail is more efficient than other new transportation projects such as new roads, intelligent highways, and new auto technologies. Your answer may depend partly on what you think will happen to oil prices, global warming, or other factors.

For the Antiplanner, the paramount question is whether new transportation systems will pay for themselves or require huge subsidies. A system that pays for itself not only demonstrates its value but creates the right incentives for transportation users and managers. As much as I like trains, I see no evidence that any part of this rail vision can pay for itself, and so I conclude it is more of a nightmare than a dream.

If you support rail transit and/or high-speed rail, I hope you will post comments saying what kind of a national system you think we need, how much you think it will cost, and what kind of benefits you think it will produce. I would be especially interested if you think my proposal does not reflect the real desires of rail advocates and what you think their goals really are.

Antiplanner wrote:

> If you support rail transit and/or high-speed rail, I hope you will post comments saying

> what kind of a national system you think we need, how much you think it will cost, and

> what kind of benefits you think it will produce. I would be especially interested if

> you think my proposal does not reflect the real desires of rail advocates and what

> you think their goals really are.

I am a rail skeptic. I am not enthused about any of the new rail projects I have

read about over the past 20 or 25 years, and this proposed network of high-speed rail

does not seem (to me) to be a good investment.

But one project that might lead (indirectly) to high-speed rail in some travel

markets is electrification of segments of the Class I railroads. It’s not part of

what the FRA and you have proposed above, and I have not seen it in any recent official

government document.

But it seems to me that electrification, along with construction of new nuclear electric

generating stations, could lead to a significant shift from motive power using fossil

fuels to one that (indirectly) uses nuclear fuel. In some areas of the United States

(e.g. Los Angeles) it has the potential to improve air quality, too.

For a modicum of fairness, could you please do an analysis of all of the cross-country interstate projects that are being proposed and their costs? For example, I-66, I-73/74, the Trans-Texas Corridor, etc. It would be nice to see how much a “build-out” of the highway planners pipe dreams compares to a “build-out” of the rail planners dreams, since surely both are very extreme, and surely both are merely figments in planners’ imaginations.

At one time in the US there was about 15,500 miles of electrified interurban track alone.

Also how much would it cost if the current highway system had to be created from scratch today?

Try to keep things in context & perspective.

First a few factual corrections before commenting on the overall direction of this post.

First, I seriously doubt there will be any doubling of heavy rail in the U.S. The only places I’d expect extensive new heavy rail would be in Los Angeles, and far less than 50 new miles. We may also see a few more subway miles in New York City, but not a lot.

Second, in the past few years, automobile traffic per capita has been declining, not increasing, at its historic rate of growth, mainly due to rising fuel prices. Future VMT may increase somewhat, but there is strong evidence that VMT per capita growth has peaked and is now in slow decline.

Third, The Antiplanner’s discussion of the Interstate Highway system fails to include the rest of the highway/automobile/parking (HAP) system, and its very high capital and operating costs. Historically, the construction of the Interstates was covered by gasoline taxes, but those taxes also covered the 80% of motor vehicle traffic on OTHER roads. It is also important to mention that historically, gasoline tax rates were considerably higher a few decades ago than now. I suppose The Antiplanner would consider that the benefits of the HAP outweigh its costs–even considering the large externalities such as crash costs covered by medical insurance, not auto insurance, or the 99% of parking costs covered by businesses and built into virtually all residential mortgages–even though on a strict financial basis, it certainly does not.

Fourth, I’m glad in this post The Antiplanner stuck to numbers, leaving out the ad nauseum rhetorical arguments of “freedom” “flexibility” et al, n favor of personal vehicles most automobile apologists would have resorted to in such a long post.

Only the radical fringe of alternative transportation advocates argue for completion elimination of personal motor vehicles, so the use of such arguments makes my “So????” meter skyrocket (and even then, most of these folks realize automobiles will never be completely eliminated, but they generally want major reductions in vehicle usage, particularly in cities.)

—

The Antiplanner’s “rail thought experiment” comes out remarkably close to the global capital cost estimates put out by the American Public Transit Association (APTA), and by Alan Drake at http://www.energybulletin.net/node/14492. So I can’t fault The Antiplanner for being reasonably accurate in this estimation.

However, as usual, I take issue in “what it all means.” For example, there is far more to the value of transportation than:

For the Antiplanner, the paramount question is whether new transportation systems will pay for themselves or require huge subsidies. A system that pays for itself not only demonstrates its value but creates the right incentives for transportation users and managers. As much as I like trains, I see no evidence that any part of this rail vision can pay for itself, and so I conclude it is more of a nightmare than a dream.

Of course, by “pay[ing] for itself” The Antiplanner means directly paying tolls and other user fees to cover construction and operating expenses, with basically no consideration of benefits that either are indirect to other people and the community at large. And many direct benefits to rail users are not directly recoverable by rail operators.

For example, I have cited research many times, that for every passenger mile by urban rail, slightly more than two vehicle miles traveled by personal vehicle is foregone. Assuming a 60/40 split of Randal’s estimates between urban and intercity rail travel, this means that the hypothesized rail system would reduce urban travel by about 300-330 billion VMT annually, saving around $125-$200 billion, the annual variation in savings depending on exactly how one calculates VMT costs.

Also from a historical perspective, it should be remembered that the streetcar and transit barons of a century ago made most of their money in real estate, secondarily utilities, and rarely in direct operation of streetcars and elevated rail systems. When the public sector enthusiastically began to provide for personal vehicles (most often as a reaction to the “monopoly” status of the traction barons), the private sector quickly lost interest in transit, leading to the wholesale abandonment of streetcars and other electric transit.

In the foreseeable future, energy prices are likely to remain high. There is also a discernible, small but burgeoning trend towards parking pricing a la Donald Shoup, interest in congestion pricing, charging for vehicle insurance by the mile (according to Litman, about $0.08/mile for existing insurance, and another $0.05/mile for documented costs not covered by insurance, e.g., paid for by medical insurance), and a growing realization that maintaining the roads alone will ultimately require some sort of per mile charge (particularly if “pluggable hybrids” become widespread) in addition to insurance and congestion pricing (my educated guess is at least $0.05/mile to maintain the roads in the condition they should be, e.g., proper ongoing maintenance, resurfacing, etc.) Any significant expansion of the road system would require widespread tolling or additional per mile charges.

In such an environment, rail of all sorts could quickly grow to have an 8%-10% share of total urban travel, and often a much higher percentage of total urban trips (as opposed to passenger miles. I see this coming about in an environment where walking and bicycling are far more important than today, perhaps 30$ to 50% of all trips, versus less than 10% now (with rail being an armature around which urban development occurs, just like before World War II–e.g., lots of streetcar- and railroad-oriented cities and suburbs, where a majority can still have single family houses with more rectangular rather than curvelinear streets–but that’s another screed!) In such a scenario, personal vehicles will still be important, serving less than 50% of all trips but still carrying perhaps 80% of urban passenger miles, as they do in Europe–but 80% of significantly fewer overall VMT per capita, again as typical in European cities now.

CPZ and MSetty,

Let’s see if any of the freight railroads pursue electrification on their lines. If they don’t see any point in it, why should taxpayer funds be used for it?

Nationally, more than two-thirds of our electricity comes from fossil fuels. Until we can reach a consensus on what should replace those sources, it is too soon to talk about rail electrification. And with at least some environmentalists opposing nuclear, wind, new hydro, and most other alternatives, I don’t see a consensus anytime soon.

On the one hand – The Conservative Party in the UK is planning to spend £20bn on 195 miles of high-speed (TGV) rail, or approximately $200m per mile.

On the other hand – By conventional wisdom, there shouldn’t be any heavy rail in the USA at all. The USA came late to building rail. Rail companies in Europe did the maths, and came to the conclusion that by the time rail companies had graded the track bed, bought good quality lumber for the sleepers, etc. rail would be too expensive, at least to cross a continent. The US companies laid the track directly onto the earth, using the worst quality timber they could find. That was their secret.

It all depends on what you want to spend. Necessity, after all, is the mother of invention.

My problem with high-speed rail is that it should compete with private airlines. They build their own terminals, and buy their own airplanes. No private company wants to build high-speed rail, and it only gets bought by governments. This then distorts the market out of shape.

Antiplanner wrote:

“Let’s see if any of the freight railroads pursue electrification on their lines. If they don’t see any point in it, why should taxpayer funds be used for it?”

The distances are too great, which is why the US has historically been reluctant to invest in electrification. The increasing fuel prices in the UK are forcing the UK government to rethink their position. The question is then whether improvements in the diesel traction wouldn’t be better. This has already happened in the UK, where some of the intercity units got new diesel engines – quieter, cleaner, and more efficient.

msetty wrote:

“Only the radical fringe of alternative transportation advocates argue for completion elimination of personal motor vehicles,”

It’s not that radical. It’s certainly not as radical as driving motorised vehicles at high speed through communities, which is the current ‘common sense’.

The challenge is to remove the motorised vehicles in a clever way which improves rather than degrades people’s quality of life. Pedestrianisation has had a chequered history, since often it was done without any thought for the shopkeepers whom the planners were (supposedly) trying to help.

The Antiplanner spoke thus:

“Let’s see if any of the freight railroads pursue electrification on their lines. If they don’t see any point in it, why should taxpayer funds be used for it?â€Â

The problem with this position is that the public has built a massive network of competing highways on which trucks run, and it is well documented that heavy trucks don’t pay their complete way in damage to roadways. One of the things Drake has advocated is a 25% tax credit for railroad capital improvements, including electrification. But he’d limit it for ten years or so, since he figures at least one Class I railroad would make the leap.

One benefit of railroad electrification is not only the diesel fuel not used, but also the diesel fuel not used by trucks when more freight could be diverted to the railroads since electrification can also provide better, faster and more reliable freight service, particularly on transcontinental routes where rail already is competitive for some freight markets (not all by any means).

I meant to finish, once one Class I railroad made the leap to mainline electrification, the others will surely follow to remain competitive.

Mr. King wrote:

“My problem with high-speed rail is that it should compete with private airlines. They build their own terminals, and buy their own airplanes. No private company wants to build high-speed rail, and it only gets bought by governments. This then distorts the market out of shape.”

Well those private airlines are not as private as you think, over the years they have had a lot of access to public money.

Though their are over laps such as Virgin, which has both trains and planes. Also Air France wants to get into the HSR business.

Virgin was even biding for operating the planned FOX HSR line in Florida.

Francis King spake thus:

Well those private airlines are not as private as you think, over the years they have had a lot of access to public money.

Tens of billions in the wake of 9-11, I recall, even Southwest Airlines, which never did show an operating loss on its books.

Someone, I forgot who, once pointed out that the airline industry has never made a net profit over the six decades since World War II, particularly if you figure the value of government funding for airports, the military research that paid for jet technology and electronics, and so forth. I wouldn’t feel too bad if the industry eventually implodes to the only really well-managed carriers I see out there, e.g., Southwest Airlines and a few others. Jet Blue has had some recent problems, but they’re nearly not as stuck in the mud as the so-called “legacy” airlines.

For that matter the “Pan Am” brand name is now a New England based freight rail operation. http://www.panamrailways.com/

I’m also glad to see that this comment thread has been pretty civil, unlike many here that I’ve contributed, er, regurgitated to…

The Antiplanner wrote:

> Let’s see if any of the freight railroads pursue electrification on their lines. If they don’t see any point in it,

> why should taxpayer funds be used for it?

If we want to reduce fossil fuel consumption (and convert from petroleum/carbon-based fuels to electric power generated

from nuclear fuel), then railroad electrification would seem to be a low-hanging fruit (and lots less expensive than

new urban heavy or light rail lines) – and it could be an appropriate way to spend some taxpayer dollars to

implement a policy of reduction in consumption of petroleum products.

> Nationally, more than two-thirds of our electricity comes from fossil fuels.

This is correct. But it seems to me that we should be able to satisfy a large amount of our future demand for

electric power by generating it at new nuclear generating stations.

> Until we can reach a consensus on what should replace those sources, it is too soon to talk about rail electrification.

> And with at least some environmentalists opposing nuclear, wind, new hydro, and most other alternatives, I don’t see

> a consensus anytime soon.

Well, there are many environmental groups that oppose any and all new sources of electric power. We seem

to be about on the verge of disregarding these groups on offshore drilling for oil and gas off of most parts of

the U.S. coastline (which, IMO, is a good idea).

msetty wrote:

> One benefit of railroad electrification is not only the diesel fuel not used, but also the diesel fuel not

> used by trucks when more freight could be diverted to the railroads since electrification can also provide

> better, faster and more reliable freight service, particularly on transcontinental routes where rail

> already is competitive for some freight markets (not all by any means). I meant to finish, once one

> Class I railroad made the leap to mainline electrification, the others will surely follow to remain

> competitive.

Though there were electrified U.S. freight railroads in the past (the B&O in Baltimore; the Great Northern

(now BNSF) through the Cascade Tunnel; the PRR along what is now Amtrak’s N.E. Corridor; the Virginian (now part

of NS) in Va. and W.Va.; the Norfolk and Western (also now NS) in W.Va.; and several others). Most of these

were de-energized in the 1950’s or 1960’s.

CPZ, this would also be a boon for commuter rail operations too.

Though regarding the cost, the government let the genie out of the bottle for roads a long time ago. So frankly the the AP hasn’t really got a right to complain.

As I said before, the US had about 15,500 miles of electrified interurban track. Even if the cost of rebuilding this missing infrastructure were around $3,000,000 a mile. That would still be almost a $47 billion project.

We could also throw in that the US has almost 115,000 miles of railroad track that’s missing, so rebuilding that would be close to $345 billion.

Now that’s nearly $400 billion worth of infrastructure that’s just missing from the US and I haven’t even yet factored in the amount of missing streetcar trackage!

the highwayman wrote:

> CPZ, this would also be a boon for commuter rail operations too.

I don’t think so – since I am interested in providing electrification where it gives us most bang for the buck, which

means places with heavy (in carloading and in volume terms) freight traffic – and I don’t think that those will overlap

much with commuter rail lines.

> Though regarding the cost, the government let the genie out of the bottle for roads a long time ago.

> So frankly the the AP hasn’t really got a right to complain.

Are you claiming that railroads did not get government subsidies? If you are, then you are wrong.

Taxpayer subsidy of railroads in the United States goes back to the 1820‘s, when the State of Maryland

helped to build the Baltimore and Ohio – in large part to keep traffic to and from the states of the

Midwest to the Port of Baltimore.

> As I said before, the US had about 15,500 miles of electrified interurban track. Even if the cost of

> rebuilding this missing infrastructure were around $3,000,000 a mile. That would still be almost a

> $47 billion project.

I don’t know what you are speaking of here – I am speaking of the potential to electrify

Class I mainline railroads in operation today, not “revive” failed railroads (be they

interurban or otherwise) of the past.

I am not much of an expert on interurbans, save for one, the WB&A, which ceased most operations

in 1935. Why did it stop operations then? Because the Maryland General Assembly declined to

continue its real property tax break (in other words, the general assembly cut off its (modest

compared to transit subsidies handed out today) operating subsidy).

> We could also throw in that the US has almost 115,000 miles of railroad track that’s missing,

> so rebuilding that would be close to $345 billion.

Why should taxpayer fund the rebuilding of railroad track that’s neither needed nor wanted?

> Now that’s nearly $400 billion worth of infrastructure that’s just missing from the US and

> I haven’t even yet factored in the amount of missing streetcar trackage!

Missing in most cases because it was not wanted and no longer needed, perhaps because those

tracks were no longer economically productive.

Well then CPZ, what you are pushing is for double standards.

Rail and road complement each other, but having transport policy aspects that are like moving goal posts don’t help the situaton.

Francis King wrote:

> On the one hand – The Conservative Party in the UK is planning to spend £20bn on 195 miles

> of high-speed (TGV) rail, or approximately $200m per mile.

But at least at this time, are not the Tories in the minority in the U.K. House of Commons?

> On the other hand – By conventional wisdom, there shouldn’t be any heavy rail in the USA

> at all. The USA came late to building rail.

Rail as in railroads?

Late? As in the 1820’s?

> Rail companies in Europe did the maths, and came to the conclusion that by the time rail

> companies had graded the track bed, bought good quality lumber for the sleepers, etc. rail

> would be too expensive, at least to cross a continent. The US companies laid the track

> directly onto the earth, using the worst quality timber they could find. That was their

> secret.

Not always. The early Baltimore and Ohio used ties (“sleepers”) made of stone – as in granite

> It all depends on what you want to spend. Necessity, after all, is the mother of invention.

Agreed.

> My problem with high-speed rail is that it should compete with private airlines. They build their

> own terminals, and buy their own airplanes. No private company wants to build high-speed rail,

> and it only gets bought by governments. This then distorts the market out of shape.

I agree.

> Antiplanner wrote:

>

> “Let’s see if any of the freight railroads pursue electrification on their lines. If they don’t

> see any point in it, why should taxpayer funds be used for it?â€Â

>

> The distances are too great, which is why the US has historically been reluctant to invest in

> electrification. The increasing fuel prices in the UK are forcing the UK government to rethink

> their position. The question is then whether improvements in the diesel traction wouldn’t be

> better. This has already happened in the UK, where some of the intercity units got new diesel

> engines – quieter, cleaner, and more efficient.

Certainly improved Diesel locomotive technology is one way to reduce fuel consumption.

Regarding electrification in the U.S. On many parts of the U.S. Class I railroad network, it

does not make sense now, and may never make sense. But on the other hand, there are places with

steep grades and heavy loads where it might make a lot of sense.

> msetty wrote:

>

> “Only the radical fringe of alternative transportation advocates argue for completion elimination

> of personal motor vehicles,â€Â

>

> It’s not that radical. It’s certainly not as radical as driving motorised vehicles at high speed

> through communities, which is the current ‘common sense’.

>

> The challenge is to remove the motorised vehicles in a clever way which improves rather than degrades

> people’s quality of life. Pedestrianisation has had a chequered history, since often it was done

> without any thought for the shopkeepers whom the planners were (supposedly) trying to help.

Getting high-speed vehicular traffic out of neighborhoods is a great idea. Hence improved arterial

roads, and limited-access highways (including toll roads).

I’m just waiting for someone to pine about the days when the Milwaukee Road was electrified. 🙂

Though toll roads aren’t always limtited access, hey I even konw some residential streets that only 100 years were toll roads.

the highwayman wrote:

> Though toll roads aren’t always limtited access, hey I even konw some residential

> streets that only 100 years were toll roads.

How is that relevant? Or are you just here to make troll-like comments on this blog?

The vast majority of toll roads in the U.S. today are limited

access. There are some toll crossings (e.g. bridges and even a ferry or two) which

are on arterial highways.

100 years ago there were relatively few motor vehicles on our roads. But there were many

19th Century turnpikes which served horses and horse-drawn traffic. One of the longest

and best-known was the National Road (U.S. 40 today) which ran from Cumberland, Maryland

to Vandalia, Illinois.

NYC is resorting to ads on subway cars to help recover from an anticipated $900 MILLION shortfall next year. This, in the face of increased ridership, mind you.

http://wcbstv.com/watercooler/subway.car.advertising.2.830528.html

The prime candidate for electrification is the line between California and Illinois, most especially the California-Nevada section. This line carries the overland portion of container shipments of goods moved from Asia to the U.S. The combination of steep grades and the one-way movement of mineral ores on the Nevada-California segment could result in regenerative braking from westbound trains powering eastbound trains.

AP wrote “Until we can reach a consensus on what should replace those sources, it is too soon to talk about rail electrification. And with at least some environmentalists opposing nuclear, wind, new hydro, and most other alternatives, I don’t see a consensus anytime soon.”

That’s part of the reason why market forces are encouraging innovative small-scale distributed renewable generation and conversion technologies. These are technologies that often don’t require permits or only require permits for the the strength of the building they are attached to or incorporated into.

The market penetration of conversion technologies is difficult to measure because energy is being directly converted from wind or sunshine into usable heat or mechanical energy and therefore doen’t get included in conventional energy usage stats because those stats actually measure energy trades rather than energy consumption.

In the case of rail electrification we could see a return to the economics of the early subway and streetcar suburbs. Rather than simply electrifying the freight lines the railroad companies may use their rail corridors as locations for wind turbines and distribution lines. That way existing tax credits for grid electricity investments can be used to offset the capital costs of electrifying the rail lines and the rights of way provide additional revenue streams. The airspace above a railroad corridor is more valuable for wind generation than farmland simply because there is no need to negotiate with multiple land owners for the RoW for transmission lines.

CPZ wrote:

“How is that relevant? Or are you just here to make troll-like comments on this blog?”

Well I don’t live under a bridge and I don’t ask for money so travelers can cross.

Troll bridges instead of toll bridges.

“The vast majority of toll roads in the U.S. today are limited

access. There are some toll crossings (e.g. bridges and even a ferry or two) which

are on arterial highways.

100 years ago there were relatively few motor vehicles on our roads. But there were many

19th Century turnpikes which served horses and horse-drawn traffic. One of the longest

and best-known was the National Road (U.S. 40 today) which ran from Cumberland, Maryland

to Vandalia, Illinois.”

I know, why should tolls only be collected on certain roads?

Kevyn Miller wrote:

“In the case of rail electrification we could see a return to the economics of the early subway and streetcar suburbs. Rather than simply electrifying the freight lines the railroad companies may use their rail corridors as locations for wind turbines and distribution lines. That way existing tax credits for grid electricity investments can be used to offset the capital costs of electrifying the rail lines and the rights of way provide additional revenue streams. The airspace above a railroad corridor is more valuable for wind generation than farmland simply because there is no need to negotiate with multiple land owners for the RoW for transmission lines.”

In a strange way Amtrak wanted to do some thing kind of like this on the NEC.

http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-301.html

Any ways lets just be honest in that the current transport policy that exists here in North America is on a 4th world level and that we have a long way to go to turn things around.

The current highway welfare system is bankrupting us and a great chunk of our rail system is deliberately missing.

HSR is 100% viable, along with conventional trains and trams. The problems we face are not technical, but political. Though a lot of social engineering that has been done by the auto industry has to be over come, to reclaim our freedom.

The current highway system is bankrupting whom? Canada? US? Mexico?

Pingback: » The Antiplanner

prk166, stop being a dumbass.

Randall your agenda is very simple to understand, why undo damage to our economic frabric, when you can cause more.

I used to live in Northern California “Bay Area” so I’m no stranger to HSR (high speed rail) proposals.

My friend once said, “This proposal would be wonderful. Imagine being able to travel down to Los Angeles in 2.5 hours!”.

I replied, “Yeah and once you get there you’ll need to rent a car. You can’t move around in LA without a car, no exceptions. If that’s the case I’d rather just drive all the way down.”

That is exactly why HSR will never work in California.

But have no worries that state is so grossly financially mismanaged it would take a miracle for California to just come up with the funds to maintain existing infrastructure let alone expand it.

Then by your logic the state of California should shut down those expensive freeways.