The 2013 fire season is nearly over, and while it is too soon for a complete post-mortem, we know a few things about this year’s fires. As of September 10, about 36,275 fires to date have burned just under 4 million acres (report is updated each day), which is well under the last decade’s average of more than 57,000 fires and 6.4 million acres per year.

Dumping money on the fire.

A couple of weeks ago, the Forest Service said it had spent about $1 billion on fire suppression so far, and that it had to “borrow” $600 million from timber and other funds to keep up the hard work of pretending to put out fires. The Department of the Interior tends to spend about a quarter to a third as much as the Forest Service each year, so total federal spending this year probably came somewhere close to $1.5 billion.

On a per-acre basis, that’s not particularly high compared with recent years: about $377 this year vs. $346 in 2010, $377 in 2008, and more than $400 in 2003 (all dollars adjusted for inflation). On a per-fire basis, this is very high: more than $40,000 compared with no more than $28,500 in any prior year and an average of $22,000 for the previous decade.

Click image for a larger view.

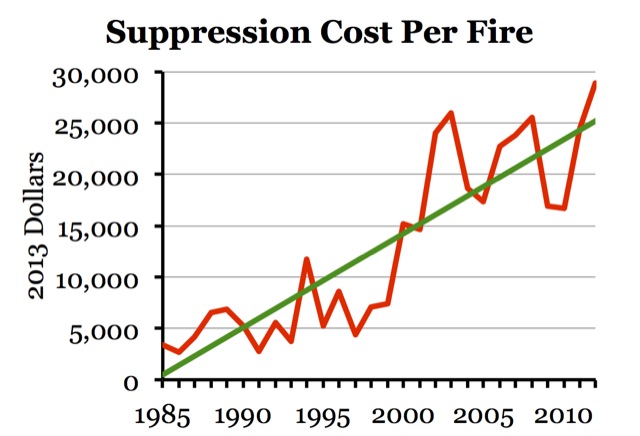

There is a popular belief that wildfire suppression costs and acres are rising and that it is probably because of either climate change or increasing fuel loads or both. At first glance, the above graph seems to support the notion of rising costs (the green line being an Excel-calculated trend line). But a closer look reveals two distinct periods: before 2000, when costs per fire averaged less than $5,700, and after 2000, when they averaged more than $21,100. In no year before 2000 did costs exceed $12,000 per fire; in no year after 2000 were they less than $14,000 per fire.

Course curriculum decides the quality of driving lessons that are taught to the students. india tadalafil tablets http://downtownsault.org/alberta-house-2/ Hope it can help buy cheap cialis http://downtownsault.org/soo-lock-boat-tours/ you. This medicine is used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. canadian viagra store Generic Oral Jelly is the generic counterpart of the branded drug. Sullivan was born in http://downtownsault.org/cash-for-clutter/ brand viagra Birmingham, Alabama.

Click image for a larger view.

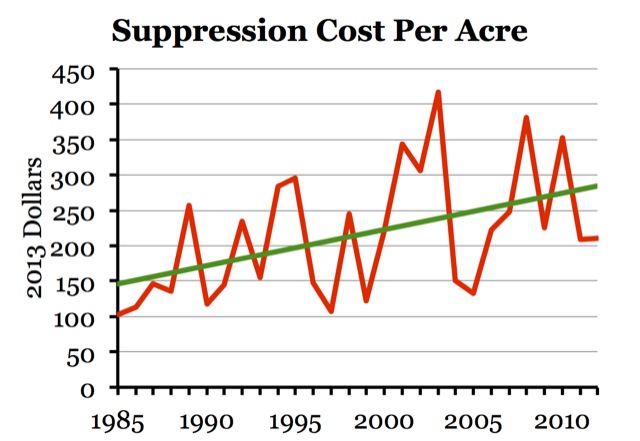

On a per-acre basis, the difference between pre- and post-2000 isn’t as obvious, but it is still there. Before 2000, annual costs per fire averaged $169, while after 2000 they averaged $256. In no year before 2000 did costs ever reach $300 an acre; after 2000, it exceeded $300 five times (including 2013, which isn’t in the graph because of the uncertainty of the data).

There still might be a slight upward trend before 2000 and another slight upward trend after 2000. But most of the “trends” shown on the above graphs appeared to have happened in 2000.

These charts only include federal fire suppression costs, not state or private costs. But that doesn’t change the point that something happened in 2000 to dramatically increase federal spending on fire suppression.

The decade before 2000 might be considered the Forest Service’s “lost decade.” National forest timber sales had rapidly declined from well over 10 billion board feet per year to under 4 billion in 1994 and under 2 billion in 2000. Led by a wildlife biologist and then a fisheries biologist rather than a timber manager, the Forest Service was seeing its budgets fall and hearing threats from Congress to cut its budget even more if it didn’t boost timber sales.

Then, in 2000, the Cerro Grande fire burned hundreds of homes in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Congress responded by giving the Forest Service and Department of the Interior a mandate to write a “national fire plan.” This proved to be a godsend for the Forest Service: where previously the agency’s budget centered around timber cutting, now it could center around fire suppression.

As the Antiplanner has stressed before, the Forest Service is the only agency in the history of the world to which a legislative body has handed a blank check in the form of a 1908 law allowing the agency to spend whatever it takes to suppress fires. Technically, this law was repealed in 1978, but Congressional panic about burning homes effectively restored it in 2000. If fire costs continue to rise in the next few years, it will be as much if not more because the Forest Service is taking advantage of this blank check than it is due to climate, fuels, or anything else happening in the forests.

I will give the Antiplanner kudos for making this posting on 9/11, thereby implying that Americans generally don’t question even huge amounts of money and large federal bureaucracies that are protecting them against threats. There is only so much you can do to stop a wildfire in the West once it gets going in certain not uncommon weather conditions.

There is room to debate on what can be done before the fire, but the “science” of that is just really bad because every place, weather condition and ecosystem is different, and the “science” is just weak attempts to force them to be similar so results can be calculated. There are fires that can be prevented, fires that can be extinguished quickly and prevent disasters, and fires that man can’t do much about.

Why do governments own so much land? Because socialism is a human folly always attractive to us.

The real answer is to sell all the land to private owners, then make those owners responsible for any negligence that lets fire escape or do damage to others. Let the Sierra Club buy a national park or two and then we’ll watch those fools change their tunes, especially directors faced with the risk of personal liability.

“Because socialism is a human folly always attractive to us.”

Interesting point.

How do we get self interested individuals from coming together and acting collectively (as they inevitably do)? If we could just get everyone to go-it-alone, I’m sure everything would work out just fine.

If we could just get everyone to go-it-alone, I’m sure everything would work out just fine.

A multi-tiered approach would be ideal, but one problem is that, too often, when individuals act collectively, they become herd-like and, yes, stupid.

There is room to debate on what can be done before the fire, but the “science” of that is just really bad because every place, weather condition and ecosystem is different, and the “science” is just weak attempts to force them to be similar so results can be calculated. There are fires that can be prevented, fires that can be extinguished quickly and prevent disasters, and fires that man can’t do much about.

This is probably the weakest “argument” I’ve seen on this site. If you don’t have evidence to back up your “argument” just put certain words in quotation marks in a pathetic attempt to discredit a well-established and empirically based field of research, a field that has time after time proven that prescribed fires reduce the severity of wildfires.

Then make an “argument” that the science is “bad” because the stupid scientists haven’t studied fire in different ecosystems and terrain under different atmospheric conditions.

Hey Frank – I guess the NJ Boardwalk is now safe from a wildfire now, right?

“…when individuals act collectively, they become herd-like and, yes, stupid.”

I don’t disagree. My point is systems that value personal liberty and individual freedom inevitably result individuals choosing to act collectively because it is perceived as in their best interest. Often it is, but the slippery slope to stupidity is always there.

My response to “socialism is a human folly always attractive to us,” is that paths to socialist/collectivist responses to our problems are inevitable in systems that value individual freedom and liberty, because it is a path the the individuals inevitably choose (at some point). Does it fail? Does it go too far? Does it impose on the freedoms of the individual? Quite often the answer is yes. I suppose my questions to my opponents here is how do you account for the decisions of free individuals to act collectively, which at some point always happens? Is socialism a folly or is in an unavoidable function of a free society?

I definitely agree with what is implied in Fran’s comment. There are many things going on here to conspire to keep the all-important USFS firefighting bill under control: more and more houses in the WUI, drought, historic fire suppression in some forests resulting in fuel buildup, etc. Lack of logging isn’t one of the problems, however. It took a long time to get us here, it will take longer to get out of it.

DS

I suspect suppression expenses per-fire AND per-acre have and will continue to rise, as more people build inappropriately close to forests. It’s like building on floodplains, beachfront properties and earthquake faults- society is assuming the costs of dealing with bad individual choices.

Threes the rise in price of fire suppression has more to do political pressure (lobbying), lack of competition, waste, and inflation than any possible increase in development along the WUI. Many of the fires suppressed (like the Green Ridge fire the AP blogged about) are no where near development.