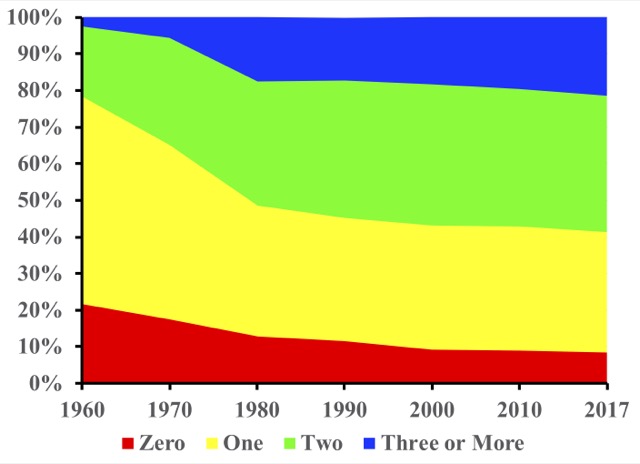

Supposedly, young people today prefer to rent multifamily housing over buying single-family housing. This claim is used to justify policies aimed at densifying cities by rezoning neighborhoods of single-family homes for multifamily housing. As the New York Times Timothy Egan writes, “An unholy alliance of socialists and developers threatens to destroy the city’s single-family neighborhoods with a major upzoning.”

Data from the 2017 American Community Survey can help put this claim to the test. Table B25125 breaks down housing into six types: single-family, multi-family, and other (mobile homes, boats, RVs, vans), each owned or rented, and reports for householders (one of the adults in the household) of ages 15-34, 35-64, and 65-plus. We can compare the results with table HCT004 from the 2000 census to see how young people (and middle-aged and seniors) lived in 2017 vs. how they lived 17 years before.

In 2017, 29 percent of householders under 35 owned and 20 percent rented a single-family home, while 2 percent owned and 44 percent rented multifamily housing. But that’s not much different from 2000, when 31 percent owned and 16 percent rented a single-family home and 2 percent owned and 42 percent rented multifamily. Continue reading