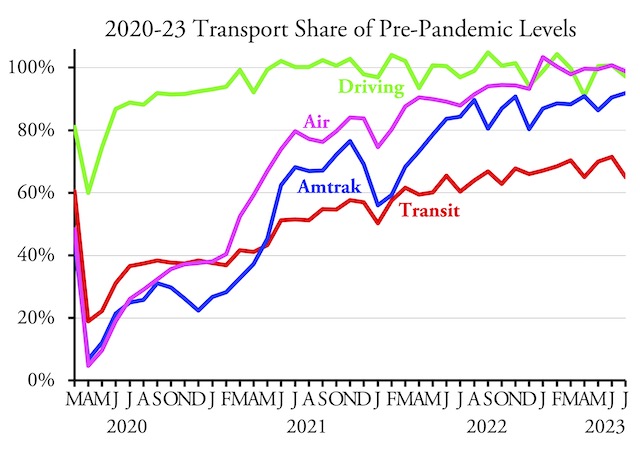

About 5.0 million Americans relied on transit to get to work in 2022, according to American Community Survey data released by the Census Bureau last week. This is more than the 3.8 million people who took transit to work in 2021, but far less than the 7.8 million to used transit in 2019. People who used transit represented 3.1 percent of the workforce, up from 2.5 percent in 2021 but down from 5.0 percent in 2019.

There was about 6 percent more commuter traffic on the roads in 2022 than 2021, but still about 7 percent less than 2019. Photo by Tomi Knuutila.

Transit’s share is strongly skewed by New York City, which housed 2.5 percent of the nation’s workers but 34.6 percent of the nation’s transit commuters in 2022. Outside of New York City, only 2.1 percent of workers relied on transit to get to work in 2022. That’s just the city: the New York urban area had 45.4 percent of the nation’s transit commuters, and outside of that area only 1.8 percent of workers relied on transit. Continue reading