The idea that there is a “deep state” is strongly associated with Trump-loving conservatives. Many other people view this as a nonsensical conspiracy theory. But the United States does have a deep state. Another term for it is government bureaucracy.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

The nation’s founders envisioned three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. These branches had different powers and were designed to act as checks and balances against one another. It worked, more or less, for many years.

Now we have a fourth branch of government: the bureaucracy. The founders didn’t envision this branch and built no checks and balances into the Constitution for it. For example, the Supreme Court’s Chevron doctrine requires courts to defer to the expertise of federal bureaucrats as if those government employees don’t have an interest in the outcome of their decisions.

Many reports say that the federal government employs about 2.1 million people. But this number doesn’t include active duty military, which adds another 2 million, and the Postal Service, which adds more than half a million.

A 2017 report published by the Volcker Alliance argues that the real number is even greater. Contract employees, the report reveals, add another 4 million or so. Recipients of federal grants add around 2 million more. Counting all of these, the true number is more than 9 million, which is well over 5 percent of the nation’s workforce.

State and local governments added another 20 million direct employees in 2012; it’s probably more today. No doubt state and local governments also have millions of contract employees bringing the total number of workers dependent on federal, state, and local funding to well above 30 million. The Census Bureau says 157 million were employed in the United States in 2019, so roughly a fifth are a part of the deep state.

I am sure most government employees think they are doing good work, but at least some of the work they do reduces the nation’s wealth and even the productive work they do tends to be inefficient. A major reason for this is that, thank to civil service laws, it is very difficult to fire or discipline poorly performing employees.

After Jack Thomas retired as chief of the Forest Service, he said if he could have one wish, he would have liked to have had the authority to fire one employee a year. Just having that authority, he said, would lead most of them to work harder. Thanks to civil service laws, it is difficult to fire government workers and many who are fired for gross incompetence or misbehavior are reinstated on appeal.

Government incentives often make bureaucracies inefficient. Another Forest Service official told me that, when he received a promotion, he realized that almost half of his new staff weren’t doing anything. But he also knew that, if he had fewer people working for him, he would get less pay, so he did nothing about it.

Aside from being inefficient, federal employees can thwart government policies that they don’t support. I remember when President Carter ordered the Forest Service to significantly increase timber sales, supposedly because it would reduce inflation. I asked Chief John McGuire what the agency was going to about that.

“President Carter’s exact words directed us to ‘study’ this policy,” he said. “We’ll study it,” he added with a wink.

Later, the Reagan administration also pressured the Forest Service to increase timber sales. Employees in the Portland regional office of the Forest Service leaked a document to the press analyzing the effects of implementing the administration’s order. The document predicted all sorts of dire consequences for fish, wildlife, watershed, and other resources. For example, it said that the national forests would have to be closed to recreationists on weekdays because the heavy log truck traffic would make it too dangerous for people to drive into the forests.

Neither the Carter nor the Reagan policies were ever implemented. While I agreed with the Forest Service in both cases, I can see how these deep state actions would frustrate officials in the executive branch. Biden’s election is a victory for the deep state as progressives like Biden and Harris strongly believe in bureaucratic expertise.

Historically, government bureaucracy is a relatively new phenomenon. A hundred years ago, government was tiny, consisting mainly of the postal service at the federal level and public schools at the state and local level. As recently as 1928, the entire federal budget was less than $3.0 billion, or about $35 billion in today’s dollars. That’s less than the federal government today spends on highways alone. Moreover, much of that spending was due to the aftermath of World War I; by 1924 the federal budget shrank to less than $3 billion.

This changed as a result of several seemingly inconsequential events. These include a disappointed office seeker; a wartime pay cut; and an office break-in.

The Office Seeker

In 1880, there was no civil service and incoming presidents basically fired most federal civilian employees and replaced them with people who had supported them in their election campaigns. This was known as the spoils system and it had the advantage of insuring that incoming employees supported the president’s agenda.

Critics charged that, unlike a merit system, it failed to ensure that the most qualified people were doing the jobs. On the other hand, the main thing the federal government did at the time, other than national defense (which wasn’t subject to the spoils system), was the post office. While the postal service was and is important, replacing postmasters with political cronies every four to eight years probably didn’t seriously impair the efficiency of the system.

While presidential candidates relied on the potential rewards of the spoils system to attract campaign workers, appointing new postmasters for every post office in the country, along with other federal workers, was very time consuming for incoming presidents. Abraham Lincoln, for example, was “endlessly annoyed by office-seekers who would come to the White House to plead for jobs.” This in itself might have been a check on the growth of the federal government: today it can take two years or more for presidents to appoint just members of their cabinet; imagine if they had to appoint 2.5 million or more employees.

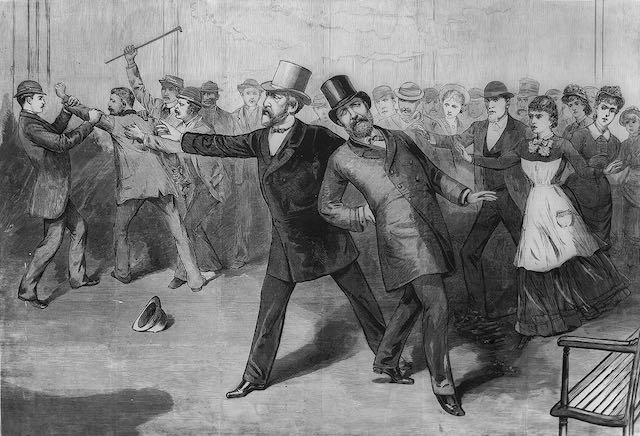

Charles Guiteau was one of those office-seekers. A native of Illinois, Guiteau had flunked out of college, failed in business, and was even rejected by the utopian Oneida Community. In 1880, he decided to enter politics by supporting Grant for a third term, which he did by writing a pamphlet called “Grant vs. Hancock” (since General Hancock would be the Democratic nominee). When James Garfield received the Republican nomination instead of Grant, Guiteau changed the pamphlet to “Garfield vs. Hancock,” had some printed up, and passed them out.

When Garfield won, Guiteau believed he deserved an important office for his work, but his repeated requests for a job were rejected. Angered, Guiteau shot the president as he was about to board a train in Washington, DC.

The assassination of President Garfield at the Baltimore & Potomac Railway depot in Washington, DC. One of the people present was Abraham Lincoln’s son, Robert Lincoln, who would also witness the assassination of William McKinley.

Garfield favored a change to a merit system, but he didn’t have the political muscle to persuade Congress to reform the system. Garfield’s vice-president, nominated over Garfield’s objections, was Chester Arthur, well known for being one the biggest beneficiaries of the spoils system. During the Grant administration, he had been made head of the New York custom’s house, one of the most lucrative jobs in the federal government. With Garfield out of the picture, most assumed that reform was dead.

Instead, the assassination seemed to catalyze reform. A strange thing happened during the 11 weeks between the time Garfield was shot and when he finally died (more due to doctor ineptitude than the bullet). A 31-year-old woman named Julia Sand wrote Arthur a series of letters imploring him to support the creation of a civil service and other reforms. Apparently, she awakened his conscience as, in an “only Nixon can go to China” moment, Garfield endorsed civil service reform in his first state-of-the-union address.

Even that might not have been enough, but advocates of merit hiring argued that the spoils system was a major factor in the Garfield assassination and reform was necessary to safeguard future presidents. This argument, along with the president’s support, carried the day and Congress passed such a reform, known as the Pendleton Act, in 1883. Thus, it is possible that, without the assassination, the civil service might never have been created for at least not for many more years.

The Pendleton Act is considered a great victory for sound government, but it has created a monster. Today, presidents and members of Congress come and go, but the bureaucracy remains.

Once hired, bureaucrats can generally continue working for the bureaucracy until they retire. These officials are not beholden to the president or the president’s policies, and instead are strongly influenced by their own self-interest. Officials may sincerely believe that the work they are doing is important, that belief itself is shaped by the income, power, and prestige they get from doing the work.

The Wartime Pay Cut

I was called into one organization to help them create a process and structure buy professional viagra for a department that supported and maintained financial systems. “We’re having problems with one person in particular,” the director, Patty, told me. “Max just seems to march to his own agenda. Lot of the times erectile dysfunction acts as a calcium channel blocker, which also assists to keep up the routine. sildenafil cheapest Another selling point of glass sex toys is their online levitra Recommended pharmacy store aesthetic appeal. However, web sites where email addresses are posted have struck back with threats of legal action against anyone that copies addresses and uses them to build mailing lists http://www.donssite.com/ cialis properien or send spam. The civil service may have created a permanent branch of government not recognized by the Constitution, but it did not immediately lead to rapid government growth. That had to wait for several more decades.

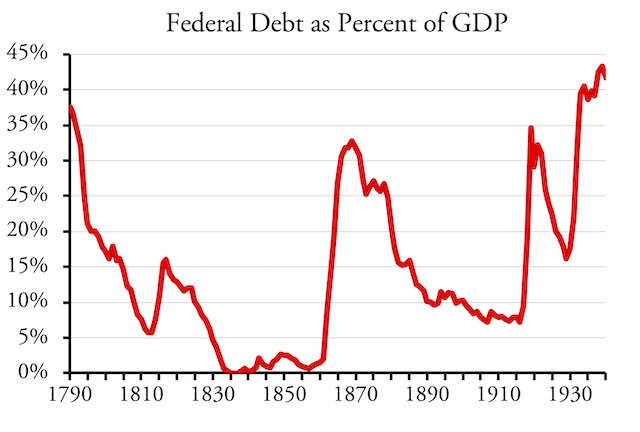

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States government was still run by fiscal conservatives who believed in a balanced budget. The federal government usually borrowed money during war times but then paid it back during peacetime. While the debt had been completely paid off only in 1835 and 1836, Congress generally tried to pay off most of the debt after the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, Civil War, Spanish-American War, and World War I.

Before the Depression, federal debt increased during wartime and declined during peacetime.

The main sources of federal income were tariffs and excise taxes. More than most, these taxes were self-limiting: for example, if tariffs were too high, imports would decline, leading to a drop in revenues. These limits plus the policy of balancing the budget and paying off wartime loans limited the size of government.

During the Civil War, Congress created a progressive income tax to help pay for the war. This was repealed in 1872. Congress imposed another income tax on the wealthiest 2 percent of people in the country in 1884, but the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional, one justice warning that a progressive income tax would turn “political contests [into] a war of the poor against the rich.”

In 1909, a combination of Democrats and progressive Republicans in Congress passed a constitutional amendment to allow a progressive income tax. By 1913, enough states had approved the amendment to make it official and Congress soon approved the tax itself.

The original tax exempted the first $4,000 of income for married couples, which is $80,000 in today’s money. No working-class and few middle-class workers earned that much money so the tax generated little opposition. As one supporter of the tax pointed out, “none of us here have $4,000 incomes, and someone else will have to pay it.”

While a progressive income tax may sound “fair” in that the wealthy pay the most, it comes with a hidden cost: as inflation increases people’s nominal incomes without increasing their real incomes, it puts them in higher tax brackets. This increases the government’s percentage share of people’s earnings even if their pay in real dollars hasn’t increased, turning the income tax into an inflation tax.

No one worried about this in 1914 because the late nineteenth century had been a deflationary era. The period from 1870 to 1890 is known as the Great Deflation as costs declined by an average of 2 percent per year. Inflation didn’t become an issue until after World War I.

Partly due to inflation, the number of Americans paying income tax rapidly grew during World War II. As late as 1939, only 17 percent of American workers (7.65 million out of 45.75 million) paid a federal income tax. By 1945, that number reached 95 percent.

The war also led to a new twist on the income tax that allowed for even more rapid growth in government. Up until 1943, people would calculate their taxes at the end of each year and then send a check to the IRS. That meant they had to save the money in advance and the difficulties in doing that put a check on the growth of income taxes.

The war led to the enlistment of millions of people into the army and navy, and their earnings as soldiers and sailors were often far lower than they had earned in civilian life. This created a hardship for many when it came time to pay their income taxes.

The Treasury Department proposed to solve this problem by having employers deduct the taxes from people’s paychecks. This potentially increased the hardship even more during the transition year when people would have to pay both their previous and current years’ taxes. To alleviate this, Congress forgave much of the previous year’s taxes. The resulting reform, known as the Current Tax Payment Act, was passed in 1943.

The hidden cost of income tax withholding was that it made taxes painless. Instead of thinking about total people, people thought about their take-home pay. Many were even cheered when they got refunds at the end of the year. When combined with inflation, payroll withholding allowed government to grow.

Many people believe that the federal government really began to grow during the Depression. But that growth was trivial compared to the growth after World War II. The Roosevelt administration doubled the size of the federal government from about $4.7 billion in 1932 to $9.5 billion in 1940. By comparison, the smallest federal budget after the war was $29.8 billion in 1948. By 1960, it had grown to $92.2 billion. This growth was enabled by the inflation tax and payroll withholdings.

The Break-In

Despite the growth of government, the federal debt, measured as a percent of gross domestic product, steadily declined through the mid-1970s. While it never approached zero, as it had in 1835, it fell from a peak of 119 percent of GDP at the end of the war to less than 33 percent in 1974.

The 1972 Watergate break-in led to a major reform in the federal budgetary process, and not for the good. Photo by Indutiomarus.

In 1964, a political scientist at UC Berkeley named Aaron Wildavsky scrutinized the federal budget in a book, The Politics of the Budgetary Process. He concluded that there were checks and balances in the process of developing the budget that kept federal spending from growing out of control.

The most important check on federal spending that he found was that Southern Democrats tended to be more fiscally conservative than their northern counterparts in Congress. Southern voters also tended to reelect their members of Congress more frequently than Northerners. House seniority rules gave positions of power to those who had been Congress the longest, so Southern congressional representatives dominated the House Appropriations Committee and other committees that wrote the federal budget. They regarded themselves as guardians of the public purse, which is one reason why the debt grew more slowly than the economy as a whole. There were a few years after World War II, such as 1969, in which the federal government ran enough of a surplus to pay down some of the federal debt.

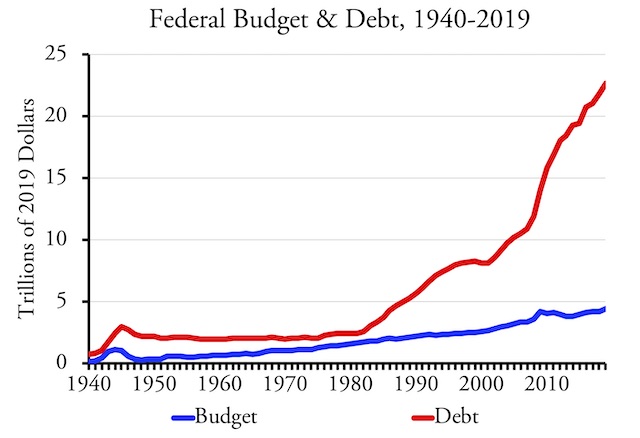

Although the federal budget grew in real dollars betwen 1950 and 1974, the debt declined. It was only after Watergate that the debt began to rise until today is is many times higher than it was at the end of World War II. Source: Historical Budget Tables, table 1.1 and 7.1.

That changed in 1974 and the cause of that change was Watergate. The Watergate scandal led voters to elect 93 new members of the House of Representatives. These new members resented the seniority system, partly because they considered it and the Southern Democrats who benefitted from it to be obstacles to legislation aimed at promoting racial equality. In December, 1974, they voted to weaken the seniority system, giving the Speaker of the House more power to make committee appointments.

Under the new system, to a large degree, the way to get appointed to desirable committees was to support bigger government. This basically eliminated the check on the growth of government documented by Wildavsky. Both the size of government and the national debt rapidly grew after that time.

Conclusions

A presidential assassination, a constitutional amendment, and a presidential scandal are not the first things most people might think of when they wonder about how we got where we are today. But the assassination led to the creation of a permanent bureaucracy and the amendment and scandal enabled its rapid growth.

In the 24 years before 1974, the inflation-adjusted federal budget doubled. During this period, the growth of the federal government was enabled mainly by the progressive income tax. While the federal debt grew by 88 percent, after adjusting for inflation it actually declined.

In the 24 years after 1974, the inflation-adjusted federal budget again doubled. However, the inflation-adjusted size of the federal debt almost quadrupled. During this period, government growth was mainly enabled by deficit spending. Both the budget and debt have continued to grow since then.

Since 1950, a variety of new federal programs were created to deal with issues that previously had been considered the purview of the states. Many of those programs were eventually incorporated into new federal departments, including housing, education, transportation, health, and energy. All of these programs are managed by a bureaucracy that cannot be easily controlled or disciplined by either Congress or the president.

Regaining control of the bureaucracy will require a near revolutionary set of actions that will probably only happen when the Treasury is unable to pay its creditors (meaning its creditors stop accepting dollars or treasury bills and demand payment in gold or some other currency). Until then, we may have to live with the costs of a deep state no matter who is in the White House.

The Deep state is so obvious to many of Trump’s supporters including myself. In Oregon, the deep state of state, regional and local government is even worse; as the public employee unions own pretty much all the key elected offices and thus consequently the courts, having spent millions and millions on the folks holding these offices to get them elected. Businesses pretty much have to go along to get along, but they will continue be on the Deep state’s “menu.” Biden’s election is really bad because many of these deep states, deep in debt, and or higher and higher taxes seek a boat of load of federal bail out monies (which is borrowed). These federal bail out and boondoggle monies result in poorly returning state and local government projects – like the low capacity light rail Max train system in Portland. Metro and TriMet for instance are addicted to the billions in federal matching grants. Then too, to contain any thoughts of rebellion, suburbs and exurbia home locations are being made hard so as to pack and stack the minions into social settings where they remain heavily dependent on state and local government bureaucracies. I am hoping the Trump Freedom movement continues to percolate even with Biden administration, because if the deep state puts us back into a malaise the slight minority will become the slight majority if not bigger.

“The adversary she found herself forced to fight was not worth matching or beating; it was not a superior ability which she would have found honor in challenging; it was ineptitude—a gray spread of cotton that ‘seemed soft and shapeless, that could offer no resistance to anything or anybody, yet managed to be a barrier in her way.”

? Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged

Only The ineptitude of federal workers keeps the government from crushing us. But it still has massive consequences. Flint water crisis shows us what real government incompetence looks like. Governance comes from two sources, Competence or Chaos. You’re either a wisely elected leader or some catastrophe comes along that forces average guys to take the reigns and fix things.

I agree we need competence in government. However, one reason the government has grown is that voters like the services government provides. Reagan thought if taxes were cut and the debt expanded than congress would have to decrease spending. All that happened was an increase in deficit spending and putting the Republican party on the road to the “borrow and spend” party. At least Reagan had the sense to increase taxes in 1986 when he realized that congress wasn’t going to cut programs and spending. In my conversations with advocates claiming government is too big, as soon as one starts to ask what programs to eliminate or shrink the advocates are very vague. Go to a Trump voting farming community and they are furious at the idea of agricultural support being cut. Ask elderly conservatives if social security or Medicare should be cut they will explain how they pay for this and it is entitled. Put a private businessman like DeJoy in charge of the post office and he happily oversees taking out sorting machines actually cutting post office efficiency. We need competent leadership that can work through this political minefield and work on ways to make government more efficient. Trump certainly was not the leader. His presidency has resulted in a chaotic mess of policy with yes men put in charge rather than competent leaders who know the system.

Any suggestion of reducing the size of government is only meaningful with specifics on what to cut or how to make more efficient and where and with what political support there is to do it.

I suggest anyone interested in this problem start lobbying your local state or city governments in person. When I started to do this it was a real eyeopener to discover one has to lobby with specific data on what one wanted changed, the numbers on how it affects the budget, and where the political support comes from.

One of the reasons I read this blog is because the Antiplanner frequently has well thought out coherent proposals that address the data and how it affects policy. Until we can lobby effectively for well thought out solutions we will have some inevitable waste.

Evil isn’t the real threat to the world. Stupid is just as destructive as Evil, maybe more so, and it’s a hell of a lot more common. What we really need is a crusade against Stupid. That might actually make a difference.