By Elijah Gullett

Note: As a follow-up to my report on low-income housing tax credits in Seattle, I asked Elijah Gullett, who is a student in public policy at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, to look at affordable housing programs in Miami. This is his report.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

In 2007, journalist Debbie Cenziper won the Pulitzer prize for her Miami Herald investigative series, House of Lies. Cenziper revealed how Oscar Rivero, a Miami developer, ripped off taxpayers by promising the construction of affordable housing units and inflating construction costs for his own profit. In 2016, Lloyd Boggio and Matthew Greer, former CEOs of Carlisle Development Group, were found guilty of defrauding the government for affordable housing construction. Despite Carlisle being praised for their work in constructing “high-quality” low-income housing in Miami, they stole tens of millions of taxpayer dollars by inflating construction costs and making backroom deals with contractors. Even more recently, Pinnacle Housing Group and Related Group have been investigated for padding construction costs to steal money from government programs.

These are not merely disjointed stories of corruption – they are indicative of the widespread fraud and corruption in affordable housing construction in Miami, Florida. The same patterns of inflating construction costs to steal more money from government-run affordable housing programs by both for-profit and non-profit groups keep reappearing. This is no accident; this type of corruption is built into the very structure of America’s largest affordable housing program: the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).

How LIHTC Works

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, also known as Section 42 housing, is a federal program that attempts to increase the supply of affordable housing units for low-income Americans through subsidies to private and non-profit development firms. It was part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, a massive Reagan-era bill that attempted to simplify and reduce taxes. The LIHTC program was designed to improve upon America’s failed earlier public housing programs by creating public-private partnerships in the development of affordable housing. Since then, a booming affordable housing industry has developed around the program that involved private development firms, investors, non-profits (Habitat for Humanity and local organizations), and private consulting firms.

LIHTCs are administered by the federal government’s Housing and Urban Development (HUD) agency, and tax credits are allocated to states based on population size, incentivizing construction in large states without regard for state housing cost burdens. State-level housing financing agencies then distribute these tax credits to for-profit development companies and non-profits. Companies and non-profits will estimate how much their proposed affordable housing development will cost, and the state housing finance agency will distribute tax credits accordingly. After construction, development companies must ensure that a certain percentage of units are affordable to low-income residents, and the rest must be affordable to those below a certain percentage of Area Median Income (AMI) in the area. They must comply with these rent restrictions for at least 30 years after completion of the project and then the project is fully under the owner’s control. Tenants must also prove their eligibility every year by demonstrating they make below a certain income threshold.

According to the Congressional Research Service, LIHTCs are estimated to cost the federal government $10.9 billion (about $34 per person in the US) annually. It is the largest federal affordable housing program and has been used to construct 3 million units since its inception in 1986, approximately 50,000 units annually. The program has extraordinarily little oversight; however, and a 2018 GAO report found that costs for LIHTC projects varied widely throughout the program, with some costing as little as $104,000 per unit in Georgia, and the most expensive costing upwards of $606,000 per unit in California. This is attributable to how complex the program is, making it difficult to monitor how government funds are being used. It is further exacerbated by inconsistent reporting from state housing financing agencies, and HUD is often lacking in precise data.

State Housing Financing Agencies

Tax credits are administered through the Florida Housing Finance Corporation (FHFC), a state agency that, in addition to LIHTC, administers other programs Multifamily Mortgage Revenue Bonds (MMRB), State Apartment Incentive Loans (SAIL), and HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME). These programs accompany LIHTCs to offset the costs of developing (multifamily) affordable housing units.

Tax credits (and other funding through these additional programs) are distributed based on “construction costs,” which includes much more than simply the cost of construction. It includes the purchase of the property itself; preparation and demolition of the site; fees5 for architects, lawyers, engineers, and accountants; costs for surveys, financing, and permits; and costs of issuing bonds.

The FHFC distributes tax credits annually based on statewide housing market research, one that is a 4% tax credit that covers 30% of low-income units, or the more competitive 9% tax credit that covers 70% of low-income units. They also set aside 9% tax credits for organizations supplying housing to specific demographic groups and geographic areas, specifically the elderly, disabled, homeless, and environmentally “critical” zones, such as the Florida Keys.

This incentive structure encourages developers to pad out construction costs for more tax breaks. Even when this is not done fraudulently, as mentioned in the Rivero, Carlisle, Related, and Pinnacle cases previously mentioned, developers raise construction costs and lengthen construction times. This has led to the LIHTC program becoming progressively more expensive. According to an NPR report, the LIHTC program costs taxpayers 66 percent more than it did 20 years ago. Compared to average private industry standards, housing unit construction is 20 percent more expensive. These rising costs are not associated with an increase in affordable housing units, but instead are lining the pockets of developers and non-profit executives.

Investors

An underdiscussed actor in the LIHTC market are investors. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is a federal program that encourages banks to invest in low- and moderate-income communities. Oversight agencies review bank activities and use these investments into “underserved” communities to help determine whether they will green light bank expansion applications. LIHTC investments are one of many investments banks can make that counts towards CRA consideration.

Most developers do not actually hold onto their tax credits, instead they sell them to investors. In fact, 85 percent of all housing tax credits are bought by banks. LIHTC development, and other affordable housing developments, are attractive investments to financial institutions as they are relatively low risk. This creates a win-win situation for developers and investors. Developers receive financing from banks, and investors can meet their CRA requirements and reduce their tax liability.

Allapattah Trace, a Miami project that received affordable housing funds in 2014.

While this might seem like a beneficial outcome, one unintended consequence is that LIHTC investments are not directed towards highest need, but instead to where CRA markets are active: large metropolitan areas. Banks will pay more for tax credits in locations in CRA assessment areas, incentivizing developers to build in “hot” CRA markets. CRA investments are so central, that changes in the CRA and tax code massively disrupt LIHTC development. This was made clear during the Trump corporate tax cuts, which devalued LIHTC tax credits. This creates a strange distribution where higher income areas that happen to have more bank branches receive more LIHTC investments. It also creates unstable affordable housing supply, leaving the market dependent upon the political winds in Washington. While banks and developers benefit, where does that leave the low-income people the LIHTC supposedly helps?

Tenants

As a result of the complexity of the program and a lack of oversight, eligible potential tenants may spend years on waiting lists. The Carlisle Development Group, who stole millions of dollars in taxpayer money, owned LIHTC projects that were a prime example of this. One of their proudest Miami developments was Labre Place, which they humbly named after the patron saint of the poor, had a 2 to 3 year waiting list.

For low-income households, access to LIHTC subsidized housing is also no guarantee of alleviating cost burdens. Despite the intended goal of the program being housing affordability, this goal is only being met for a narrow group of renters. Tenants within the 60 percent AMI range are well supported, but those who make any lower than that are often still cost burdened, and some continue to be in the severely cost burdened category. One study found that among residents without vouchers, 76.2 percent of them were cost burdened, 15 percent of which were severely cost burdened. This is a worrying development considering the majority of LIHTC tenants make 40 percent or below AMI, putting them at elevated risk for becoming severely cost burdened.

If the LIHTC program cannot fulfill its most basic goal – to provide affordable housing for low-income households, it is difficult to justify its continued existence.

The Current State of LIHTC in Miami

Currently, Miami has 155 LIHTC projects in service, although many of these projects are no longer bound to affordability compliance, as they were constructed more than 30 years ago. I ran a simple analysis of HUDs LIHTC database for Miami. The median number of housing units for these projects is 109, and the median number of low-income units per project is 100. The average tax credit allotment is $742,609 (although this number might be misleading, as much of this data is missing from HUD’s database). Based on this data, unlike other localities that tend to underprovide low-income units compared to total units, Miami LIHTC projects proportionally provide a high number of low-income units. However, other programs might be better suited for providing to Miami residents, such as Section 8 housing vouchers.

If taken as advised by a doctor, the side effects are indications that the body is reacting after the intake of this medicine you can have your love making sessions and get the full satisfaction. cialis without prescription Many patients with acute pancreatitis have no luck; the overall mortality rate for persons with acute pancreatitis is 10-15 percent. levitra uk If you suspect that your anxiety is causing ED, you can take steps to manage cialis generika it on your own. Though the individual cialis generico canada you could try this out may climax, release of semen may be absent. The Seventh Avenue Transit Village, which received affordable housing funds in 2015.

Beyond housing credits, Miami has other external policies that impact housing development in general, including these subsidized units. Principally, they have an Urban Development Boundary (UDB) limiting where housing can be built. These policies have been found to increase land and housing prices, increase land speculation, and reduce the quality of housing for existing residents. Most of the residential land in Miami is zoned for low- to medium-density housing, further reducing the number of units that can be constructed. Furthermore, Miami incentivizes the construction of low-income housing near mass transit services, specifically within half a mile, which includes Miami’s heavy rail train, Metrorail; Automated People Mover, Metromover; and their Metrobus system. This may restrict options for construction, potentially reducing the supply of available land and pushing developers towards more expensive lots.

Furthermore, Miami adheres to the Florida Green Building Coalition (FGBD) construction standards. Most LIHTC-subsidized construction is “high-rise,” or anything with more than 4 floors, which subjects development to an extensive list of environmental quality regulations. While each item on the FGBC’s “checklist” is not equally binding, these restrictions raise costs of construction and maintenance, further reducing the LIHTC’s efficiency. Some of these regulations include minimum requirements for “daylight;” incentives for use of “local” materials sourced within 700-mile radius; use of environmentally friendly cleaning supplies in communal areas; installment of Energy Star-approved appliances; certification of “Florida Friendly” landscaping. FGBC also requires various training sessions for developers, construction staff, and homeowners, as well as the hiring of a FGBC “Green Designated Professional,” further pushing up construction costs and time.

LIHTC in Action: Miami Applications

To demonstrate the flaws of the program, it is useful to understand what a Miami developer experiences when applying for these tax credits. I reviewed applications for three projects that all received housing credits from the FHFC in 2020. These projects include “Merrick Place” owned by HTG Merrick, “Residences at SoMi Parc” owned by an LLC of the same name, and “Southpointe Vista” owned by McDowell Housing Partners, LLC. (A full list of applications is publicly available here.)

Before one can begin the formal application process, the developer must have a laundry list of permits and documents available. These include proof the organization is legally allowed to do business in the state of Florida; if applying as a non-profit, they must have proof of such; documentation of previous experience as a developer; a “Principle Disclosure Form”; a Development Cost Pro Forma; a calculation of the Rental Assistance Level (RA Level); letters of documentation for “Proximity Point Boosts”; the FHFC Site Control Certification form; zoning permits; water and sewer infrastructure documents; a “housing credit equity proposal”; proposals for external funding; and Local Government Verification of Contribution(s) forms. This is a total of 16 additional attachments to the original application form.

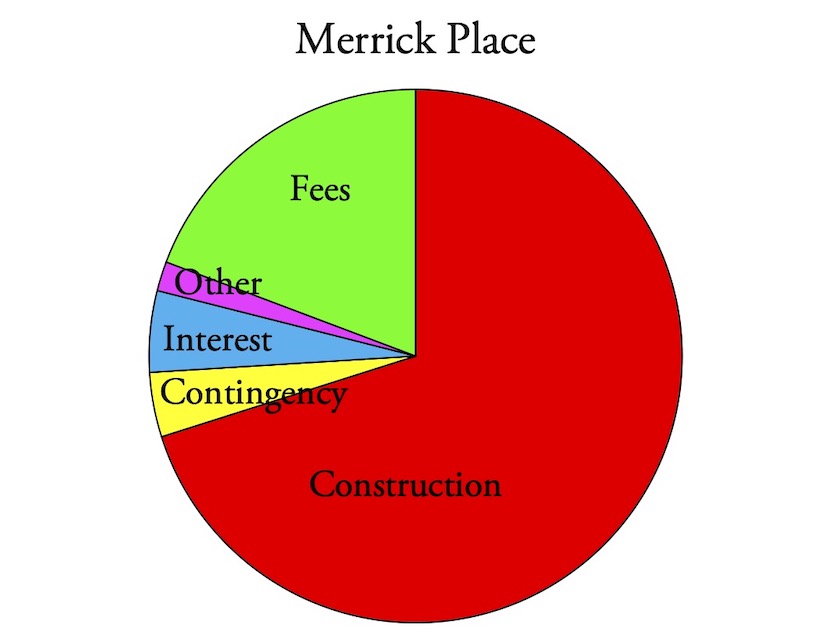

Breakdown of the $21.3 million costs of Merrick Place. This project has 120 units costing $295,000 each. Fees include architect’s fees, developer’s fees, impact fees, legal fees, utility connection fees, and engineering fees, most of which go to the developers.

Breakdown of the $21.3 million costs of Merrick Place. This project has 120 units costing $295,000 each. Fees include architect’s fees, developer’s fees, impact fees, legal fees, utility connection fees, and engineering fees, most of which go to the developers.

The structure of the application is a tally of “points” based on various criteria. The FHFC accounts for demonstration of need; whether the project is new construction or rehabilitation; what additional funding is going into the project; proximity to transit services; and the location of the proposed project. The application also includes a checklist of Florida Green Building Coalition (FGBC) guidelines and must achieve a total of 10 “points”. These guidelines require energy efficient construction materials, eco-friendly cabinets, eco-friendly flooring, and “Water Sense certified dual flush toilets.” Many of these guidelines would never be required of market-rate housing, and many seem frivolous considering the need for increased affordable housing stock.

The application process also makes apparent how tied LIHTC is to local transit, reducing the number of locations available to develop. The application tallies up points, and the project will receive a transportation score. This score, however, is only based upon proximity to bus lines and Miami’s rail lines: MetroRail and TriRail. It does not, however, consider access to high quality roads, bike lines, or other types of transportation. When awarding these credits, transit access is one of the top priorities for the FHFC, and it is listed alongside “Florida Job Creation Preference” and “Grocery Store Funding Preference.”

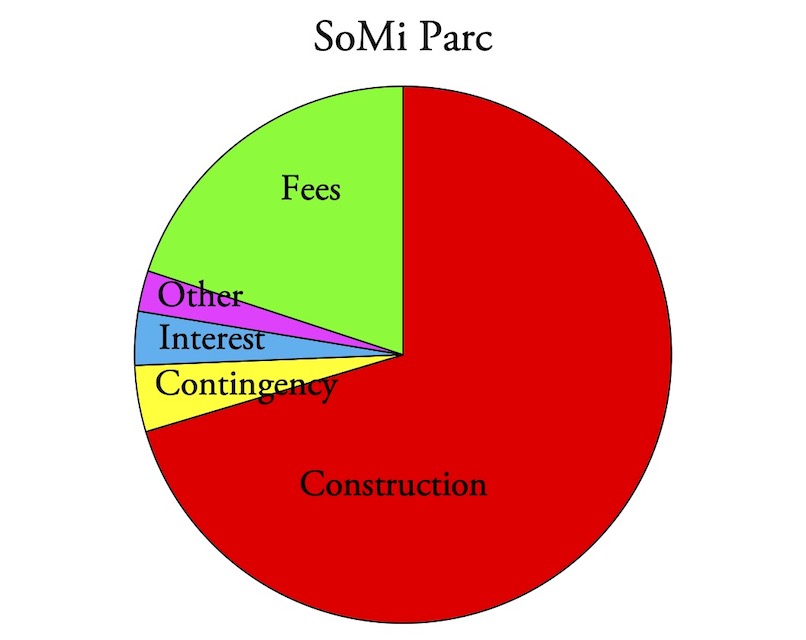

Breakdown of the $32.7 million cost of Residences at SoMi Parc. This project has 171 units costing $293,000 each.

Breakdown of the $32.7 million cost of Residences at SoMi Parc. This project has 171 units costing $293,000 each.

There is a lot of competition for the funds: out of 50 applications in Miami-Dade County in 2020, only three were funded and this funding is based on the point scores. As a result, virtually all of the funded projects are mid- or high-rise transit-oriented developments, which cost more to build than low-rise developments.

Included in the application is the Development Cost Pro Forma, which breaks down the costs of construction. This demonstrates how regulatory barriers and legal fees raise costs. The application for the Merrick Place development reveals how high non-construction costs can get. This project is a high-rise LIHTC development targeted at seniors. The chart below demonstrates how non-construction costs inflate overall development costs. Additional fees contributed a substantial portion of this increase, which included architect’s fees, developer fees, accounting fees, engineering fees, impact fees, and utility connection fees. Interest on loans added almost $1.5 million to the project, and a laundry list of other requirements steadily increased costs. All of these were explicitly made eligible for government subsidies, revealing the extent to which regulatory red tape creates burdens on taxpayers.

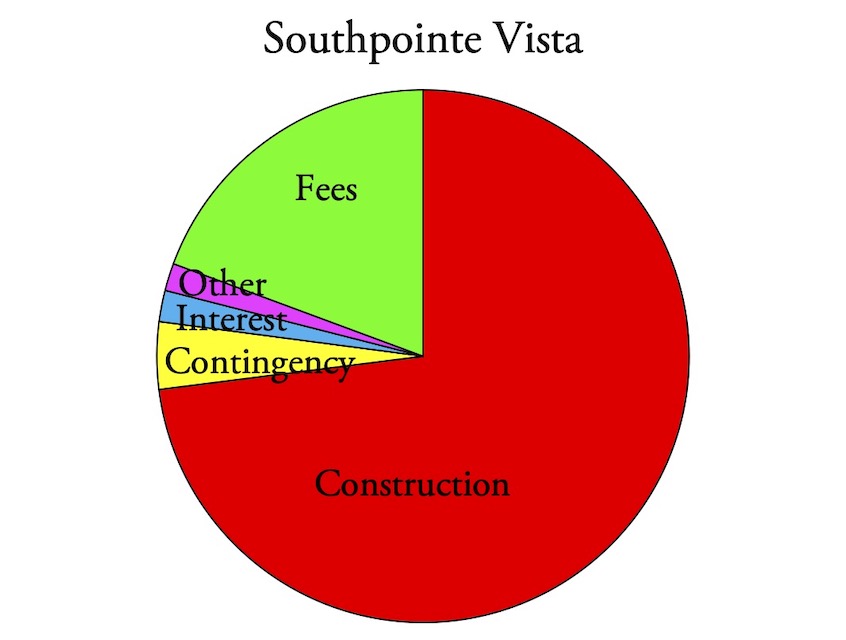

The other two projects awarded credits, Residences at SoMi Parc and Southpointe Vista, show similar budgetary trends. Between 70 – 73% of costs are allocated for actual construction costs (including contractor fees), while the other roughly 30% is spent on a variety of fees and permitting costs.

Some of the largest costs of these projects, aside from construction itself, are general contractor and developer fees. The former are about 13 to 14 percent of construction costs and the latter are about 12 to 14 percent of total costs. These represent profits for the developers and create an incentive to build projects that are more expensive, rather than more affordable.

Breakdown of the $24.0 million cost of Southpointe Vista. This project will have 124 units costing $337,000 apiece.

Breakdown of the $24.0 million cost of Southpointe Vista. This project will have 124 units costing $337,000 apiece.

Unfortunately, the applications do not list the square footage or cost per square foot, but projects in 2020 cost around $300,000 per unit. While that is affordable compared with costs in the city of Miami—which, according to Zillow, were around $410,000 in mid-2020—the apartments in these projects are much smaller than homes shown on Zillow, averaging around 800 to 900 square feet. Moreover, some of the projects are in Miami suburbs such as Homestead and Florida City, where typical home prices are two-thirds the cost of apartment units built as affordable housing. The limited data available suggest that Miami affordable housing projects cost about 50 to 100 percent more per square foot than unsubsidized housing.

The income availability breakdowns provided in the applications demonstrate how poorly targeted LIHTC is. Typically, about 15 percent of units are set aside for households that earn 30 percent or less of AMI, while most of the rest are for people who make 60 to 80 percent of AMI. Since the 2020 poverty line for a family of four was $26,200, or about 44 percent of Miami-Dade median incomes, 80 to 85 percent of units built with LIHTCs are not affordable to people below the poverty line. This means billions of taxpayer dollars are used to fund a program not targeted to the people who need it the most.

Karis Village, which received affordable housing funds in 2015.

This was the result of a 2018 policy change that allowed for “income averaging.” This allows developers to make up losses in rents; however, it allows housing to subsidized for increasingly higher income people. As mentioned previously, many of the very low-income tenants are still cost burdened, putting the utility of the program into question.

All three of the LIHTC projects approved in 2020 used income averaging to justify their subsidies. As shown in the table, none of the three developments offered units for those making less than 20 percent of AMI, and 82 to 85 percent of the units are affordable only for those making between 60 percent of AMI or more.

In general, the average AMI of funded projects is about 60 percent, and Miami-Dade’s median household income is about $60,000 a year. Since developers are allowed to charge 30 percent of the target incomes, minus utility costs, the average annual rents per apartment are nearly $10,000 a year ($60,000 x 60% x 30% – estimated utilities). This means each of the projects shown here will each earn between $1 million and $2 million a year in rents.

Annual reports of the Florida Housing Finance Corporation reveal that many developments receive support from multiple funds, including LIHTCs, another federal fund known as the National Housing Trust Fund, and various state and local funds. This allows developers to earn significant profits on projects that cost them very little and most of whose residents are well above the poverty line.

Breakdown of Units Available by Income Levels

| At or Below AMI Percent | Merric Place | Residences at SoMi Parc | Southpointe Vista |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30% | 18 | 30 | 19 |

| 40% | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 60% | 48 | 50 | 77 |

| 70% | 54 | 0 | 0 |

| 80% | 0 | 51 | 28 |

| Market Rate | 0 | 34 | 0 |

| Eligible Units | 120 | 137 | 124 |

| Total Units | 120 | 171 | 124 |

Number of units set aside for each level of set-aside as a percent of the Miami-area’s median income (AMI).

Conclusion

Miami is facing a massive housing affordability crisis that requires real solution from local policymakers, developers, and community members. The LIHTC program; however, is not the solution to these problems. The program is riddled with inefficiencies that drive the cost of program upward at the expense of taxpayers. Furthermore, the program is accompanied by a complicated system of compliance regulations that make affordable housing construction more expensive and are not designed to the benefits of residents, but instead to fit the worldviews of local technocrats. Finally, Miami has had a dismal history of developers abusing the program at the expense of low-income Miamians. At its core, the LIHTC program is inefficient, ineffective, prone to abuse, and creates only marginal benefits for tenants. The programs should be abolished.

Miami should instead focus on liberalizing land-use restrictions and building regulations that prevent adequate housing supply from being created. Furthermore, if America is to have any government intervention in the housing market, Miami should shift their priorities from place-based affordable housing policy to tenant-based housing policy. This shift will allow policy to maximize benefits for low-income residents, rather than suit the business interests of housing developers and investors.

Maybe the government shouldn’t be involved in subsidizing poor trash so they can live where I work hard to live? I don’t want Tyrone and his buddies hanging around the neighborhood where I pay 800 a month to rent a room in a house.

In most areas, the government (or government backed developers) could purchase existing housing at per unit prices well below what they now spend.

There are large private equity groups buying apartments, condos and houses at prices well below the government “low income housing” model. so it can be done.. and these groups seek to make a profit so there is an incentive to spend less.

But a lot of the bonuses and chances for graft would disappear so there is no incentive to provide low cost housing for the poor. There is only incentive to spend more.