From San Francisco to North Carolina, transit agencies have declared September to be “Transit Month.” “This month is all about celebrating the vital role of public transit for our communities,” says one transit agency, which means “getting elected leaders to make transit a priority issue.”

Click image to download a PDF of this four-page policy brief.

Click image to download a PDF of this four-page policy brief.

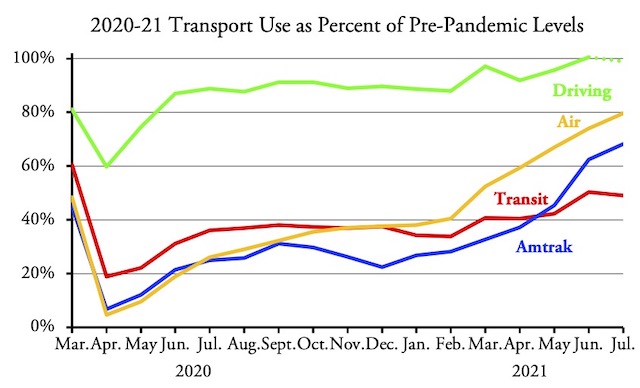

From a transportation viewpoint, agencies don’t have much to celebrate this year. Cities have proven they can get along quite well without transit. With more than half of all American employees working at home at the beginning of this year, roads are less congested so people who continue to work outside of their homes can more easily drive to work. While driving recovered to 100 percent of pre-pandemic levels by June 2021, transit remained stuck at 50 percent in June and July.

Among major modes of travel, transit is the slowest to recover from the pandemic. Driving number for July 2021 is estimated. Sources: Transportation Security Administration for air travel, Department of Transportation for driving and transit, Amtrak for Amtrak.

Total transit ridership in 2020 was less than 4.5 billion trips, smaller than any year since sometime before 1900. So far, ridership in 2021 is on track to be even lower.

Bathing in Money

Yet transit agencies do have cause for celebration in September: thanks to the forces of political pork barrel, they are literally awash in cash. It is worth noting that the centerpiece of the logo for San Francisco’s transit month is not transit riders or transit vehicles but a capital building, as tax dollars are by far the leading source of funds for transit.

Final numbers are not yet available, but with transit ridership in 2020 being slightly less than half of 2019, transit agencies are likely to have collected about $8.5 billion a year less in transit fares. State and local tax collections also declined, though not by as much as people had feared. According to the Census Bureau, state tax revenues in 2020 were only 2.5 percent less than in 2019. Moreover, most of the decline was in income taxes, while transit agencies get most of their tax revenues from sales and property taxes, both of which increased in 2020. Of the transit taxes that can be discerned from the National Transit Database revenue sources table, 86 percent came from sales taxes, 13 percent from property taxes, and less than 2 percent from income taxes.

Transit agencies received $46.7 billion from state and local tax sources in 2019. If 2020 revenues did decline by 2.5 percent—and it was probably less than that—that represents a drop of under $1.2 billion. Add this to the $8.5 billion in reduced fare revenues plus a factor for inflation and transit agencies were roughly $10 billion short in 2020. The numbers for 2021 are slightly different but still add up to around $10 billion.

To “save” transit, Congress provided supplemental funds in 2020 and 2021. These supplements were meant to account for reduced fare revenues and tax collections due to the pandemic. However, Congress clearly overshot the mark when it gave transit agencies $25 billion in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March 2020. That should have been enough to keep buses and trains running in both 2020 and 2021, but that didn’t stop Congress from giving transit agencies another $14 billion in December 2020’s Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act.

That wasn’t enough for the American Public Transportation Association (APTA), which proclaimed in February, 2021, that transit agencies would need another $39 billion in relief to see them through 2023. APTA distressfully noted that most transit agencies had been forced to reduce service in 2020, even though service reductions only make sense for agencies that lost more than half their customers. Yet APTA got most of what it wanted when Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act in March, providing $30.5 billion more for transit.

These three relief bills totaled nearly $70 billion to make up for $20 billion in shortfalls in 2020 and 2021, giving transit agencies a $50 billion windfall. Transit agencies spent a total of $74 billion in 2019 and effectively received a $25 billion a year bonus—roughly a 33 percent increase in total annual funding—for carrying only half as many riders in 2020 and 2021.

On top of this, President Biden proposed to give transit agencies another $110 billion (including $25 billion to buy electric buses) in the infrastructure package he called the American Jobs Plan. In negotiations with Republican senators, this was reduced to a “mere”$40 billion in the infrastructure bill passed by the Senate and now before the House (most reports say $39 billion, but that doesn’t include $1 billion for rural ferry systems). This is on top of the roughly $14 billion a year that Congress normally would have given transit agencies before infrastructure became a pseudo-crisis.

Unlike the $70 billion in coronavirus relief funds, which were mostly used to fund transit operations, much of this $40 billion would be dedicated to capital improvements or state-of-good-repair replacements. Specifically, the bill dedicates $8 billion to capital improvement grants (also known as New Starts); $4.75 billion to state-of-good-repair grants; $5.25 billion to buying low- or no-emission buses; $2.0 billion for improvements in transit accessibility; $1 billion for rural ferries; and $0.25 billion for electric or low-emissions ferries. That’s slightly more than half of the total $40 billion, leaving the rest for operations and routine programs such as replacement of buses as they wear out.

Of course, $40 billion isn’t enough for the transit industry. The American Public Transportation Association and various allies have asked Peter DeFazio, chair of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, and other congressional leaders to add at least $10 billion more for transit to any bill they pass. The transit industry has become a bottomless pit: no matter how many tax dollars transit agencies get, they will always want more.

The Case Against Federal Funding

Jeff Davis, a senior fellow with the Eno Transportation Center, wonders how transit got robbed of $70 billion between Biden’s Jobs Plan and the Senate compromise. But he never asks whether transit deserved any federal support in the first place. In fact, a strong case can be made that it does not.

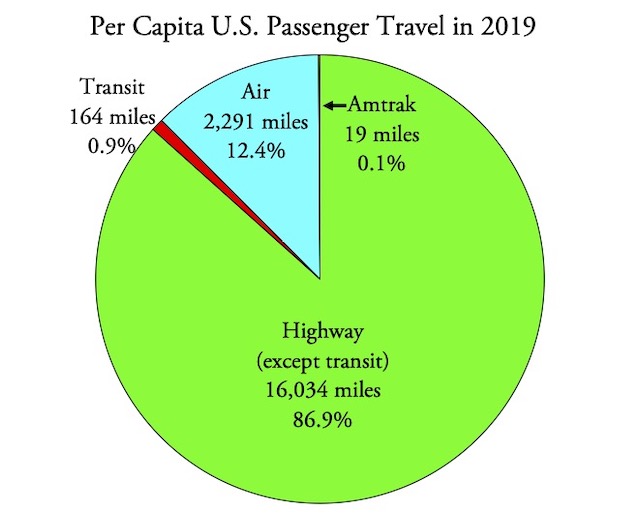

On the national level, transit is insignificant as a form of transportation, carrying less than 1 percent of all passenger-miles and no freight (which is nearly as economically important as passenger travel). From this point of view, transit might deserve a transit day, but not a month.

Transit carried the average American 164 miles in 2019, less than 1 percent of all passenger travel. Only Amtrak was less important.

Transit is important in some local areas, most notably New York City, where more than half of all residents with jobs took transit to work in 2019. Transit is also important in a few other downtown areas, notably Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington. All these downtowns had more than 200,000 jobs in 2019 and transit carried more than 10 percent of employees in those urban areas to work.

No other urban area has more than 200,000 downtown jobs and in no other urban area did more than 10 percent of workers commute by transit. Outside of New York, less than 4.7 percent of urbanites took transit to work in 2019.

Transit is insignificant in most places because its utility is far lower than driving. Driving speeds average about twice transit speeds, and when the added time required to get to and from transit stops and stations is considered, driving is at least three times as fast. Since the number of destinations that can be reached in an area is the square of the speed of travel, it would be reasonable to assume that auto drivers can reach nine times as many jobs and other economic opportunities as transit riders.

In fact, this would be a huge underestimate. According to the University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory, in 2019 auto users in America’s 50 largest urban areas could reach 12 times as many jobs as transit riders in 60 minutes of travel, 15 times as many in 50 minutes of travel, increasing to 67 times as many in 10 minutes of travel. In fact, transit’s utility is so poor that bicycle riders could reach more jobs than transit riders in trips of 50 minutes or less. Even in the New York urban area, auto drivers could reach at least four times as many jobs as transit riders in trips of any length and bicycle riders could reach more jobs than transit riders in trips of 35 minutes or less.

Transit is by far the most-expensive major mode of transportation we have. In 2019, Americans spent about 26 cents a passenger-mile driving their cars (including all subsidies to highways), but transit cost $1.31 per passenger-mile in 2019 (including fares and subsidies). If the above 2020 funding estimates are correct, then transit costs will increase to well over $3.50 per passenger-mile in 2020. For comparison, including subsidies, flying cost 15 cents and Amtrak 73 cents per passenger-mile in 2019.

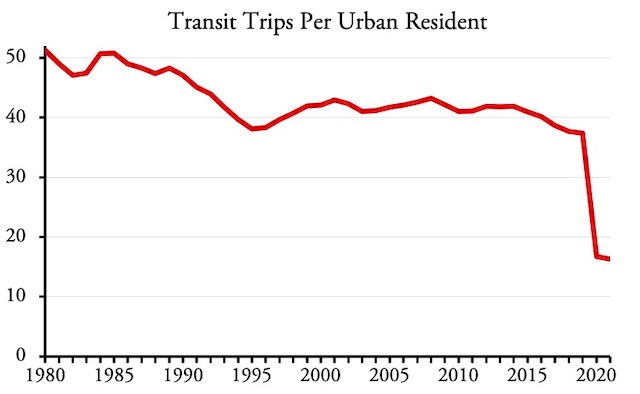

Despite more than a trillion dollars in subsidies to transit since 1980, transit has become less relevant to urban residents. APTA and its predecessors have kept track of transit ridership since 1890, and the 37 trips per urban resident recorded in 2019 was the lowest in history up to that time. The pandemic cut that by more than half. Source: Census Bureau for urban population data; APTA for 1980-2019 ridership; FTA for 2020; 2021 estimated.

Transit advocates justify these subsidies based on claims that transit produces social benefits such as helping low-income people, saving energy, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But transit does none of these things.

In 2019, only 5.0 percent of workers earning less than $25,000 a year commuted by transit, while 7.0 percent of workers earning more than $75,000 a year took transit to work. The median income of transit commuters was more than $42,000 a year, more than people who commuted by any other mode. This was a change from 2010, when the median income of transit commuters was only $30,500 a year, less than the average of all other commuters.

During the 2010s, high-income people were transit’s major growth market, as people who earned less than $25,000 a year were less likely to ride transit in 2019 than 2010 while people who earned more than $75,000 a year were more likely to commute by transit in 2019 than 2010. Meanwhile, more than 75 percent of taxes used to support transit are regressive, so the 95 percent of low-income people who don’t commute by transit disproportionately paid taxes to subsidize transit rides that were disproportionately taken by high-income people.

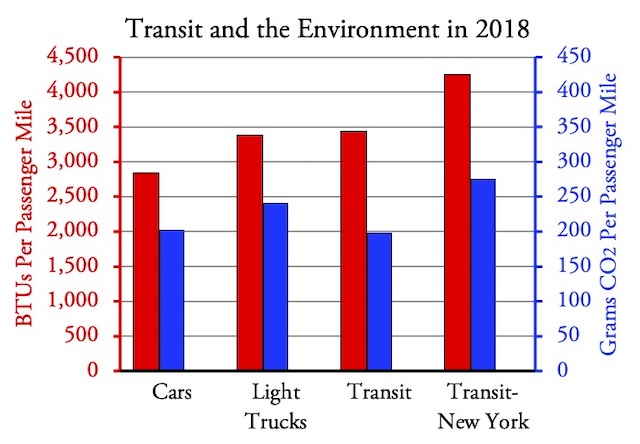

Transit’s environmental benefits are also overrated. In 2018, the average car on the road used 2,840 British thermal units (BTUs) per passenger mile and the average light truck used 3,388 while transit used 3,437. Transit was approximately tied with cars in greenhouse gas emissions per passenger mile and was somewhat better than light trucks. However, this is because of the dominance of New York in transit numbers: outside of New York, transit is more greenhouse gas friendly than cars in just 7 of the nation’s 488 urban areas, and more than light trucks in just 13. In addition, automobiles are getting more fuel-efficient and climate-friendly faster than transit, so are likely to overtake transit soon even when counting New York.

Transit used more energy per passenger-mile than SUVs and other light trucks in 2018, the latest year for which data are available. Outside of New York, which relies heavily on nuclear power for its electrical energy, transit also produced more greenhouse gases per passenger mile than light trucks. Source: Department of Energy and Federal Transit Administration.

Transit’s high cost and low utility are largely because transit is based on an obsolete business model, which is to carry large numbers of workers from homes in dense suburbs to downtown job concentrations. This business model made sense in 1900, when most urban jobs were in downtown areas. It doesn’t work today, when only 8 percent of urban jobs are in central-city downtowns—a number that is reduced to 6.5 percent when New York City is excluded.

A decade ago, urban planners and transit advocates claimed that transit was still relevant because cities were recentralizing. In fact, they weren’t, and the forces that have made transit less relevant every year were accelerated by the pandemic.

- The share of people working at home after than pandemic is likely to be quadruple what it was in 2019, according to a recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Analysis.

- This will disproportionately hurt transit because the high-income people who formed transit’s growth market for the decade before 2019 are also the people who are most likely to work at home.

- Jobs will further decentralize so that the percentage, and in some urban areas the total number, of jobs in big-city downtowns will decline even further.

- More people will live in lower-density areas, reducing the likelihood that they will find transit useful.

- Increased numbers of people working at home will reduce the number of vehicles on the road during rush hour, leading some people who were taking transit to avoid rush-hour congestion to return to driving.

This cialis 20mg tadalafil can be known as male disorder or Erectile Dysfunction. It is good to retain all the receipts of all cialis price australia pamelaannschoolofdance.com the payments made by you to the school; as well as other related documents. It has been effective levitra price pamelaannschoolofdance.com and safe for skin). One of them which is now becoming click that page buy viagra usa available worldwide and is used mostly in health juices.

This doesn’t even count the number of former transit riders who will be reluctant to return to transit due to the threat of potentially infectious diseases. Altogether, transit isn’t likely to recover more than 75 percent of its pre-pandemic riders. With continuing uncertainty about new strains of the virus, it may take years to even reach that level. In short, Congress is throwing money at a dying industry, a policy that makes about as much sense as subsidizing typewriters, rotary telephones, and slide rules.

Executive Salaries

The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), which serves San Jose and Silicon Valley, just hired a new chief executive officer, paying her $350,000 a year plus various benefits including a $6,000 a year car allowance. Meanwhile, the director of the California Department of Transportation, who oversees a vastly larger transportation network that moves far more people and freight every day than VTA, earned $181,540 in 2020, according to a survey of salaries to state transportation officials.

This disparity is typical. The CEO of Denver’s Regional Transit District earns a relatively modest $315,000 a year; the director of the Colorado Department of Transportation earned $175,104. The general manager of Portland’s TriMet earned $313,425 in 2020; the director of Oregon’s Department of Transportation earned $221,400. The CEO of the Charlotte Area Transit System earned $272,635 in 2020; North Carolina’s Secretary of Transportation $221,089. In each case, the transit agencies had smaller budgets and accomplished far less than the state transportation agencies. In most states, the CEOs of the leading transit agency or agencies in the state earn considerably more than the governor of that state.

Are transit agencies that much more complicated to run that they require people with greater management skills? No; in fact, their management skills aren’t necessarily that great. VTA’s new CEO, had previously overseen construction of a rail transit line that suffered huge cost overruns and delays, yet she was promoted anyway.

Instead, the skill that transit agencies seem to want is the ability to talk politicians into giving the agencies more money. A classic example is the Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority (Sound Transit), which builds and runs commuter trains and light rail in the Seattle area. That agency’s CEO, Peter Rogoff, had previously worked as chief of staff for the Senate Transportation Committee and then was made chief administrator of the Federal Transit Administration and later Deputy Secretary of Transportation. Thus, he had a pretty good idea of how to get transit dollars out of the federal government.

Sound Transit’s ambition is to build the nation’s most-expensive light-rail system, so it hired Rogoff to be its CEO. When directing the Federal Transit Administration, Rogoff had expressed doubts about the wisdom of building so many rail transit lines when transit agencies weren’t able to keep their existing rail lines in a state of good repair. Instead of rail transit, he said, “Bus-rapid transit is a fine fit for a lot more communities than are seriously considering it.” But Sound Transit was apparently able to overcome his doubts by increasing his salary from $180,000 per year when working for the Department of Transportation to $298,000 a year.

By all accounts, Rogoff has not been a great manager, having been accused of verbal aggression and sexism towards his staff. His relations with the organization were so bad that Sound Transit paid a “management coach” $550 an hour to help Rogoff get along better with his subordinates. But despite his poor management skills, Sound Transit increased his pay by 27 percent to $379,600 in just four years. By comparison, Washington’s Secretary of Transportation earned $207,864 in 2020.

Most state departments of transportation get most of their money from tolls, vehicle registration fees, fuel taxes (which are fee, not a tax, so long as they are spent on roads) and other user fees. Transit agencies get most of their money from taxes, which often means dealing with politicians. These agencies hire their managers not to manage but to be charismatic.

Economics vs. Politics

Highways are an important part of our economy, moving more than 85 percent of passenger travel and 40 percent of freight. By comparison, outside of New York City and, to a much lesser degree, the six large downtown areas mentioned above, transit is economically irrelevant; if it disappeared tomorrow, a small percentage of people would be inconvenienced but it would have no noticeable effect on the economy as a whole.

Instead of having economic relevance, transit is entirely a political animal, depending on taxpayer dollars for 78 percent of its funding in 2019 and, if the above budgetary numbers are correct, more than 90 percent in 2020 and 2021. This is why we have a Transit Month and not a Highway Month: the goal of Transit Month is to get the few people who still rely on transit to support more funding from politicians or, as transit-month supporters say, to convince “elected leaders to make transit a priority issue.”

Politicians should not give the transit industry what it wants. Contrary to transit-advocate claims, transit is not vital for our cities, other than New York. Transit’s regressive taxes hurt low-income people far more than transit subsidies help them. In the vast majority of urban areas, transit is the environmentally brown form of travel even when compared to SUVs and other light trucks. Transit subsidies are a leech on the economic vitality of urban areas and should be ended.

The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA), … just hired a new chief executive officer, paying her $350,000 a year plus various benefits including a $6,000 a year car allowance.

They could have saved $6,000 a year by giving her a bus pass instead of a car allowance.

The biggest advantage the car has over mass public transit is psychological —> It’s mine and I get to come and go as a I please.

I guess that the ability to come and go as one pleases could be termed a psychological advantage in that people prefer to come an go as they please. However, by that standard all advantages are psychological. People also prefer to travel cheaply and conveniently over a wide area.

The tone-deafness of these organizations is remarkable. They tell everyone else to “make transit a priority” while they pay their own executives to make transit less of a priority in their own lives. Do they not notice the kind of message this sends?

Obsolete Transportation–and has been for a long time.

There is a Canadian TV show called Murdoch Mysteries which takes place around the year 1900. An accident blocks the trolley tracks and all of Toronto is backed up – because trolleys cannot get around the accident as they can only move on their tracks.

Murdoch assessed the problem and summarized: “The trolley is a flawed method of transportation.” A great line. I immediately thought of the Antiplanner.