Last Friday, the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, which keeps track of all kinds of transportation, released 2020 data on government revenues and expenditures in transportation. The new data, however, are based on a radically altered definition of revenues and should be rejected.

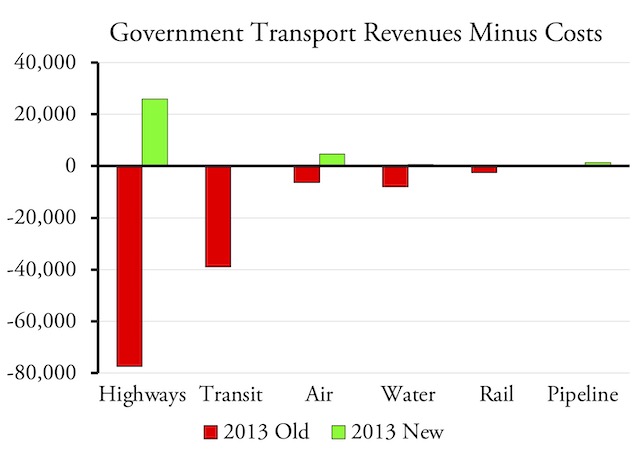

Under the Bureau of Transportation Statistics’ new definition of revenues, transit revenues more than tripled and highway revenues nearly doubled.

The agency has kept track of this information for many years, with revenues being recorded in table 3-32 and expenditures in table 3-35 of an annual report called National Transportation Statistics. In the latest tables, the numbers go back to 2007, but in earlier editions (such as the 1995 edition), they go back as far as 1980 (in five-year intervals).

In all those years, it has been clear that government revenues refers to user fees, including highway fuel taxes, tolls, transit fares, airport landing and airline ticket fees, and so forth. Subtracting government expenditures from these user fees reveals the total subsidies to each mode of transportation.

Under the Bureau of Transportation Statistics’ new definition of revenues, U.S. governments collectively went from losing money to earning profits on all forms of transportation.

Until now. With the 2020 data, the bureau has redefined “revenues.” This can be seen by comparing 2013 revenues in the most recent National Transportation Statistics with 2013 revenues in the recently released data (which include 2007 and 2013 numbers as well 2020 numbers). Voila! Suddenly, all forms of transportation, all of which lost money under the old definition, earned a profit under the new definition. It doesn’t show in the above chart, but transit agencies supposedly earned $44 million in profits.

What magic made such unprofitable operations now turn a profit? Under the new definition, revenues now include “funds collected from non-transportation-related activities but dedicated to support transportation programs, e.g., receipts received by state and local governments from sales or property taxes.”

The key word here is dedicated. If a state legislature appropriates 10 percent of state sales tax collections to transportation, that’s not dedicated and isn’t a transportation revenue. If, however, the same legislature directs that, in the future, 10 percent of state sales tax collections will automatically go to transportation, that’s dedicated and therefore is transportation revenue.

From the taxpayers’ viewpoint, the distinction between appropriated and dedicated is meaningless. The same amount of money flows out of their pockets and into some faceless bureaucracy.

From the users’ viewpoint, the difference between true user fees and dedicated taxes is huge. User fees force businesses, whether private or state-owned, to be responsive to user needs. Dedicated taxes allow those businesses to ignore users and just do what they want.

From the bureaucrats point of view, the distinction between appropriations and dedicated taxes is also real. If the funds are appropriated, agencies have to make the case for those funds every year, which can be really annoying especially if the agency suffers from huge cost overruns and declining patronage. If they are dedicated, the taxes become free money that the agencies can do whatever they want with and no longer have to be beholden to either their customers or to politicians.

If anything, then, dedicated funds are worse than appropriated funds because they take away incentives for transportation agencies to be responsive to either users or voters. I prefer that transportation be funded exclusively out of user fees, but given a choice, I would take appropriated funds over dedicated funds because the former at least gives voters a chance to evaluate how well the funds are being spent.

By counting dedicated funds as transportation revenues, the Bureau of Transportation Statistics is perpetuating a lie that certain kinds of taxes don’t count as subsidies. This is similar to Amtrak saying that tax funds given by state legislatures to Amtrak to run trains in those states are “passenger revenues” in the same sense that Penn State chartering a train to the Rose Bowl would be passenger revenues.

I can’t help but notice that the president when the Bureau of Transportation Statistics made this change is a Democrat. The last time a Democrat was in the White House, the Department of Transportation made other changes in statistical definitions that were similarly questionable, changes that were reversed when a Republican took over the White House.

With respect to highways and transit, the data underlying the Bureau of Transportation Statistics data are readily available in Highway Statistics and the National Transit Database. I’m not as familiar with the sources of airline, pipeline, and railroad data, but it should be possible to fix all the data in table 3-32 if the bureau insists on using its new definition in the future.

Still, I won’t be surprised if we start seeing press reports claiming that highways, transit, and other modes of transport are now earning profits for the government, just as we saw press reports saying that Amtrak lost only $29.8 million in 2019 when actually it lost well over a billion dollars. Sadly, many journalists are easily baffled by bureaucrats as they take it on faith that government employees are always working in the public interest.

so there shouldnt be any potholes anywhere?