In recognition of the fiftieth anniversary of the Edsel, Time magazine has published its list of the 50 worst cars of all time. I usually ignore such lists, because the main reason commercial sites like Time put them on the web — with only one entry per web page — is to get you to click on as many of their web pages (and view as many annoying ads) as possible.

A commercial success but a marketing failure.

This list, however, earned Time a lot of mouse clicks from me after I found the second car on the chronological list was the Model T Ford — probably the most important car ever made. The Model T made Henry Ford a billionaire and allowed him to double worker pay — an action that reverberated throughout the economy. The Model T’s low cost brought mobility to the masses and made a huge contribution to the economic growth of the United States in the first half of the twentieth century. Largely because of the Model T, Time‘s sister magazine, Fortune, named Henry Ford the “businessman of the 20th century.”

So why did Dan McNeil, a Pulitzer-prize winning auto critic, put the Model T on his list? What were his criteria for putting any car on the list?

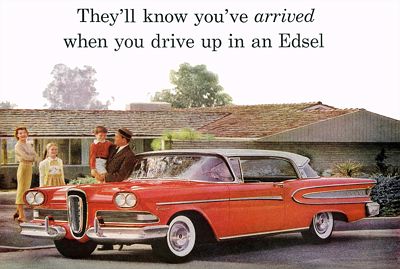

The car that inspired the list, Ford’s Edsel, “wasn’t that bad a car,” says McNeil. In fact, it sold reasonably well, being the second-largest car launch for any brand up to that time. But sales were below expectations — mainly because it was introduced at the beginning of a recession — and so it has become the image of failure.

Another marketing failure on the list is the 1934 Chrysler Airflow, which introduced streamlining before Americans were ready for it. The Airflow was a highly influential car — almost all cars produced from the late 1930s through the early 1950s owe an aesthetic debt to it — but it sold poorly.

So is being a marketing failure Time‘s criteria for “worst car”? Hardly. Many of the cars on the list were spectacularly successful. For example, Chevrolet sold well over a million Corvairs and McNeil admits that “my family had a Corvair, white with red interior, and we loved it.” But the rear-wheel-drive Corvair — GM’s effort to compete against the Volkswagon beetle — turned out to be dangerous to drive, with a tendancy to spin out and to fill the passenger compartment with carbon monoxide when the heater was on. Ralph Nader’s book, Unsafe at any Speed, destroyed the Corvair’s image as a lovable car.

Similarly, the highly successful (more than 2 million sold) Pinto is on the list because of its exploding gas tanks. Only a couple of dozen accidents involved such explosions, so the Pinto was in fact as safe as any other car on the road (and safer than some imports) — but those few accidents gave it a bad image. So that suggests that McNair puts a car on his “worst” list if it is a marketing failure or if its initial success is later marred for safety or other reasons.

Some cars, such as the Yugo and Trabent, are on the list because they were mechanically bad. No quarrel here.

Other cars are on the list, such as the Dymaxian and Aeromobile, because they were experiments that failed. But what is wrong with that? Experimentation is key to any industry, and by definition not all experiments will succeed. These experiments, at least, did not cost a lot of people a lot of money since they were mostly built by tinkerers or funded by a few investors.

Still others, such as the AMC Gremlin and Pontiac Aztek, are included because they are ugly. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and the Gremlin, at least, sold more than two-thirds of a million copies, which was pretty good for a second-tier car company. But if you want to put a car on the list because it is ugly, I can live with that.

So why is the Ford Explorer on this list? A tremendous marketing and mechanical success, fairly safe and not particularly ugly, McNair considers it one of the 50 worst because it “is responsible for setting this country on the spiral of vehicular obesity that we are still contending with today.” Minivans would do most of what an Explorer does better, he says, but people preferred the Explorer’s “outdoorsy” image. He doesn’t consider the possibility that people would rather buy one car that can do many things than have separate cars for each individual use.

Beyond that, what is wrong with an outdoorsy image? Who is McNair or anyone to criticize if someone is willing to pay a little more (or maybe even no more) to get a car (or house or clothes or anything) that projects an image they like? Ford made a car to compete with Jeep, and ended up being very successful because it was a product that people wanted. As McNeil himself notes, when Ford tried to make a bigger SUV, the Excursion, it sold poorly, which kind of blows his “vehicular obesity” argument out of the water.

McNeil also criticizes the Hummer 2 for “putting out all the wrong signals” so soon after 9/11. The Hummer 2’s dirty secret is that it is really not much more than a Chevrolet Tahoe with a different body. The Hummer 2 is a gas guzzler, and for that, McNeil gleefully notes, a “Hummer dealership was torched in Southern California” by “green-niks” — as if the actions of vandals and criminals can reflect on the victims.

McNeil himself is no green-nik. He criticizes the Renault Dauphine, the 1980 Corvette “California”, and the Plymouth Prowler, among others, for being underpowered. If only they had bigger, more gas-guzzling engines, they would have met his approval.

Probably the most important car in history.

Flickr photo from collection of Roadside Pictures

So why did McNeil put the Model T on his list? As McNeil admits, the Model T “put America on wheels, supercharged the nation’s economy and transformed the landscape.” But, he adds, “that’s just the problem, isn’t it? . . . . A century later, the consequences of putting every living soul on gas-powered wheels are piling up, from the air over our cities to the sand under our soldiers’ boots.” But the air in our cities is clean (and our cities are a lot cleaner than if everyone got around on horseback and with horse-drawn cart), while the sand under our soldiers’ boots has far more to do with Israel, and the egos of some of our leaders, than with oil and gas.

The one consistent thing in McNeil’s ratings is image. The Edsel is the prototypical worst-car because it was bad for Ford’s image that it didn’t sell as well as expected. The Corvair and Pinto were bad because they also ended up being bad for their manufacturers’ image.

More than the manufacturers, McNeil is concerned about the image of the people who drive and buy the cars — and he doesn’t mind projecting his political viewpoint into those images. You shouldn’t project a “militaristic” image (as the Hummer 2 does) after your country has suffered an unprovoked attack by terrorists. (Would it be okay after Pearl Harbor?) You shouldn’t project an “outdoorsy” image if all you are doing is taking your kids to soccar practice.

McNeil’s idea of the proper image is highly elitist. McNeil doesn’t have any problem with people driving around in expensive, gas-guzzling s and Maseratis if they have the money to afford them — he only criticizes these cars if they are poorly built.

McNeil’s elitism shows when he expresses more concern for Cadillac owners “insulted” by the production of a poor design of their brand than he has for low- and moderate-income people who just want a basic car and aren’t worried about the image it represents.

For example, the Chevy Chevette makes it onto McNeil’s list of the worst cars even though he admits that he himself is a fan who drove one “across the country three times and it never failed.” So why does the Chevette make the list? Because, having sold in the same price range as the mechanically deficient Yugo, it projects the image of being a poor-person’s car.

Ultimately, this elitist view is the primary objection to both the Model T and Ford Explorer. The Model T provided mobility for the masses. This devalued the mobility that was once reserved for the wealthy elite. The Explorer projected an outdoorsy image (remember the Eddie Bauer edition with Firestone Wilderness tires?), but was resented by Sierra Club-types who wanted people to know that only an elite few could truly handle being in the wilderness.

I plan to say more about such elitist attitudes in a future post. For now, suffice to say that any list that includes the Model T as one of the 50 worst cars in history makes my list of one of the worst lists in history.

It seems you and McNeil have both misunderstood the term vehicular obesity. As with human obesity, where the problem is too much weight for one’s height, vehicular obesity refers to too much weight for the vehicles wheelbase. This is particularly important for safety. Normally as wheelbase and weight increase the safety of that vehicle’s own occupants also increases, by the same amount that the safety of other vehicle’s occupants decreases. The nett effect in multi vehicle crashes is neutral but in single vehicle crashes the effect is positive. Thus if average weight increases so will average safety.

The DOT’s fleet compatability studies have shown this to be generally true for driver deaths per 1,000 pdo crashes, for both cars and LTVs when measured seperately. ie as they get longer and heavier they get safer. But when the types of vehicle were matched on wheelbase it was found that LTVs killed their own drivers at the same rates as one-size smaller cars and killed other drivers at the rate of one-size bigger cars. In essence the added lbs per inch of an SUV compared with a same wheelbase car is a killer, just like human obesity. While the Law of Conservation of Momentum does say that heavier is safer, it also says that softer is safer. That just happens to be the exact opposite of popular opinion (built like a tank = safe).

I don’t think McNeil was particularly interested in safety when he was bemoaning the harbinger of the SUV era.

Mostly what the Explorer did was make station wagons acceptable to baby boomers. People grew to like being “up high” and, with all the SUV’s and increasing numbers of light and heavy trucks surrounding them, a test drive in a regular car made them want another SUV.

I drive a very small and low car and it is like being a fly in a cattle yard when on the freeway. In the pre-Explorer days driving a small sports car never felt uncomfortable or scary like it does today.

It is difficult to discern the author’s selection criteria – too successful in the marketplace, not successful in the marketplace, ugly (to him), unsafe, worse in some way than previous models by the same manufacturer, etc. My criteria would have been different.

I would have put Toyopet (by Toyota) on my list, plus Kia, The GM diesel Oldsmobile and Cadillac models and the VW Rabbit Diesel. Some of the Rabbits would suck crankcase oil and keep running after they were turned off.

He didn’t mention that the early Chevettes had 40,000 mile engines.

Some on the list were legally motorcycles – cars have to have four wheels on the ground.