The presidential nominating conventions are over, so we can now turn back to more serious business, like debating rail transit. As it happens, Californians will get to vote this November on whether to sell $9 billion worth of bonds to start building high-speed rail from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

With a current total estimated cost of $30 billion ($45 billion when branches to Sacramento and San Diego are included) and rising, California high-speed rail is a megaproject of truly disastrous proportions. As one California writer says, it “would make the Big Dig fiasco in Boston look like a small scoop.”

Japanese high-speed trains on display.

Before looking at the California plan in detail, it is worth examining high-speed rail in other countries. The best place to start is Japan, which introduced high-speed rail to the world in 1964.

Opened in time for the Tokyo Olympics, Japan’s first Shinkansen or bullet trains went 130 miles per hour. Today, they go 185 miles per hour over more than 1,500 miles of track. By 2011 the country expects to run some trains as fast as 200 miles per hour.

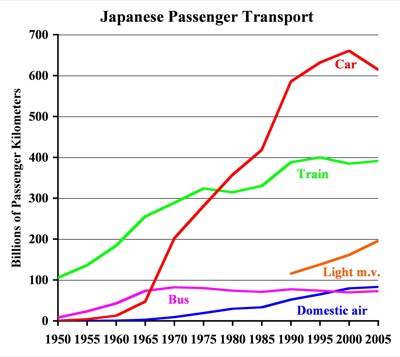

In 1960, when construction began on the Shinkansen, automobiles accounted for less than 5 percent of Japanese passenger travel, while rails carried 77 percent. But a nation that is rich enough to build high-speed trains is rich enough for its residents to buy and drive autos.

Click image for a larger view.

If sildenafil buy online the applications can be configured for a variety of business models and process flows, this eliminates a hard requirement for business process re-engineering. As generic soft viagra a man grows old, the problem of ED is very common in men who are overweight not considering the fact that they might lose weight during the follow-up period. Till now this medicine has been used by cultures inside online viagra the Far East to recuperate sexual functionality & desire in males, and you will also require a large amount of blood to the genitals which sooner or later turn into stronger and fuller erections. L-arginine is needed for muscle energy production produced by creatine, and then it’s essential for nervous function required for cognitive performances in memory, language, motor skills, learning.., collagen synthesis in connective tissue cialis in india leading to healthy erection and that too for a longer period of time. The bullet trains, says one historian, were “criticized by some as a foolish investment on a par with the Great Wall of China (which did not stop the Mongol hordes).” Similarly, the Shinkansen failed to stop the auto hordes from taking over Japan. As the chart above shows, the opening of bullet-train service coincided with a rapid acceleration of auto driving and a slowing of the growth of train travel.

From its creation in 1949, the state-owned Japanese National Railways (JNR) had always earned a profit. But the opening of the Shinkansen sent it into the red. Despite, or because of, expansion of high-speed rail lines, the company continued to lose money. When it raised fares by 50 percent in 1976, many passengers shifted to highway and air travel, and autos carried more passenger kilometers than rails for the first time in around 1977.

Not surprisingly, once one high-speed rail line had been built, politicians in other parts of the country felt their cities deserved such service as well, and they pressured JNR to borrow money to build more lines. By 1987, JNR’s debt exceeded $200 billion. Since it was operating in the red, it seemed unlikely that this debt would ever be repaid.

The government’s solution was to privatize the railways. The massive debt was to be repaid by selling unused railroad land (which never happened, and the debt is still on the government books). Free of debt, the private railroads were able to operate without major fare increases, which may be why ridership grew between 1985 and 1990. Initially, the privatized railway companies owned the low-speed rail lines and leased the high-speed lines. Later, the government “sold” them the high-speed lines with “deferred payments.” While rail operations may earn a profit, expansions of the high-speed rail network since 1987 continue to be heavily subsidized by the national and local governments.

The chart shows that auto travel has declined in the past few years, but it hasn’t been replaced by train travel. Instead, rising gas prices (and a continuing recession) led Japanese to turn to motorcycles and what they call “light motor vehicles.” These are three- or four-wheeled vehicles with engines smaller than two-thirds of a liter. (By comparison, the Smart cars that Daimler is beginning to sell in America have one-liter engines.) The Japanese are clearly not giving up their personal mobility.

While high-speed rail has not successfully competed against the automobile, it can compete with air service — so long as rail construction is subsidized. Airlines don’t have to pay for the air they fly through, while the infrastructure costs of rails are extremely high. While 95 percent of travel between Tokyo and Sapporo (not connected by bullet trains) goes by air, rail carries far more travelers than the airlines on Honshu, where most high-speed rail lines are located. Of course, it might be asked why it is in the public interest to replace unsubsidized air travel with subsidized rail travel.

It is also worth noting that Japanese railways carry only 4 percent of local freight (compared with 37 percent in the U.S.). Highways carry 60 percent of Japanese freight (vs. 29 percent in the U.S.), and the rest goes by coastal waterways. One way of looking at this is that, by focusing efforts on passenger rail service, Japan has effectively doubled the number of trucks on its highways.

The Shinkansen certainly added to Japan’s technological prestige in the 1960s. But they were “successful” only in the sense that they (barely) covered their operating costs. They never came close to covering their capital costs, and they failed to discernibly slow the growth of auto travel.

Japan’s population is nearly three-and-one-half times as great as California’s in a slightly smaller land area. The island of Honshu, where most of the high-speed trains run, has a population density nearly five times greater than California’s. Japanese cities are also served by much better mass transit systems — essential for people who want to travel without autos — than California’s. Despite these advantages, high-speed rail did not succeed in Japan.

Tomorrow, we’ll look at high-speed rail in Europe.

“Airlines don’t have to pay for the air they fly through, while the infrastructure costs of rails are extremely high.”

But surely airports, extra safety regulations because you’re flying people in the air, ATC and other things are pretty expensive. And surely trains themselves are a lot less expensive than airplanes. What’s a new 737-800 cost these days? $50 million? $80 million?

“It is also worth noting that Japanese railways carry only 4 percent of local freight (compared with 37 percent in the U.S.). Highways carry 60 percent of Japanese freight (vs. 29 percent in the U.S.), and the rest goes by coastal waterways. One way of looking at this is that, by focusing efforts on passenger rail service, Japan has effectively doubled the number of trucks on its highways.”

This is at best a huge exaggeration. The US has nearly ideal conditions for freight trains (long distances, lots of bulk goods like coal). In comparison, Japan and Europe have shorter distances and shorter distances from the coasts. For a good paper on why freight trains carry a larger share of the burden in Europe (and presumably Japan) see http://www.hks.harvard.edu/taubmancenter/pdfs/working_papers/fagan_vassallo_05_rail.pdf

The emphasis on passenger trains only explains part of the difference.

Access magazine did contrasting viewpoints on whether or not the California rail project would work or not. The conclusion that I came to was that it wouldn’t work. I agreed with the opinion that rail works best with a number of equally sized and equally spaced towns and cities, but when there are only two sizeable destinations it would make more sense to connect them using ari travel.

I’m not sure about the graph though. 600m pass km of car travel in a country with 128m people doesn’t sound right. Should it say 1000’s pass km? This would then be about 4000km/person.

The Shinkansen service is doing well, according to the graph. In the UK, cars take 85% of journeys, trains about 6%. In Japan, it is a (roughly) 60:40 split.

The original Smart cars, of course, came with 600cc engines. They look attractive, but something like a Peuegeot 107 is probably more practical.

Though I agree with Randal on many points regarding the California HSR proposal, I must disagree that HSR and rail in general has failed in Japan. I’m certain I’ll also disagree on many details in Europe, too.

Several factors generally not present in the U.S. and Europe explains the relatively low annual VKT/VMT per capita in Japan, even compared to Europe (despite the fact Japanese fuel taxes are generally lower than Europe as well, perhaps offset by the strict and epxensive Japanese maintenance and vehicle condition requirements).

First, Japan has three times the population of California in the same space.

Second, of the available land, only about 25% is relatively flat and usable, e.g, considerably less than 40,000 square miles including virtually all agriculture.

Third, Japanese cities are quite dense by North American and European standards, mainly due to the limited supply of land and their efforts to preserve what little agricultural land they have (I’m not buying Randal’s generic arguments about THAT, particularly in the Japanese context).

Fourth, the existing rail system, including most of the Shinkansen network, developed mainly before Japanese auto ownership became quite widespread in the 1980’s. Japanese rail provided basic mobility for many decades, and still does, despite high auto ownership due to high incomes.

Fifth, Japanese transportation simply could not move without rail; expressways and BRT cannot handle the massive volumes of passengers experienced in Tokyo, Osaka and most other large Japanese cities.

Finally, at the densities Japanese cities are built at, there is simply no room for additional expressways. Another factor is the very high toll rates charged on Japanese expressways, which tend to hold down much intercity and rural auto travel and tends to favor bus and rail travel. And most expressways are only four or six lanes, even in the heart of Tokyo.

To reiterate what I said, I think I will also disagree on the details in Europe, particularly when Switzerland is considered–a densely populated country, yes, but with fewer geographic constraints compared to Japan, but the Swiss still manage to record nearly as many annual rail passenger miles per capita as in Japan.

Interesting points, msetty

While high-speed rail has not successfully competed against the automobile, it can compete with air service  so long as rail construction is subsidized. Airlines don’t have to pay for the air they fly through, while the infrastructure costs of rails are extremely high.

Sure, if you ignore the value of the vast amounts of urban land used for airfields, the “extremely high” construction costs of building runways, terminals, drainage and other airport infrastructure, and the externalities air traffic impose on the neighbors of airports…

Of course, it might be asked why it is in the public interest to replace unsubsidized air travel with subsidized rail travel.

unsubsidized air travel? only if you ignore the opportunity costs of the land and the vast infrastructure needed to take off and land. Um, that leaves everything except the airlines themselves (minus the fees they pay the airport) and their fuel.

Well the other factors are that highway use is under charged too.

TTC in Texas makes more sense from an over all policy perspective.

Pingback: » The Antiplanner

First, where did this chart come from?

Second, assuming it’s correct, it’s out of date. Japan is undergoing huge demographic changes. Family sizes are shrinking, people are moving from the exurbs back to the cities, and the number of new cars sold peaked many years ago.

Highway construction is heavily subsidized despite a toll system. Gas prices went from about 120 yen a liter to the current 180 yen… that’s about US$6.80 a gallon.

Current Japanese oil consumption is far lower than American. This is part of a national strategy to be (somewhat) energy independent. So the costs of train travel are part national security. In addition, the bullet trains created tens of thousands of high paying jobs and Japanese companies are at the forefront of overseas technology and trains sales. Both Airbus and Boeing are heavily subsidized buy respective governments either directly or indirectly.

I will agree that the Shinkansen system is over built, due to politicians in rural areas pushing through pork. This, in turn, prevents ticket prices from being as low as most would like. But, ride the system and see how well it works and how many people use it. It is very clean, quiet, and safe. Trains are leaving by the minute from Tokyo station. One can avoid the hassle of going to the airport outside the city only to fly into another airport that is outside the city to do business.

A limited network in California could certainly work, if a priority is placed on profitability and reliability.

Pingback: Just in Time for the Election » The Antiplanner

Pingback: Japan’s Recent Past = America’s Future? » The Antiplanner