For part I, see James J. Hill, Entrepreneur

By 1900, James J. Hill was recognized as a miracle man who would soon be known far and wide as “the Empire Builder.” He helped J.P. Morgan reorganize the Northern Pacific, something he could have done without Morgan’s help except for a Minnesota anti-monopoly law forbidding one railroad from taking over a competitor. He then negotiated the purchase of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, which connected the GN and NP with Chicago and also extended to Denver, Kansas City, and St. Louis. A fleet of steamships extended his reach west to Tokyo, south to San Francisco, and east to Buffalo.

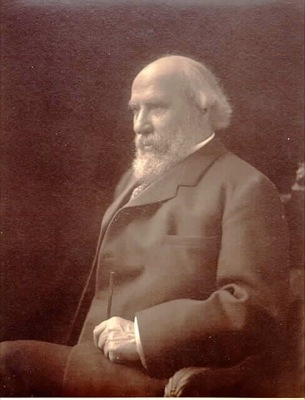

Probably the most famous photo of Hill, circa 1902. Could that be a Thoreau pencil in his hand?

Probably the most famous photo of Hill, circa 1902. Could that be a Thoreau pencil in his hand?

In 1901, Hill had the fight of his life when Wall Street financier Edward Harriman, who had reorganized the bankrupt Union Pacific and purchased the Southern Pacific, tried to take control of the Northern Pacific. Harriman’s real objective was the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, which would provide the UP and SP with access to Chicago. However, he had been unwilling to pay the $200 per share demanded by the company’s president, Charles Perkins. When Hill paid Perkins’ price, Harriman tried to get a share by taking over the NP.

Normally, it is possible to control a company without owning a majority of the stock. Most of Hill’s wealth was tied up in Great Northern stock, and he did not have the resources to get into a bidding war for NP stock. Harriman made his move when J.P. Morgan, who did have the resources, was vacationing in Europe. When the price of NP stock started rising, Morgan’s lieutenants actually started selling stock to take advantage of the higher prices.

Hill got wind of Harriman’s activities and rushed on a train to New York, where he was met by Jacob Schiff, Harriman’s banker. Schiff escorted him to Harriman’s offices and made an offer: between Harriman’s and Hill’s stock, they owned a majority of the Northern Pacific. If Hill would join Harriman (i.e. dump Morgan), together they would control almost every western railway. Respecting Hill’s managerial skills, they offered to give Hill day-to-day control of the entire empire. “You are the boss,” said Harriman. “We are all working for you. Give me your orders.”

Telling Harriman that antitrust laws would prevent this combination, Hill remained loyal to Morgan. After he left Harriman’s office, Harriman tried to buy every remaining NP share on the market. Morgan wired orders from Europe for his company to join the fray. There was a brief panic when some speculators, expecting the price to drop, sold shares they didn’t own and frantically bid up the price to $1,000 a share to cover their contracts. (After the dust settled, Morgan, Hill, and Harriman let these speculators off the hook.)

In the end, Harriman had a majority of voting stock, but a slight minority of common stock. Though preferred shareholders could vote at the company’s annual meeting, before the meeting Morgan and Hill exercised a provision in the company by-laws to buy out all preferred stock. Harriman ended up with seats on the board but not the firm control he needed to get access to the Burlington lines.

Hill responded by creating the Northern Securities Trust, which combined ownership of the GN and NP into a company too large, Hill hoped, for anyone to try to take over. Although the companies still operated separately, the trust was “busted” by Theodore Roosevelt, a case that went to the Supreme Court and which, if it had been decided based on precedents set a few years later, Hill would have won. It didn’t matter; Hill could make sure no one would ever again make a run on his railroads.

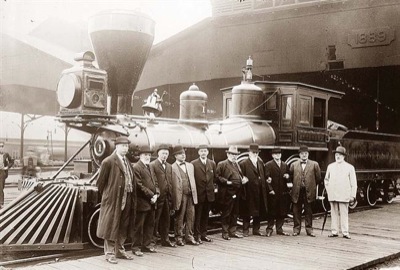

For Hill’s 70th birthday in 1908, Great Northern employees restored the William Crooks, the first locomotive owned by the St. Paul & Pacific. Hill is fifth from the right. The locomotive is now preserved at the Lake Superior Transportation Museum in Duluth.

For Hill’s 70th birthday in 1908, Great Northern employees restored the William Crooks, the first locomotive owned by the St. Paul & Pacific. Hill is fifth from the right. The locomotive is now preserved at the Lake Superior Transportation Museum in Duluth.

Harriman was defeated, but the two titans continued to fight it out in the Pacific Northwest. Harriman denied Hill access to Portland over the Oregon Railway & Navigation route up the Columbia River, so Hill built the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway on the north bank of the river. Then Hill set his sights on California, leading to, among other battles, the Deschutes River Railroad War. Through the CB&Q, he also bought rail lines extending to Dallas and Galveston, Texas.

Hill had a strong sense of honor. In 1897, on his son’s advice, he purchased extensive mineral rights in northern Minnesota that turned out to have valuable iron ore deposits. The Great Northern would earn millions of dollars hauling iron ore from these lands for at least 60 years. But Hill did not believe he should have the right to such inside dealing, so he sold all the rights to Great Northern stockholders at his cost–which turned out to be a gift worth hundreds of millions of dollars. (Of course, he was one of the stockholders, but he never personally owned more than 20 percent of the GN.)

Hill also resisted efforts by some on his board to manipulate the company’s stock for personal profit. At one point, a director proposed to create a shell company with which they could “make a melon and sell out,” Hill later recalled. “This was the time I locked the door on the Board of Directors and served notice on them that they might vote for the plan, but that would be as near as they would ever come to carrying it out.”

People called Hill a robber baron, but there was a huge difference between builders like Hill and stock manipulators like Jim Fisk. Whereas Fisk just tried to make money regardless of the consequences to others, Hill realized that his income depended on the prosperity of his neighbors and customers.

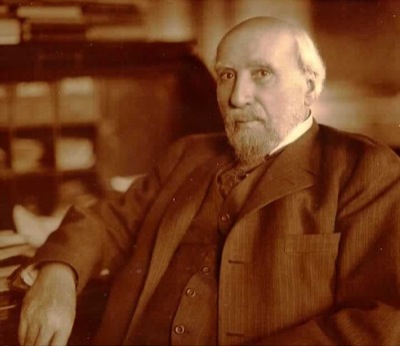

Hill in his New York office in 1915.

Hill in his New York office in 1915.

People also called Hill a monopolist, but he was fiercely competitive in all his dealings. When the Chicago, Minneapolis and St. Paul Railroad started building to the Pacific in 1908, Hill made no effort to stand in its way. “The addition of the business of new lines to the Puget Sound would greatly help that seaport and would enlarge the whole business, and in the end would do us much more good than harm,” he wrote to George Stephen.

Hill realized that railroads thrived on volume, not high rates. “What we want over our low grades is a heavy tonnage; and the heavier it is, the lower we can make the rates,” he wrote to a shipper.

Though he admitted that the Great Northern was an effective monopoly for 75 percent of the traffic it carried, Hill believed that railroads truly competed with one another by helping their regions thrive. As he wrote Stephen, “we consider ourselves and the people along our line as co-partners in the prosperity of the country we both occupy; and the prosperity of one should mean the prosperity of both, and their adversity will quickly be followed by ours.”

Next: The Conservationist

The year when Hill died “capitalism” was at it’s peak in the US and has declined ever since.

Pingback: James J. Hill, Entrepreneur » The Antiplanner

Pingback: James J. Hill, Conservationist » The Antiplanner