For parts I and II, see James J. Hill, Entrepreneur and James J. Hill, Empire Builder.

James J. Hill was acutely aware that most of the products shipped on the Great Northern Railway were agricultural, and he worried that traditional farm practices were degrading the soil. “I know that in the first instance my great interest in the agricultural growth of the Northwest was purely selfish,” he said in a speech. “If the farmer was not prosperous, we were poor, and I know what it is to be poor.”

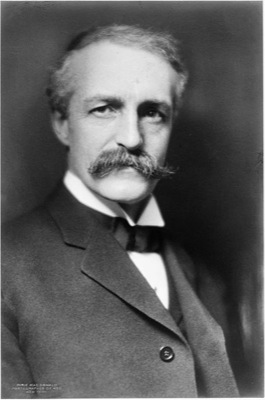

Hill lecturing farmers about soil conservation at the Stearns County (MN) Fair in 1914.

In order to promote what we would now call sustainable farming, Hill encouraged crop rotation and raising of livestock whose manure could fertilize the soil. Between 1884 and 1910, he purchased thousands of prize bulls, hogs, and rams in Europe and gave them to farmers on the condition that they make them available to their neighbors for breeding purposes.

His soil theories were not always correct, but he hired expert agronomists to start a Great Northern Extension Service to train farmers with the latest techniques. Among other things, for demonstration purposes, his extension agents actually paid farmers to follow their recommended practices to show how much greater yields they could attain.

Hill’s ardent efforts in soil conservation caught the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who (according to the New York Times) was inspired by Hill’s speeches to hold a White House conference on conservation in 1908 that was attended by almost every state governor. In fact, the real conference organizer was Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the Forest Service and a member of Roosevelt’s “kitchen cabinet.”

Although Roosevelt broke up Hill’s Northern Securities Trust, Hill gladly accepted the opportunity to speak about soil conservation at the 1908 Governors’ Conference on Conservation. Both, however, look uncomfortable to be sitting next to each other at the White House.

After Roosevelt left office, Pinchot broke with the Taft administration over who should control the nation’s conservation policy. Taft’s secretary of the interior believed with many westerners that conservation could be practiced at the state and local level. Pinchot believed that federal government should control conservation policy because only it was insulated enough from big business to be a true conservationist.

In January, 1910, Pinchot maneuvered Taft into firing him for insubordination. This polarized the conservation issue and allowed Pinchot to build an army of supporters. In September, he gathered his army, 10,000 strong, at a National Conservation Congress in St. Paul. Hill’s son, Louis, was on a committee that made local arrangements for the conference, and it was only natural that Pinchot asked Hill to speak about soil conservation.

Gifford Pinchot shortly before being fired by Taft.

Hill, however, did not support Pinchot’s notions of federal control. Rather than talk about soil conservation, he used his time to lambast federal bureaucracies and waste.

“The need of the hour is to conserve conservation,” thundered Hill. “It has been used to forward that serious error of policy, the extension of the powers and activities of the national government at the expense of those of the states.” The problem with national control, he said, is that “the machine is too big and too distant; its operation is slow, cumbrous and costly.”

Hill proceeded to dissect federal conservation programs–reclamation, forestry, minerals, soils–and show how they wasted money and failed to conserve. Regarding forests, he noted in a clear swipe at Pinchot, “It might be said of certain administrators that ‘they make a desert and call it conservation.'”

“Conservation is wholly an economic, not in any sense a political principle,” he argued. Hill added that “conserving capital and credit” was just as important as conserving resources, yet federal budgets since 1890 were growing far faster than the nation’s population and wealth.

Other than President Taft (whose noncommittal speech was boycotted by Pinchot), Hill was the only major conference speaker representing the local view. “Hill speaks for myriads of conservative Americans who foresee the waste of millions of dollars in Federal conservation along with results far from the best possible,” declared a New York business journal.

Hill’s speech created an uproar. In retaliation, one of Pinchot’s allies, Francis Heney, gave a speech the following day accusing Hill of being “responsible for the great waste in the natural resources of our country.” “Do you know what we gave Mr. Hill to build that railway?” Heney asked. “We gave to Mr. Hill 60,000,000 acres of land — a strip 2,000 miles long, 40 miles in width through the territories and 20 miles in width through the states.”

“The Great Northern never received a dollar in money nor an acre of land from the federal government,” Hill responded the next day. “If Mr. Heney’s charge relates to the Northern Pacific instead of the Great Northern, the federal grant to the Northern Pacific was made fifteen years before I went into the railroad business and at a time when I was working for $75 a month.”

Hill died in 1916, and Pinchot in 1946. If either had come back in, say, 1952, it would have appeared that Pinchot’s view was vindicated. Newsweek magazine called the Forest Service “one of Uncle Sam’s soundest and most businesslike investments.” The agency, reported Newsweek, actually earned a profit. What is more, it managed the national forests in a way that pleased almost all forest users.

The agency’s popularity, and its profitability, was short lived. Records indicate that it only made a profit three more years, and never after 1969. Moreover, within two decades the Forest Service was embroiled in controversy, mainly over its decision to manage most of its forests by clearcutting them. Clearcuts, the agency argued, were scientifically the best way of managing the forests. But they were ugly and turned many of its former supporters against it.

Moreover, a close scrutiny of its budget revealed that the main beneficiary of clearcuts was the Forest Service itself. Taxpayers actually lost money on most of the timber the Forest Service sold. The Forest Service itself admits that its poor management of the national forests over the past century has led to huge fire and other forest health problems.

As a result, some would say Hill’s view has been vindicated today. Professor Robert Nelson of the University of Maryland argues that the Forest Service’s mismanagement indicates that the national forests should be turned over to the states. Professor Sally Fairfax of the University of California at Berkeley doesn’t think the lands should be given to the states, but she has examined the state school lands and found the fiduciary trust model to be a compelling alternative to the Forest Service model of relying on official altruism.

Depending on how you look at it, Hill might be described as either behind his time or ahead of it. His 1910 speech would have been perfectly understood by American’s living in Henry David Thoreau’s era or by many Americans today. While management of the nation’s resources remains controversial, policy makers today could do worse than to look to James J. Hill for ideas on how to resolve those controversies.

Next: James J. Hill’s Legacy

Like I’ve said in the past: The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment.

Though people like JJH or HDT are from a much different era.

I always thought this was a big contradiction on your part ROT.

Conservation was one part of Hill’s past I was unaware of, knowing only the outline of the history of the Great Northern. I was sure you were going to resurrect one of Hill’s most famous quotes, but you didn’t. So I will: “The passenger train is like the male teat: neither useful nor ornamental.”

Wow that’s bigoted!

Aarne Frobom,

I’ve searched all of Hill’s speeches, articles, and biographies. I haven’t been able to find any evidence that Hill said that. He did once say that the purpose of the railroad was to move freight and he didn’t build it to provide tourists with the best scenery.

That’s not it, the purpose of the railroad to him was to make money!