For parts I, II, and III, see James J. Hill, Entrepreneur, James J. Hill, Empire Builder, and James J. Hill, Conservationist.

In 1912, at the age of 74, James J. Hill retired as chairman of the board of the Great Northern Railway. “Most men who have really lived have had, in some shape, their great adventure,” he wrote in a letter to his friends and employees. “This railway is mine.”

James and son Louis Hill at a Minnesota State Fair. Hill often offered prizes for the best livestock and produce shown at state fairs.

Hill and his wife Mary had nine children including three sons. James was nominally a Presbyterian but Mary was Catholic, and when their eldest son, James N., married a divorced woman, she banished him from the household. That left the second son, Louis, as the heir apparent. (James N. moved to Texas and earned millions investing in the Texas Oil Company.)

In 1910, Congress passed a law requiring all railroads to submit any rate changes to the Interstate Commerce Commission for approval. This greatly hampered the railroads’ ability to respond to day-to-day changes in demand and provide new services. Decades later, railroad managers would be accused of being stodgy and failing to innovate or compete against truckers, when in fact the strict government control prevented them from doing so. (Since deregulation in 1980, railroads have significantly gained market share.)

Hill foresaw the problems with the 1910 law. “By the time you’re forty,” he told Louis (who was 38 in 1910), “be out of the railroad business.” As a new business, Hill bought several banks and merged them into the First National Bank of St. Paul, the second largest bank west of the Mississippi. (Today, after many mergers and acquisitions, this bank is now part of U.S. Bancorp.)

Hill’s hope was to reform the agricultural credit system that was the bane of the American farmer. “I still have about five-and-a-half years of work ahead of me,” he told a reporter in 1913. Unfortunately, he didn’t finish it, dying in 1916.

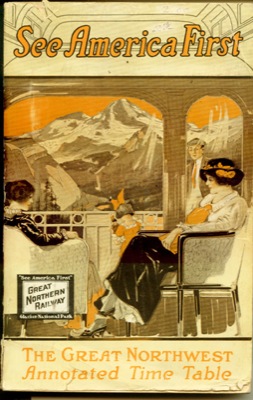

To encourage tourists to visit Glacier National Park, the Great Northern Railway coined the slogan “See America First” in 1912.

Louis didn’t follow his father’s advice, chairing the board of the GN until 1929 and remaining on the board for the rest of his life. But he seemed more interested in first persuading Congress to create Glacier National Park (which happened in 1910) and then in building a fabulous chain of hotels in and around the park. Although he became the railroad’s president when James retired in 1910, for a time, he left the management of the railroad to others so he could work on the Glacier Park project.

Before his death, James confided to Louis that a young man named Ralph Budd would make the best president for the Great Northern when Louis was ready to retire from that position. Louis followed this advice in 1919, making Budd, at 40, the youngest railroad president in America. In 1929, Budd oversaw completion of a 7.9-mile tunnel through Washington’s Cascade Mountains, which greatly eased the GN’s winter operations.

To commemorate the tunnel and his mentor, Budd renamed the railroad’s premiere train the Empire Builder. Today, Amtrak’s Empire Builder still mostly follows the Great Northern route and is both Amtrak’s most popular long-distance train and the oldest American train name still in continuous use.

Also under Budd’s supervision — and partly prompted by Arthur Curtis James, a financier who had holdings in the Great Northern, Western Pacific, and several other roads — the Great Northern finally achieved Hill’s dream of building into California with a line from Bend, Oregon, to Bieber, California, where it met the Western Pacific’s line to Oakland. Together with the Santa Fe Railroad, the GN and WP could offer service from Seattle to Los Angeles in competition with the Southern Pacific (now Union Pacific).

Raph Budd remained president through 1931, taking the reigns at the CB&Q in 1932 where he oversaw development of the streamlined passenger train, the first Diesels in mainline service, and the first dome cars. In 1951, Ralph Budd’s son John became president of the Great Northern, meaning either a Hill or a Budd was at the helm for all but a few years of the railroad’s existence.

BNSF’s James J. Hill Network Operations Center near Ft. Worth. Photo by Dick Tinder.

That existence, at least under the GN name, ended in 1970, when John Budd oversaw the merger of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railways, bringing with them the CB&Q and Spokane, Portland & Seattle (the road Hill built in 1908 to compete with Harriman’s route down the Columbia River). Initially calling itself the “Great Northern Pacific & Burlington,” quickly shortened to Burlington Northern, the railroad later merged with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe and now is known as the BNSF.

BNSF is headquartered near Ft. Worth, TX, where every single train on the 32,000-mile system is dispatched out of the James J. Hill Operations Center. The headquarters also displays one of Hill’s office desks and other Hill memorabilia. BNSF adopted a color scheme for its locomotives that is supposed to carry reminders of all the predecessor roads, but in fact is most reminiscent of the orange-and-green colors that the Great Northern adopted in 1939. In short, the BNSF really is the fulfillment of Hill’s vision.

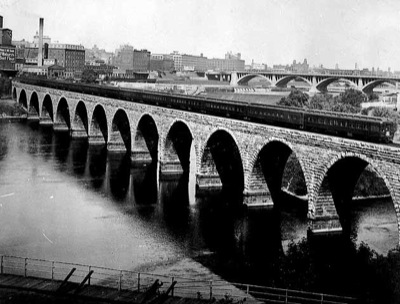

Hill once said building the Stone Arch Bridge was the most difficult project he ever undertook. For nearly a century, trains of most Minnesota railroads shared the bridge to cross the Mississippi between St. Paul and Minneapolis.

Hill built for the ages. While most early railroad structures were made of wood, as soon as he took over the St. Paul & Pacific he began building shops and other buildings out of brick and stone that have lasted to this day. Several buildings of the Jackson Street Shops have been converted to offices. The Stone Arch Bridge across the Mississippi River is still used as a bike/pedestrian path. The 1887 Great Northern Railway Building has been converted to lofts. The 1916 railway-and-bank building, which was divided into thirds to house the First National Bank, Great Northern, and Northern Pacific railways, is still used as a bank and office building. (The building had a door connecting the offices of the presidents of the nominally competitive Great Northern and Northern Pacific railways that supposedly was never unlocked until the railroads merged in 1970.)

James J. Hill’s home. The house on the left belonged to Louis Hill.

Hill also built his family a 36,000-square foot home in St. Paul, practically across the street from the St. Paul Cathedral that — rumor had it — was built with donations Hill made in honor of his wife. (Certainly his wife made major donations, but historians have not been able to verify whether Hill funded the bulk of the cathedral’s construction cost.) There is no doubt that Hill did contribute hundreds of thousands of dollars to a wide variety of churches and schools, mostly in the Minnesota-to-Washington region that he regarded as his home. When Hill’s wife, Mary, passed away, her children gave the family house to the church, which has since sold it to the Minnesota Historical Society.

Louis and his wife left their fortune — which was, of course, a good part of James’ fortune — to the Louis and Maude Hill Family Foundation, now known as the Northwest Area Foundation. This foundation gives nearly $25 million a year to a wide range of charities and non-profit groups located in the eight states once served by the Great Northern Railway.

The James J. Hill Reference Library is on the left; the right half of the building is the St. Paul Public Library.

Inspired by by a New York library built as a memorial to J.P. Morgan, in 1911 Hill commissioned the construction of the James J. Hill Reference Library in downtown St. Paul. Morgan’s has since become a museum and the Hill library, which shares a wall and architectural style with the St. Paul Public Library, carved a niche for itself as a business reference library.

Office buildings, bridges, and other structures are really only reminders of Hill’s true legacy, which was the development of new business models that allowed the opening of the Northwest. The New York Times estimated that Hill’s railroad opened 65 million acres of land to farming by 400,000 families. “He has captured more territory with the coupling pin, and made it habitable for man,” said Washington Senator John Wilson, “than did Julius Caeser with the sword.”

This was only possible because Hill had a transportation vision that few others, particularly in the West, understood. Most fortunes are based in part on luck, but Hill’s luck was that he was Minnesota’s foremost transportation expert at a time when none but he and his partners could see any future in the bankrupt St. Paul & Pacific Railroad — and that he was young enough to have the energy to fulfill that future. Hill turned that luck, expertise, and energy into an empire that has recognizably lasted to this day.

“When we are all dead and gone,” Hill once told his employees, “the sun will still shine, the rain will fall, and this railroad will run as usual.” It still does.