The United States has the most efficient and productive railroads in the world. Not coincidentally, the United States also has the most private railroads in the world. Other than Canada, almost every other country that has railroads has nationalized them.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Private railroads operate with very different goals from those that are owned by the government. Private railroads seek to maximize profits, and to do so they must be as efficient and productive as possible. Government-owned railroads seek to maximize political popularity, and to do so they must favor actions that are highly visible and often are highly inefficient and unproductive because economic costs translate into political benefits. Continue reading

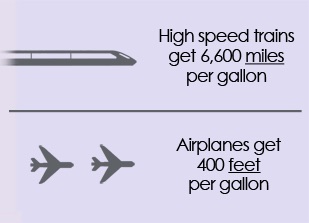

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.