After last week’s shooting, restoring light-rail service to Silicon Valley will take “weeks or months, not days,” says a representative of the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA). In place of light rail, the agency was providing “bus bridges” to serve light-rail routes.

On Monday, however, VTA announced that it would discontinue such bus bridges. Instead, it “is directing all resources to the regular bus network that serves the majority of our riders who rely on public transit the most.” In other words, light rail serves mainly high-income workers who aren’t riding anyway because they are working at home. So those who were still riding light rail before last Wednesday must hustle to find alternate transportation such as riding buses that don’t necessarily parallel the light-rail lines.

If these light-rail lines were so important to the region that they had to be built, it seems like they would be important enough to keep running buses serving their customers while the rail system is out of commission. VTA is tacitly admitting that it was a mistake to build them in the first place. Continue reading

Wheels that are too narrow will slip off tracks at joints like these, known as “frogs.”

Wheels that are too narrow will slip off tracks at joints like these, known as “frogs.”

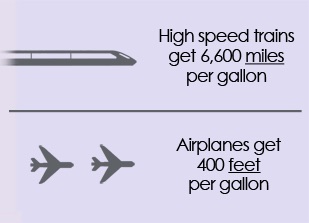

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.

US HSR’s claim that high-speed trains can go 6,600 miles on one gallon of fuel is absurd, and its claim that airliners can only go 400 feet on one gallon is also wrong.