In 1975, I set out to replace Gordon Robinson’s “if it’s pretty, it’s good; if it’s ugly, it’s bad” mantra with a more scientific approach to environmental issues such as wilderness, timber cutting, and public land management in general. I was fortunate to work with James Monteith, whose background in biology gave him a similar approach, as well as other experts and specialists.

By 1990, it was clear that we had changed the environmental movement from one based on emotion to one based on science and technology. It was also becoming clear just how successful we were, as national forest timber sales were declining and people inside the Forest Service, from top to bottom, were trying to reform the agency from the inside. We had no idea that, by 2001, timber sales would fall by 85 percent, but we could still feel good about our work.

Unfortunately, two events would undo the revolution that had taken place within the environmental movement: the fall of the Soviet Union and the election of Bill Clinton to the White House. When the Soviet Union fell, it appeared to be a victory of free markets over government planning. “Socialism” was considered a tainted idea, just like communism and fascism. Polls showed that the vast majority of Americans agreed with the statement that “government messes everything up.” Continue reading →

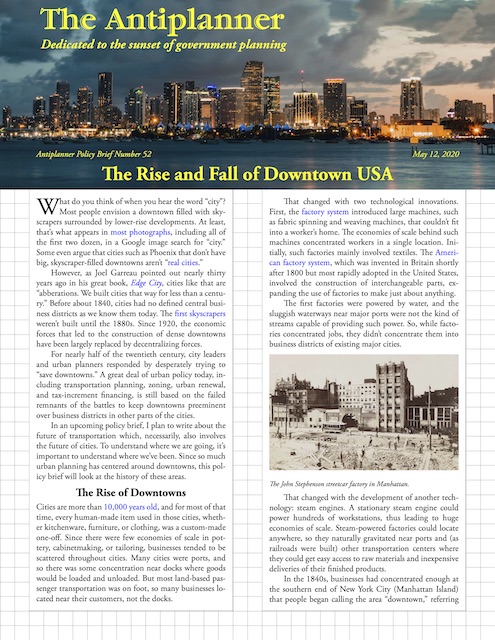

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.