In September, 2021, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill abolishing single-family zoning. This bill was a victory for the Yes in Other People’s Back Yards (YIOPBY) movement, as well as for urban planners who sought to densify California urban areas, which are already the densest in the nation.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a five-page PDF of this policy brief.

It was also a victory for the Cato Institute, which was proud of the fact that it was working hand-in-hand with left-wing groups that sought to force Californians to live in ways in which they didn’t want to live. Cato’s work was led by Michael Tanner, whose previous experience with housing issues was nearly nil. In supporting this movement, Cato and Tanner ignored everything I had written in two books and seven policy papers for Cato over the previous fourteen years.

Cato hired me in 2007 explicitly to work on urban land-use and transportation issues. When it did so, it noted that my previous “work showed that urban planning was not making cities more livable, but instead was increasing congestion and making housing less affordable.”

During my first year, Cato published my 416-page book, The Best-Laid Plans, which showed that urban planners had an irrational mania for density that was making housing less affordable in regions that attempted to stop the growth of low-density suburbs. In the same year, Cato published a paper that I wrote showing that San Jose’s urban-growth boundary was rapidly densifying that city to the detriment of congestion and affordability, along with two other papers on housing issues.

In 2009, Cato published The Myth of the Compact City, a paper I wrote showing that all the arguments for densification were faulty. We didn’t need to force people to live in high densities to save farms, forests, and open space because all the urban areas of the country occupied just 3 percent of the nation’s land area. Nor would density reduce air pollution or greenhouse gas emissions: people living in dense areas actually use more energy for transportation than those in low densities because they drive in more congested conditions, while multifamily housing uses more energy per square foot than single-family homes.

The Nightmare of Densification

In 2012, Cato published American Nightmare, which showed that the vast majority of Americans—most surveys indicated around 80 percent—either happily lived in or aspired to live in single-family homes. In fact, more than 75 percent of households did live in single-family homes in Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Nebraska, Ohio, and Pennsylvania–states that weren’t trying to control urban sprawl–while states trying to limit suburban growth including California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington had rates well below 70 percent.

American Nightmare also showed that the desire for single-family housing went back at least into the nineteenth century, but transportation had been the main barrier to that dream. Early cities were dense because the main form of transportation was on foot, so people who didn’t want to walk long distances to work often lived in multifamily housing. The development of steam-powered commuter trains in the 1830s, electric streetcars in the 1880s, and affordable mass-produced automobiles in the 1910s allowed successively lower-income people to live in single-family homes.

American Nightmare further showed that the desire for single-family housing was strongly associated with the desire for homeownership. Census data show that nearly 83 percent of occupied single-family homes are occupied by their owners, while nearly 87 percent of multifamily dwellings are occupied by renters.

In 1890, a builder named Samuel Gross sold two-bedroom, one-bath homes like these for about $1,000, the equivalent of $25,000 in today’s money.

In 1890, the main barrier to homeownership was not the price of housing, which was affordable to nearly everyone who could deal with the transportation issue. For example, homebuilders in 1890 Chicago sold brand-new homes with private yards and indoor plumbing for as little as $1,000, or about $25,000 in today’s money.

Instead, the main barrier to urban homeownership was that people didn’t want to invest in a home only to see its value destroyed by the introduction of incompatible uses next door or nearby. Despite the low cost of homeownership, less than 18 percent of urban households owned their own homes in 1890, compared with well over 60 percent of rural households.

In the 1890s, developers discovered that adding deed restrictions limiting home sites to single-family homes led to faster sales. The deed restrictions didn’t increase the cost of housing but they did increase the desirability of homeownership.

In the 1900s, urban planners developed single-family zoning as a way of replicating the benefits of such deed restrictions for existing neighborhoods of single-family homes. By 1960, almost every city in America except Houston had passed a zoning ordinance that zoned part of the city for single-family housing. Since the 1950s, virtually all new single-family housing has been built either in areas zoned for single-family housing or with deed restrictions.

Opponents of single-family zoning correctly point out that there was a racial component to some early deed restrictions and zoning. The Supreme Court, however, quickly ruled that racist zoning was unconstitutional and eventually did the same for deed restrictions. If every institution that was ever tainted by Jim Crow laws were thrown out, we would no longer have public schools, urban transit, restaurants, or drinking fountains.

Americans responded to deed restrictions and zoning by massively increasing homeownership. Between 1890 and 1960, urban homeownership rates more than tripled to over 58 percent. In essence, Americans showed that they didn’t want to live in just a single-family home; they wanted to live in neighborhoods of single-family homes. There were good reasons for this: such neighborhoods tended to be quieter, with less congestion, less crime, and lower taxes.

The United States in the 1960s enjoyed the lowest levels of wealth inequality in its history, and high homeownership rates were an important part of that. Homeownership was accessible to almost anyone with a job, and people who owned their own homes were able to use the equity in their homes to start small businesses, put their children through college, or fund their retirement.

Urban planners were unhappy with the United States being a nation of suburbs. Stimulated partly by a wacky architect who called himself Le Corbusier and thought that everyone should live in high-rise housing and partly by a wacky architecture critic named Jane Jacobs who thought that mid-rise housing was the epitome of urban living, planners began advocating strongly for more compact cities in the 1970s. (Planners influenced by Jacobs call themselves New Urbanists to distinguish themselves from the “old urbanists” influenced by Le Corbusier.) Significantly, Le Corbusier himself never lived in a high rise while Jacobs lived in a row house, not a mid-rise apartment, in Greenwich Village and used the proceeds from her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, to move from there into a detached single-family home.

Planners rationalized the contradiction between American preferences for single-family homes and planners’ preference that most live in apartments by assuming that American preferences were shaped by biased government policies. In 1990, a planner named Douglas Porter urged planners to use metropolitan governments to halt urban sprawl and force people to live in higher densities, policies that became known as smart growth.

In 2008, a planning professor named Arthur Nelson became widely celebrated for predicting that, by 2025, there would be 22 million “surplus” suburban homes, and the suburbs would become slums as middle-class Americans were going to move into central city mid-rise and high-rise apartments and condominiums in droves. Nelson urged urban planners to prepare for this by rezoning both suburbs and cities to higher densities, and the movement to abolish single-family zoning is part of this crusade. The return to the cities never happened and COVID has accelerated decentralization of urban areas, yet planners continue to promote densification.

Blaming Single-Family Zoning

By the time American Nightmare was published, housing prices had reached crisis levels in many urban areas, all of which had drawn urban-growth boundaries or taken other steps to restrict rural development. Planning advocates then proposed a new argument for densification of cities: They claimed that single-family zoning had made housing expensive, and abolishing single-family zoning in states like California and Oregon would make housing affordable again.

Planners had previously proposed many other ways of making housing more affordable, most of which were ineffective if not counterproductive. One common proposal was inclusionary zoning, a requirement that developers sell or rent a fixed share, usually around 15 percent, of the dwellings they build to low-income households at below-cost prices. Economists showed that this policy makes housing less affordable by leading developers to build less housing and selling or renting the market-based housing they did build for higher prices to make up for the losses from the below-cost housing.

The argument that single-family was responsible for high housing costs was just as absurd as inclusionary zoning. My 2008 Cato paper, The Planning Tax, showed that housing in 1970 had been affordable everywhere in the country except Hawaii despite every major city except Houston having single-family zoning. Housing affordability in Houston, which had no zoning, was about the same as in Dallas, which had single-family zoning.

Housing was expensive in Hawaii only because that state was the first to introduce growth-management planning policies in a 1961 land-use law that restricted development of rural areas. As California, Oregon, Washington, Florida, and states in the Boston-to-Washington corridor and cities along the Colorado Front Range adopted similar policies, their housing affordability declined as well.

A 1975 Environmental Law article labeled such restrictions on rural landowners the New Feudalism because, while they allow people to own land, they effectively transferred the development rights to that land to the government. Collectively, these land-use laws represent the greatest taking of private property since the communist Chinese collectivization of farms in 1953.

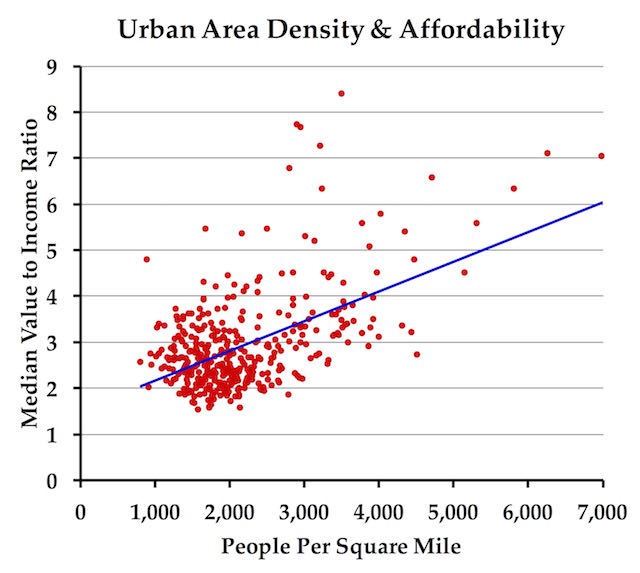

2010 census data for more than 380 urban areas show a clear negative correlation beween density and housing affordability.

In California, cities and counties had drawn urban-growth boundaries in the 1970s that, as of 2010, forced 95 percent of the population of the state to live on just 5 percent of its land area. Only 31 percent of the six counties in the San Francisco Bay Area had been developed, while development of the remaining 69 percent is prevented by growth boundaries. Only 32 percent of Los Angeles, Orange, and Ventura counties had been developed. Thanks to growth management, California urban densities were twice as great as the average density of urban areas in the other 49 states.

Some California cities had initially intended to expand growth boundaries as their populations grew, but the 1990 California Environmental Quality Act led to a requirement that any such expansion be preceded by a detailed environmental impact report, which typically cost about $20 million. No one was willing to spend this money so no boundaries were expanded, and by 2000 California had the least affordable housing in the nation.

Nor would abolishing single-family zoning make housing affordable again. All available data showed that densification inevitably made housing less affordable. A comparison of urban area densities with housing affordability (measured by dividing median home prices by median family incomes) using 2010 census data shows a clear negative correlation between the two. The Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland, and San Jose had all significantly increased in density since 1970, and those increases were accompanied by huge declines in affordability.

There are several reasons why densification, at least when enforced by growth management, is incompatible with housing affordability. First, land prices in regions that restricted rural development are much higher than regions that did not try to manage growth. A 2017 review of urban land prices, using 2005-2010 data, found that the average price of land in regions such as San Francisco and Los Angeles were more than ten times greater than in regions such as Atlanta and Dallas.

High land prices mean that housing in a growth-managed area must be much denser than in an unrestricted area to be the same price. This requires multifamily housing usually three or more stories high. As a California developer named Nicholas Arenson testified to a San Francisco Bay Area planning commission, such multifamily housing costs much more to build, per square foot, than single-family housing, and “sells at a discount to all” single-family dwellings. Arenson estimated that construction costs per square foot were 50 percent more for three stories, 100 percent more for four stories, and 200 to 650 percent more for taller buildings. These higher costs are due to the need for elevators and increased use of steel and concrete in the structures.

Another reason why abolishing single-family zoning won’t make housing more affordable is labor costs. When housing costs are higher, construction workers need to earn more to be able to live in the area in which they work. According to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the mean construction industry wage in California is nearly $31 an hour while in Texas it is just $22 an hour. As long as housing is expensive, it will cost more to build housing in expensive markets.

In 1947, Henry J. Kaiser sold these California homes for up to $10,500, or about $135,000 in today’s money. Today, thanks to urban-growth boundaries, they sell for well over $1 million.

Finally, history shows that the housing industry produces affordable housing only when it can build hundreds of homes at a time on vacant land, as Henry J. Kaiser did in Oregon and California in 1946 and 1947, the Levitt brothers did in the New York-New Jersey-Philadelphia areas in 1947 through the early 1950s, and numerous homebuilders have done in various master-planned communities since then. Building a few one-off apartment complexes in already developed areas is not going to be efficient.

Confronting Cato

In 2017, I wrote a paper pointing out these facts and submitted it to Cato. I was stunned when it was rejected and they called me a “central planner” because I supported single-family zoning. When I said that abolishing single-family zoning wouldn’t make housing affordable, they told me it was necessary to restore people’s property rights. When I said that the people who lived in single-family areas wanted such zoning and that they actually considered it a property right, they told me such people were racists. These are the kinds of woke answers I would have expected from left-wing groups, but not from Cato.

Homeowners who argue that single-family zoning is a property right are historically accurate. Such zoning was created to make homeownership more attractive, and it succeeded. If such zoning hadn’t been created, then virtually all the single-family neighborhoods built in the twentieth century would have had deed restrictions to accomplish the same thing. Since single-family zoning has been around for 60 to 100 years, almost no one who owns a home in one of these neighborhoods today “lost” any property rights when the area was zoned; instead, most were happy to buy in areas so zoned or protected with deed restrictions. Zoning land as a substitute for deed restrictions and then yanking away that zoning betrays the homeowners in such neighborhoods.

I was aware when I wrote the 2017 paper that a group of people calling themselves market urbanists claimed to believe in free markets yet sang the praises of density even though most Americans did want to live in dense neighborhoods or cities. Like the new urbanists, these market urbanists were heavily influenced by Jane Jacobs, yet neither she nor they understood that the dense neighborhoods she praised were vestiges of the nineteenth-century period when people had to live in density so they could be within walking distance to work, and that most of the people who lived there got out as soon as they could.

The market urbanists who support densification don’t understand how housing markets work. They don’t realize, for example, that in the minds of most Americans an apartment is not an equivalent substitute for a single-family home. They think that building a thousand 1,000-square-foot apartments will do as much to meet housing needs as building a thousand 2,200-square-foot single-family homes, when in fact the demand for the latter remains much higher than for the former.

The self-described market urbanists also fail to recognize the role the suburbs play in keeping housing affordable in the cities. Land is more expensive in the central cities than in the suburbs, but so long as the suburbs are allowed to grow, they will stay affordable and the central cities will remain affordable as well, though still more expensive than the suburbs. If growth-management policies prevent the suburbs from meeting housing demand, then prices will rise dramatically in both the cities and suburbs. By focusing on the cities instead of the suburbs, they arrive at wrong-headed policies such as eliminating single-family zoning.

Market urbanists have a blind spot when it comes to urban-growth boundaries and other growth-management policies. I once debated Emily Hamilton, a market urbanist with the Mercatus Center. She asserted that San Francisco was surrounded by the Pacific Ocean and had nowhere to grow but up. She apparently didn’t realize that to the north, east, and south of San Francisco was plenty of vacant land, all within the San Francisco metropolitan area, that was outside of urban-growth boundaries but otherwise suitable for development.

I was also aware that some Cato scholars were market urbanists. One Cato scholar told me that housing in Washington DC was expensive because of the federal law that prevented buildings from being taller than the U.S. Capitol. The scholar completely ignored the agricultural preservation rules that kept two-thirds of Montgomery County, Maryland and 80 percent of Loudoun County, Virginia from being developed. The scholar had no answer when I pointed out that tens of thousands of residential buildings in Washington didn’t come close to the height limit, so that limit couldn’t be the cause of high prices.

What I didn’t know when I wrote my 2017 paper was that Cato was or soon would be negotiating to obtain funding from two foundations to work with progressive groups in California in support of abolishing single-family zoning. This became known as the California Poverty and Inequality Project and it was led by Michael Tanner. The project held numerous conferences and published several papers and articles. Despite my two Cato books and numerous Cato papers on housing issues, I was never once consulted on this project.

I offered to debate the issue with other Cato scholars and was turned down. In fact, I was firmly told that Cato would not publish anything I wrote on this topic. My 2017 paper was eventually published by the Grassroot Institute. This may have upset some people at Cato, but I had always assumed that working for Cato gave them first right of refusal for anything I wrote but did not give them the right to forbid me to submit articles they had rejected to other publishers.

Tanner’s California project ended up making five recommendations for making housing more affordable, including ending single-family zoning and eliminating restrictions on tiny homes. None of the recommendations said anything about the urban-growth boundaries that were truly making California housing expensive, and there is no evidence in anything Tanner has written to indicate that he was even aware of these boundaries, which he would have been if he had read any of my Cato books or papers on housing.

California’s law abolishing single-family zoning requires cities to allow eightplexes in areas currently zoned for single-family housing. When that fails to make housing more affordable, some cities will no doubt allow even higher densities. When those densities fail, the cities will demand increased taxes to subsidize “affordable” housing for a few lucky low-income households. But building affordable housing—that is, subsidized housing for low-income families—does not make the overall housing market more affordable.

“Smart growth is the new Jim Crow,” says California journalist Joseph Perkins.

“Smart growth is the new Jim Crow,” says California journalist Joseph Perkins.

In the 1960s, when wealth inequality was at its lowest, American urban areas had single-family housing for almost everyone except young families just starting out, recent immigrants, and economically oppressed blacks. If housing remained affordable as Jim Crow laws were repealed, the United States would have reduced its income inequality still further. Instead, many states and cities enacted these planning restrictions, prompting California writer Joseph Perkins to say that “smart growth is the new Jim Crow.”

Tanner envisions cities that have single-family homes for middle- and upper-middle class families and apartments and tiny homes for working-class families. That is not a way to reduce poverty or inequality.

Cato thought it was promoting a free market. But you can’t have a free market in housing when 95 percent of the land is off limits due to government regulation. Cato thought it was helping to make housing affordable. But it was actually making the single-family housing that most Californians want even less affordable.

When Cato fired me in December 2021, the reason given was that my position had been “eliminated.” But I received only one poor performance review in all the years I worked at Cato, and it was solely because I disagreed with other Cato staff about single-family zoning. Whether they fired me for this issue or not, what hurt the most is that Cato valued the opinions of pro-planning, pro-density groups more than the analyses conducted by its own housing expert presented in Cato’s own publications.

In doing so, Cato sold out the homeowners who expected their single-family neighborhoods to remain quiet and stable. It sold out the owners of the rural land who lost the rights to develop their land when the growth boundaries were drawn in the 1970s. It sold out potential homebuyers who would prefer to own single-family homes but will be unable to do so because few new such homes will be built and some existing single-family homes will be torn down to build apartments. Finally, it sold out taxpayers who will be forced to pay higher taxes to make high-cost apartments “affordable” to moderate-income families. Regardless of what it did to me, Cato should be ashamed of these destructive compromises with anti-free-market groups.

Expensive” is a very subjective term. A lot of people CAN actually afford DC or LA or NYC, but they don’t want to live with roommates or in a studio apartment. They want a one bedroom penthouse downtown or they want to buy a property so they can be like the baby boomer generation with kids and a dog; only urban.

When this is not possible with their income, they claim it is “too expensive”. If something you want is too expensive for you in a given area, that means you should do one of two things; Move or focus your energy on making more money.

Getting rid of the Urban growth boundaries in Oregon or Califirnia wouldn’t deflate the prices, it’d collapse the artificially inflated real estate prices that major real estate corporations and lobbyists have fought TOOTH and Nail to keep that way, THEIR Equity and wealth is tied into this. You think the government who depends on the tax money from this is gonna say “Meh, we’ll shutdown UGB’s”

California and Oregon are expensive, it’s urban growth boundaries are not solely government based they’re demand based; like everyone wanting to be near the coast and foremost of all Geography based………… Mountains and agriculture to the north and East, Pacific ocean to the west, Scorching desert to the East and that shithole called Mexico to the South.

You wanna live in the desert; so does Oregon have arid regions past the Cascades. You wanna live there, that’s fine, but this delusion you can take with you the East Coast vegetation and style of housing. Get used to water restrictions, driving 200 miles to go somewhere interesting, spending a lot of your time indoors with the AC on cause it’s Hot.

Lennar corporation has shitloads of money, they should build artificial islands off the California coast like Florida did in the 1920’s. Beverly hills has a population density of 33,000 per sq mile, so a 10 sq mi island can host over 300,000 or basically every rich A-hole in Los Angeles. 90210………… 2.0

And free up real estate for average folks to afford again.

There are three things wrong with the Antiplanner’s comments.

1. Banning single family zoning does not ban the building of single family houses. It lets the “free market” decide that should be built on a piece of land not less restrictive zoning which free market people should be in favor of.

2. He creates a False equivalence fallacy stating that someone is either for densification OR for expanding or removing urban growth boundaries but cannot be for both. And if you don’t state you are against urban growth boundaries then you are for them.

3. He states that there is all this developable land in California that the state and counties wont let be development but doesn’t state how much of that is park space, forest, nature reserves, deserts, etc. you know greens pace for residents and visitors to enjoy or that is geographical undevelopable. According to his logic NYC is 14% park space meaning there is 14% of the city that the government bans development.

“Banning single family zoning does not ban the building of single family houses. It lets the free market decide ”

This is what’s unclear to me. It would seem that if you’re letting the free-market decide, then you’d be banning all types of zoning on housing — not just the single family type.

My hunch is that zoning will still be completely determined by politicians, but that the single family type is not an option.

Does anybody have details to point to?

Sketter—” It lets the “free market” decide ”

BULL SKAT – there is NO FREE MARKET in those areas. Get rid of government restrictions on building first. Then a few decades later get rid of the zoning and you will see little effect.

BTW, why not do it the old fashioned way – let the residents decide on their own neighborhood zoning instead of forcing it on people? Simple answer is that they would NOT allow the destruction of their own neighborhood.

”

When I said that abolishing single-family zoning wouldn’t make housing affordable, they told me it was necessary to restore people’s property rights.

” ~anti-planner

This is is especially baffling. The government declaring that R-1 zoning will also allow for duplexes and quads does nearly nothing to recognize nor restore people’s right to property. The government still enforce setbacks, still limits how much of the lot you can use for the house, still limits the use of the property to residential, still dictates how many screws will hold in your drywall, still declares that you have to install a radon detector ( pure poppycock, btw ), still force you to hook up to their local utility monopolies for water and power and pay for those threw the nose even if you don’t use them, still ban you for putting a well in to get water, still dictate that you can’t have a garden in your front yard, still ban you from parking on your front lawn, etc, etc, etc.

It’s the smallest of tweaks when it comes to property rights. It’s nothing to celebrate.

”

1. Banning single family zoning does not ban the building of single family houses. It lets the “free market” decide that should be built on a piece of land not less restrictive zoning which free market people should be in favor of.

” ~ Sketter

Congratulations for creating a straw man. Your mother will be proud even if normal folks recognize it as a brain dead move.

@prk166,

Your not refuting or even giving a counter argument to anything that I posted. How does reducing government’s control on land not promote a free-market stand point?

Reading this mostly makes me sad for the Antiplanner. I hope the future will show the Cato Institutes how wrong they are.

Sketter,

As I wrote in the post, it’s not a free market when regulators take 95 percent of the land out of the market.

@Antiplanner

As you seem to do with your argument against banning single family zoning. You don’t want to admit that banning single family zoning supports free market principles but you will only talk about UGB when it comes to that. It sounds like the AP is all for less regulation when it comes to housing EXCEPT when it comes to less regulation for single family housing.

People on this thread are pointing out the contractions that got the Antiplanner fired from CATO. Everyone including CATO can see them, except himself.

Wrong. But maybe you would like to point out the contradictions, keeping in mind that land is NOT A FREE MARKET due to UGBs and many other restrictions.

I should make it clear that I agree 100% with the Antiplanner and believe that he makes his case very well.

It’s obvious that both academia and think tanks are pretty pay-to-play. My only real question from this is how much money did they receive to start pushing this agenda? Also, who paid such amounts.

@Sketter, you still have not corrected your false claim. If you were serious about a constructive conversation you would do so.

@janehavisham, you don’t know what lead to them parting ways. Thank you for making clear that you’re you’re willing to pontificate about things you don’t have evidence for.

As for the claim that the changes in Minneapolis and California to R-1 zoning are not banning signal family housing, are you all that brain dead?

Y’ll just lived through “one and done” to now where not only ain’t it one and done, it’s constant for life but on top of that, if you won’t – or as in most cases – can not get the covid shot, you’re banned from all sorts of things.

Tweaking R-1 zoning is step one.

step one to banning single family housing.

@prk166

What part of my comment do you think is a false claim?

“Banning single family zoning does not ban the building of single family houses.” is not false.

Do you not believe that banning single family zoning supports free market principles?

If it was the real free market, developers would be allowed to build all single family homes or all high density or mixed single family homes and high density in their developments. And their customers or buyers would decide if they made the correct decision or not, by buying the properties or not..

As if suburban sprawl was a free market! Do you have a toll road to get to your house in your subdivision, prk166?

Jane shows herself to be the cunty troll she is by going full on whataboutism and attacking a strawman. Hopefully her lady parts don’t smell as bad as the shit she’s flinging here.

Ted, I’m buying the lot next to you and buying a 10 story apartment building.

*building

Not happening because I don’t live in the UGB.

Sketter says, “Banning single family zoning does not ban the building of single family houses.”

If there is no land to build single-family houses, then no more will be built. The land inside SFBay Area UBGs is completely built out. There is no room for more homes. That’s why they want to tear down SF homes to build apartments.

Besides, the issue is not the right to live in a SF home but the right to live in a SF neighborhood.

In Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement the AP can’t even refute the statement that “banning single family zoning doesn’t ban single family housing development”. Who is “they” is that the government or private developers? If it’s private developers then are building what the market demands, which sounds very free market to me. Once again AP is all for free market principals when it comes to sprawl, as long as it’s single family zoning, but not when it comes to reducing zoning regulations for current zoning regulations.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Graham%27s_Hierarchy_of_Disagreement.svg

“If it’s private developers then are building what the market demands, which sounds very free market to me.”

Only if you don’t understand the free market. A free market is an economic system where supply and demand are free from any government intervention.

The mere existence of government price fixing (wage floors–minimum wage; the price of money–interest rates) show that there isn’t a free market. Add the countless pages of land-use regulation and all type of other regulations. Private developers are building what a HIGHLY REGULATED AND DISTORTED MARKET demands. Anyone with two brain cells to rub together would not describe current housing development as a free market.

@ted if AP is all for free markets then why does he ONLY advocate for single family zoning when it comes to urban sprawl?

Please read the stretches carefully and don’t make false assertions that the AP only advocates for single family zoning.

Read Randal’s central claim and let it sink in; if you still don’t get it, it’s because you just can’t get it:

“Zoning land as a substitute for deed restrictions and then yanking away that zoning betrays the homeowners in such neighborhoods.”

Urban sprawl is a myth, It is free people freely choosing to live in a low density area.

”

@ted if AP is all for free markets then why does he ONLY advocate for single family zoning when it comes to urban sprawl?

”

Sketter, even your mom finds your ignorance revolting.

”

@ted if AP is all for free markets then why does he ONLY advocate for single family zoning when it comes to urban sprawl?

”

Sketter, even your mom finds your ignorance revolting.