In 2012, the Charlotte Area Transit System (CATS) proposed to operate commuter trains between uptown Charlotte and the suburb of Mount Mourne. In 2011, it predicted (based on 2009 prices) that start-up costs for the 25-mile Red Line route would be about $452 million, slightly more than the cost of Charlotte’s first light-rail line (which was $444 million). While the commuter-rail route was almost three times as long as Charlotte’s first light-rail line, it was projected to carry fewer than a third as many riders: 5,600 per day as opposed to 18,100 per day.

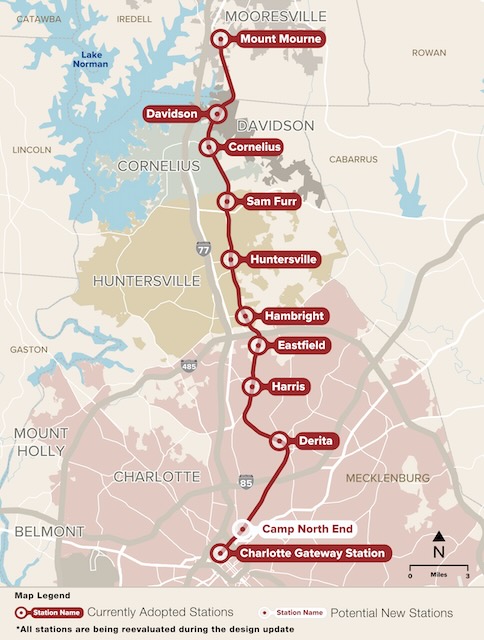

Map of proposed Red Line commuter train.

Map of proposed Red Line commuter train.

Due to the high cost and small number of riders, the Federal Transit Administration refused to provide any federal funding for the project. At the time, the FTA’s cost-effectiveness rule limited federal funding to projects that cost less than about $25 per hour saved by transportation users, and the commuter train wasn’t projected to save enough hours to get the cost below this threshold.

Instead of viewing this as a signal that the Red Line was a bad idea, CATS proposed that communities along the line share half the cost of the line (which is approximately the amount that the federal government might have covered), while the state of North Carolina would pay 25 percent and CATS would pay the remaining 25 percent out of general sales tax revenues. While at least some of the seven communities expressed reluctance about paying that much money for so little benefit (one of them even hired me to review the plan), what ultimately killed the idea was that Norfolk Southern, which owned the tracks the trains were to run on, refused to allow passenger trains on its property.

That roadblock was removed last month when the city of Charlotte bought the rail line from Norfolk Southern for $74 million. Undeterred by the fact that neither the federal government nor suburban cities think the project makes any sense, the city wants to increase sales taxes on everyone in the region to pay for the commuter-rail line that will serve only a few thousand riders in one corridor.

Information that the city has handed out to the public touts the benefits of a commuter-rail line without saying anything about the costs. Those benefits supposedly include economic development and transportation equity.

In fact, transportation equity is an excellent reason to oppose this project. Recent census data estimate that the median family income in the Charlotte urban area is $104,000, yet the median family income of suburbs that would be served by this rail line ranges from $134,000 to $182,000. Asking median taxpayers to pay a regressive sales tax to fund expensive rides to a small number of high-income people is the very definition of inequity.

If Charlotte really wanted to help low-income people, it would spend more money on highways and give up spending money on transit improvements. According to the American Community Survey, Charlotte-area workers earning under $25,000 a year were more likely to drive alone to work than workers in any income category earning more than $25,000 a year. The 3,800 low-income (under $25,000 a year) workers who commuted by transit were vastly outnumbered by the more than 114,000 low-income commuters who relied on automobiles. Since working-class people are less likely to be able to work remotely or have flex-time hours, they are more likely to be stuck in traffic, and efforts to relieve congestion will do more to help them than expensive transit projects that mainly serve high-income communities.

Nor is the line likely to spur any economic development. New economic development along most light-rail lines, including those in Charlotte, has often if not always been subsidized using tax-increment financing (TIF). Without TIF, much of that new development would not have taken place, or at least not along the rail lines. TIF is a burden on other taxpayers because the taxes on new developments that would have funded schools, fire protection, police, and other services would go to subsidize the developments instead, leaving taxpayers in the rest of the region to either accept a lower level of services or pay more taxes to fund those services to the subsidized developments.

Since commuter rail would carry far fewer riders than light rail, it would be even less likely than light rail to generate any unsubsidized economic development. Any subsidies to such development would simply be another burden on local taxpayers.

In 2019, CATS revised its cost estimates upwards and ridership estimates downwards. It added $21 million (about 5 percent) to the costs to account for inflation and another $37 million due to a change in alignment. Meanwhile, it reduced estimated ridership to just 1,772 riders per weekday in the opening year, eventually rising to 2,963 weekday riders in 2045. Those are such small ridership numbers it is amazing that anyone thinks this is a worthwhile project.

The cost estimate is totally unrealistic. The 5 percent inflation factor is seriously inadequate considering that the consumer price index grew by 19 percent between 2009 and 2019. Moreover, construction costs grow at different rates from consumer prices. According to the Federal Highway Administration, highway construction costs have grew by 40 percent between 2009 and 2019, and it is likely that transit construction costs have grown by at least the same amount.

Transit estimates made in 2019 completely ignore the major changes in transportation patterns that followed the pandemic. According to the American Community Survey, the share of workers in the Charlotte urban area who work at home increased from just under 10 percent in 2019 to 27 percent in 2023, which is one of the highest in the nation. This drove down the share of workers taking transit to work from 2.4 percent in 2019 to 1.5 percent in 2023.

While transit shares may have increased slightly in 2024, they haven’t increased much. As of August 2024, Charlotte transit was carrying only 65 percent as many riders as in 2019. Worse, Charlotte’s commuter buses, which serve the same clientele as would be served by a commuter train, were carrying only 37 percent as many riders as in 2019. The reason, of course, is that people who worked in downtown (which is called uptown in Charlotte) before the pandemic were among those most likely to work at home at least some days a week after the pandemic. This had a severe impact on transit lines that go uptown, as the Red Line would.

The main question is whether the 1,772 opening year weekday ridership should be reduced by 35 percent, which is the current ridership of all Charlotte transit compared with 2019, or 63 percent, which is the reduction in Charlotte’s commuter-bus ridership. Even if it is just 35 percent, that puts opening year ridership at only 1,152 per weekday, eventually rising to 1,926 riders in 2045. Considering that the average ratio of annual commuter-rail trips to weekday trips was 311 in 2022, this represents 358,000 annual riders in an opening year of 2030 and 599,000 annual riders in 2045.

Also ignored by the 2019 estimates is the effects of the pandemic on construction costs, which have grown dramatically due to supply-chain problems and labor shortages. Federal Highway Administration estimates indicate construction costs grew by more than 60 percent between 2019 and 2023, and by 125 percent between 2009 and 2023. This means Red Line construction is likely to cost well over a billion dollars.

Operating costs have also increased. CATS’ 2011 estimates projected that the Red Line would cost $13 million a year to operate in its opening year (which was supposed to be 2018), rising at a rate of 4.7 percent per year after that. By an opening year of around 2030, the annual cost would be about $22.5 million, which is nearly $63 per rider. By 2045, the annual cost would be $45 million or about $75 per rider. Even without considering capital costs, these costs are outlandish considering that in 2019 CATS spent $4.45 per rider operating its light rail and $6.20 per rider operating buses.

To pay for this line as well as other transportation projects, the city of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County want to ask voters to approve a 1¢ sales tax increase that would generate $19 billion over 30 years. While Charlotte-area voters will have an opportunity to reject this plan, since the Red Line is only a small part of it, commuter rail will not get a decent public debate.

Now that Charlotte has already spent $74 million buying the rail line, if voters approve the sales tax neither the city nor CATS will bother to seriously consider cost effectiveness or whether commuter buses can do the same work for a lot less money. To do so would be an admission that the original $74 million expense was a complete waste.

In sum, CATS and the city of Charlotte are greatly overestimating Red Line ridership while underestimating its costs. The federal government considered the Red Line to not be cost effective even at the higher ridership numbers and lower costs. It is certainly not cost-effective in a post-pandemic world where construction costs are much higher and large numbers of people are working at home instead of riding transit. This is just one more demonstration of how easy it is to use the power of government to spend other peoples’ money on stupid things.

Total spending on transit in 2023 was close to 80 Billion dollars

Total Road spending was around 200 Billion.

Except Transit accounted less than 1% modal share transportation usage in 2019 by 2023 was down to 0.05%?

Transit gets 1/3 nations transport dollars to move less 1/200th nations passenger volume, subtract NYC/NJ/Long Island area it’s 1/400th it’s literally cheaper to bus them in rolls royces

It was never about providing transportation it was about providing jobs for well connected contractors (and union thugs with corrupt ties) and trying to turn their downtowns into Big city style heavy real estate investments.

Even worse, there is a bill to allow Amtrak to sue hardworking freight train operating companies that barely scrape by, so that a few privileged riders can zip around the country without a care in the world!

https://x.com/fairyartmother/status/1845537871387676783