Last month, anti-automobile activists led by the Congress for the New Urbanism announced the formation of a national Freeway Fighters Network. The network opposes new freeways and freeway expansions and wants to shift freeway money to other forms of transportation. Among other things, they object to new freeway capacity because it induces more highway travel.

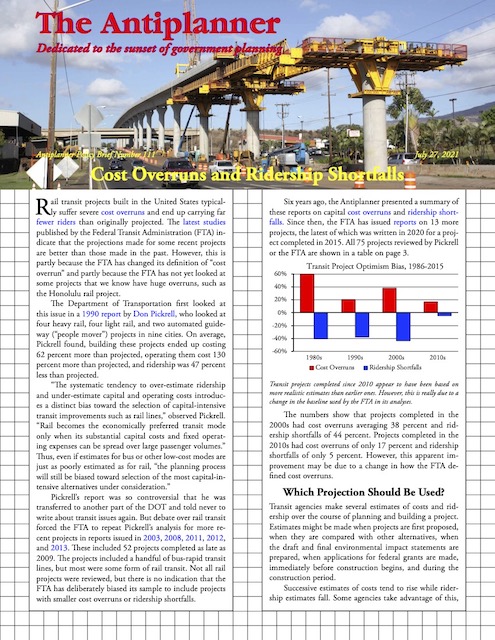

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

Click image to download a four-page PDF of this policy brief.

I have a message for these anti-auto activists: The war on the automobile is over. The automobile won. More accurately, auto drivers and users won. It is time for those engaged in this war to stop wasting their time, and everyone else’s, and start doing something productive. People concerned about the impacts of the automobile should give up trying to reduce driving, which has never worked, and instead encourage new automobiles and highways that are safer, cleaner, and more energy efficient.