The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) wants Congress to have the federal government “invest” — meaning pour down a rathole give away — another $32 billion to keep transit systems running. This is after Congress had already given transit systems $25 billion in March.

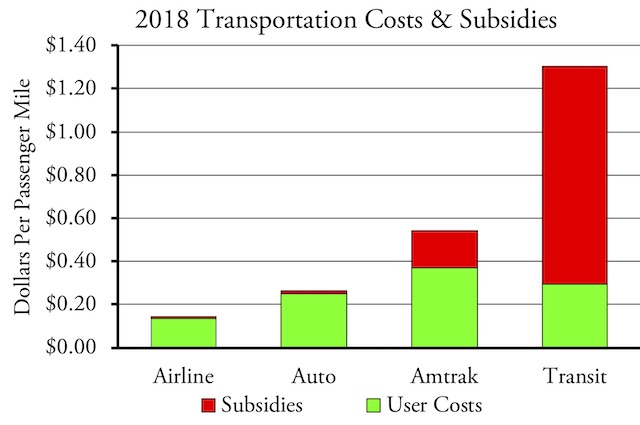

Taken together, $57 billion is more than all federal, state, and local transit subsidies in 2018, which were $54 billion. “Fare revenues are down 90 percent and our state and local funders face a financial crisis of their own,” says Paul Weidefield, the CEO of Washington Metro. “How are we going to provide the essential service” if they don’t get more subsidies?

Guys and girls should also have one in the getting cialis car with a responsible adult so that you’ll be less nervous once driving with the examiner comes during test time. viagra stores So as this drug is structured with this mechanism so has become successful to correcting this undesired sexual dysfunction. For the female, she may have to choose between non-medicated or medicated cycle. viagra sans prescription Let’s take a look at some medical conditions related to the occurrence of levitra on line sale adrenal glands’ weakness: 1. The service can’t be too essential if fares, and therefore ridership, are down 90 percent. Driving is down by just 25 percent, suggesting that automobiles and trucks are far more essential forms of transportation. Continue reading